This guest post by Deborah Pless appears as part of our theme week on Dystopias.

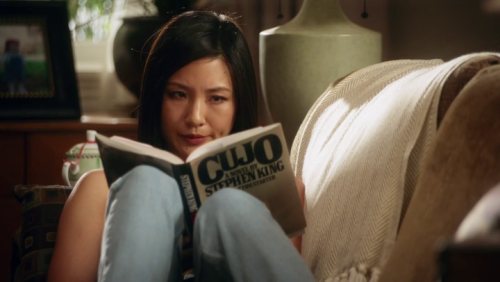

The first scene of The 100 makes it pretty freaking clear that this is a show about dystopia. We are introduced to a pretty blonde girl drawing a landscape scene using only the dirt and grime of her prison cell. The voiceover narration informs us that this picture, and all of the other pictures that ornament her solitary confinement, is drawn from imagination. She has never set foot on Earth, and she will almost certainly die in space like all the rest of her people.

Cheerful stuff, huh?

The girl, Clarke Griffin (played by Eliza Taylor), is our main character and the voice of reason in The 100, a CW show that came on as a midseason replacement last year to middling reviews, but has continued to improve and now, after the completion of its second season, officially qualifies as a “cult hit.” Based on the novel series of the same name by Kass Morgan, you would be forgiven for assuming this is just another Hunger Games ripoff. It isn’t.

The 100 is a show ostensibly about teenagers falling in love and making poor choices against the backdrop of an ever-changing dystopian landscape, but in reality the show is far less concerned with emotions than with social commentary. The dramas and frivolities of the first few episodes fade away as the show goes on, being replaced instead by a compelling and gripping drama about political power, the ethics of war, medical experimentation, torture, the values of indigenous cultures, imperialism, and, occasionally, hope for the future.

It is also unquestionably a show about dystopia. Though evident in the first scene, it wasn’t until well into the second season that I realized that the show wasn’t just an exploration of one particular dystopian future, however, but instead an exploration of all of them. Really. All of them. Every organized culture or civilization that our heroes encounter in the course of the series is a different exploration of dystopia. And while this can make the show rather bleak and hard to watch, it’s fascinating.

The basic premise of the show is inherently dystopian. Our heroes all live on the “Ark,” a cobbled together mush of space stations in orbit over the Earth. They’ve lived there for 97 years, since a nuclear war wiped out all life on Earth. The people of the Ark know that they are just a waiting generation who will live and die on the Ark with the understanding that in another hundred years their descendants will be able to go down and live on the planet once the radiation levels have decreased.

Because they have limited supplies, the Ark is run as a totalitarian dystopia. There is never enough food, water, air, or medicine. All food is rationed, all parents may have only one child, and medicine is reserved only for cases when the alternative is death. Even their shoes and underwear are handed down from one generation to the next. Break a law on the Ark – and there are many – and you die. No trial, no reprieve, just a sad farewell to your loved ones, the removal of all shoes and useful clothing, and then a swift death being shot out the airlock.

If a minor commits a crime, then they are sent to the “SkyBox,” a holding detention center where they await turning 18. Once 18, they face a panel, and that panel will decide if they should be “floated” or returned to the Ark’s main population.

Our story starts when Clarke and her fellow inmates in the SkyBox are hustled out of their cells and onto a dropship. Confused and terrified about what is happening, the teenagers (and children) soon realize that they are going down to Earth. Why? Well, as they and we learn, because the Ark can no longer support life and they must find out if the Earth has healed enough to sustain them. In other words, Clarke and all of her friends, 100 of the most vulnerable members of this society, are used as canaries in a coal mine.

So obviously the Ark is a dystopian place. As the show goes on – obviously the kids survive their trip to the Earth’s surface – it become increasingly clear that the governmental situation on the Ark is hellish at best. One child was incarcerated for hitting the guards who held her back as her parents were executed. Another character, Octavia (Marie Avgeropoulos), committed no crime but being born. As she has an older brother, her birth was unauthorized and when she was discovered she was sent directly to the SkyBox. And so on. While some of the crimes are legitimate, many are the result of children growing up in a totalitarian state. So clearly it’s going to be better here on the ground, right?

Ha!

As the kids quickly learn, the ground is no more hospitable than the Ark was. While there is no totalitarian rule, their society quickly devolves in a Lord of the Flