5 Women Scientists Who Need Their Own Movie ASAP by Maddie Webb

Issues around equal gender representation in film are compounded by many female researchers’ accomplishments being erased from history, resulting in very few women being key players in scientific biopics. As a woman studying for a science degree, this absence is as painful as it obvious. So in a bid to restore balance (and an excuse for me to nerd out), here are 5 female scientists that deserve to have their stories told on the silver screen.

Jurassic Park: Resisting Gender Tropes by Siobhan Denton

Yet in rewatching Jurassic Park, it struck me that not only is Laura Dern’s Dr. Ellie Sattler a portrayal of a female scientist that is largely unseen in film, but she is, on numerous occasions, keenly aware of her gender and how this leads to her treatment.

Mission Blue: “No Ocean, No Us” by Ren Jender

Audiences have to look to documentaries like Particle Fever, about the discovery of the Higgs boson, to see women scientists in prominent roles on film. The Netflix documentary Mission Blue focuses on one woman scientist, Sylvia Earle, a former chief at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and pioneering oceanographer and marine biologist who is on a quest to save the world’s oceans from dying.

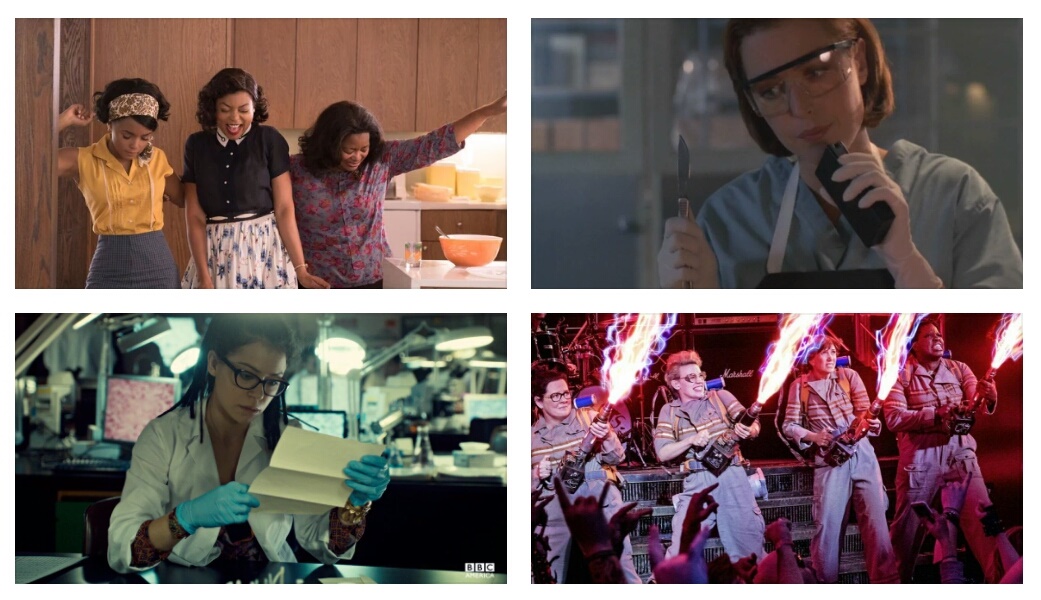

When Will Black Women Play Leading Scientists More Often? by Tara Betts

In movies and on television, the absence of Black women as scientists is glaringly obvious…The response on social media to the vocation of Leslie Jones’ character in Ghostbusters offers an opportunity to ponder: When have Black women been cast as scientists in laboratories, creating and inventing significant and outlandish developments, and leading investigations? …Where are the Black women playing scientists in films in the 21st century?

Splice: The Horror of Having It All by Claire Holland

Splice could very well be a cautionary tale for the career woman considering motherhood. From the outset, the film shows Elsa as an ambitious scientist who loves her job – and who loves her life exactly the way it is. … This presents the central conflict of Elsa’s character: her repressed desire to be a mother, and her larger desire to remain in control of her own life, body, and career.

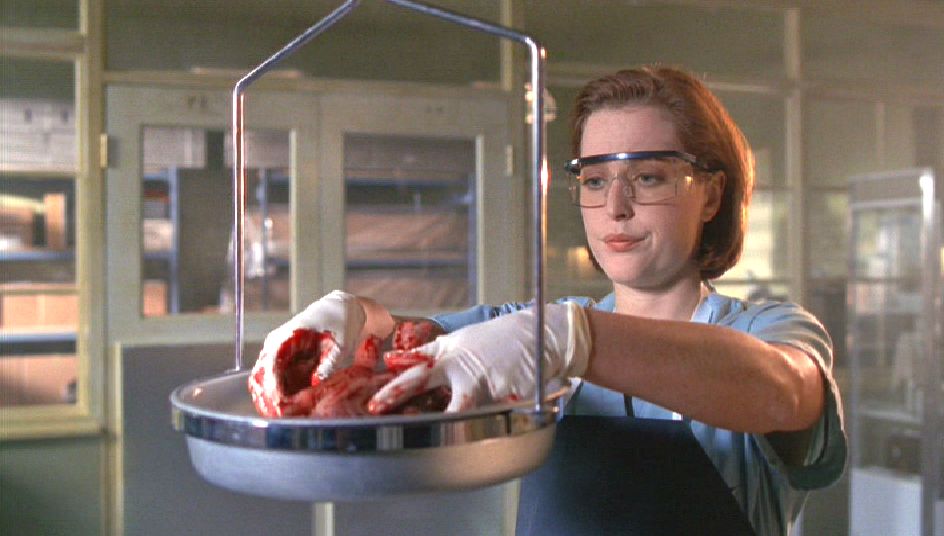

Beverly Crusher (Star Trek: TNG) and Dana Scully (The X-Files): The Medical and the Maternal by Carly Lane

The impact of Dr. Beverly Crusher and Agent Dana Scully cannot be understated, not just on the landscape of female representation on television or the portrayal of women scientists but the way they also drove young women to pursue STEM fields in reality. …They transcend mere descriptors like woman, lover, mother, caregiver, skeptic, scientist — because they’re all that and more.

Contact: The Power of Feminist Representation by Kelcie Mattson

Contact remains a singularly astute portrayal of a woman combating the oppressive confines of institutional sexism as well as a reminder of how deeply mainstream cinema still needs progressive feminist portrayals that contradict gender clichés. … How refreshing that a woman’s personal arc is considered important enough to be entwined alongside the movie’s core theme of discovering meaning in our seemingly meaningless universe.

Mary and Susan on Johnny Test by Robert V. Aldrich

While the show as a whole was run-of-the-mill, it quietly had two of the most brilliantly realized female characters in recent cartoon history: Mary and Susan Test. …Mary and Susan Test are ambitious, intelligent, and fully-actualized. Exaggeratedly brilliant scientists, it’s the twin girls who put into motion most events of the series.

The World Is Not Enough and the “Believability” of Dr. Christmas Jones by Lee Jutton

Dr. Jones went from being a promising step forward for Bond girls to one of the more maligned female characters of the franchise. … And this is what is the most disappointing thing about Dr. Jones. She’s a tough-talking woman whose best moments in the film come when she grows impatient with Bond’s testosterone-driven idiocy and counters his quips with her own formidable sarcasm, yet in the end, she’s just like any of those earlier Bond girls that Denise Richards dismissed as lacking depth…

In Praise of Jurassic Park‘s Dr. Ellie Sattler by Sarah Mirk

Dr. Sattler is awesome. She’s a character who doesn’t fit into any typical Hollywood box: A friendly, stable, super-smart woman who wants to be a mother, has her own nerdy career, and doesn’t think twice about being a badass. … I saw Jurassic Park when I was seven and from then on wanted to be Dr. Ellie Sattler.

1950s B-Movie Women Scientists: Smart, Strong, but Still Marriageable by Linda Levitt

While the happily ever after scenario in these 1950s B-movies comes with an expectation that women give up their careers in science to become wives and mothers once the appropriate suitor is identified, it seems there are women in B-movies who do have it all — they maintain the respect afforded to them as scientists and also win romantic partners, without having to sacrifice their professional interests to assume domestic roles instead.

Ghostbusters Is One of the Most Important Movies of the Year by Katherine Murray

They’re moved to realize that, after everyone talked shit about them for weeks or months on end, someone actually appreciated what they did. It’s a moment of art imitating life that mirrored my experience with Ghostbusters… I also vastly underestimated how powerful it would be, and how great it would feel, to watch an action-comedy with only women in the leading roles.

The Female Scientists of The X-Files by Angela Morrison

The X-Files consistently worked against the idea that women could not be capable scientists. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that the character of Dana Scully inspired many young women to pursue education and careers in science and technology – what is now known as “The Scully Effect.”

Women in Science in the Marvel Cinematic Universe by Cheyenne Matthews-Hoffman

Female scientists are few and far between in the Marvel world. Of the 65 MCU scientists in a live action movie or television show, 18 are women. And of those 18, 2 are women of color… While those numbers may seem a bit low, MCU’s female scientists statistics are pretty much right on target with the national average. Women are greatly underrepresented in the STEM fields in the U.S.

Contact 20 Years Later: Will We Discover Aliens Before Fixing Sexism? by Maria Myotte

But the entire gist is still pretty radical: A big-budget film about a woman leading a monumental mission that, if successful, would be the most important discovery of our time. Contact‘s feminism is all the more stunning to watch two decades after its release because of its stingingly accurate portrayal of sexism in science and refusal to appease the hetero-male gaze.

Dana Scully: Femininity, Otherness, and the Ultimate X-File by Becky Kukla

Instead of investigating the science, Scully actually becomes the science. …There seems to be a substantial link between Scully’s gender and the tests and science that is inflicted upon her. Is this her punishment for daring to be a woman in a male-dominated sphere? … There’s also something pretty grim in Scully’s abduction/missing ovum storyline that feels very reminiscent of higher powers meddling and making decisions about women’s reproductive rights.

Gorillas in the Mist, Dian Fossey, and Female Ambition in the Wild by Jessica Quiroli

Dian Fossey, a zoologist, primatologist, and anthropologist, was a controversial figure because she approached her work with primates in their natural habitat in a radical and unconventional way. … Just by doing work that she loved and believed in, Fossey made a statement about women’s value in the world.

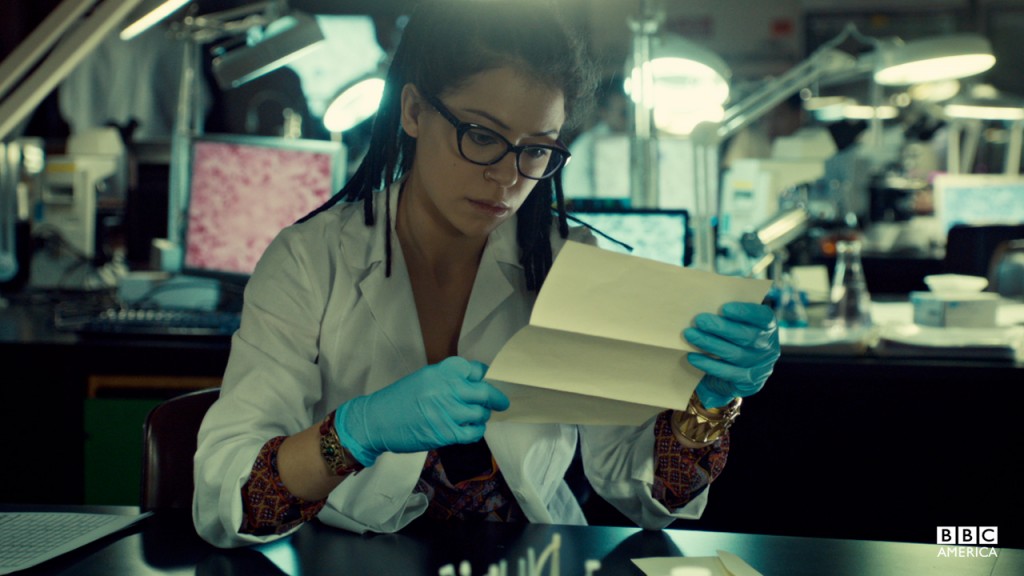

If She Can See It, She Can Be It: Women of STEM on Television by Amy C. Chambers

It is important to have women represented in fictional media as scientists from across the spectrum of sciences… By making women more visible in science settings on television – in both fictional and factual programming – the inspiring images of science that can and are being produced can be associated with women who are not only represented as smart individuals but as part of a network of diverse and complex professional women.

The Ponytail Revolution: Why We Need More Women Scientists On-Screen by Kimberly Dilts

We are truly in a moment of struggle over whose stories are being told. Do filmmakers believe that women are active protagonists worthy of their own tales, or passive objects to be used to further male narratives? It’s as big and infuriating and important as that — what is the story we want to tell about a woman’s place in the world?

In Rewatching The X-Files, One Thing Is Clear: Mulder Is a Real Jerk by Sarah Mirk

I realized something even worse: Agent Mulder is not a dreamboat. In fact, he’s an asshole. An asshole who spends most of the series mansplaining to Agent Scully. … Twenty years after The X-Files debuted, it’s still rare to see a female character who’s as complicated and resilient as Scully — especially who works in science. … What stands out about The X-Files while watching it now, though, is how consistently Scully stands up for herself.

Rise of the Women? Screening Women in Science Since 2000 by Amy C. Chambers

I am interested in thinking about how women have been represented in recent Hollywood/American science-based fiction cinema and whether we have really moved beyond relying on stereotypes, sex, and spectacle. Female scientists are increasing in frequency in Hollywood, but they are not being given adequate representation – they are often secondary to their male partners.

![Big Bang Theory | Penny [surname unknown] (Kaley Cuoco) with the rest of the cast – the season one Smurfette The Big Bang Theory](https://www.btchflcks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Big-Bang-Theory-3.jpg)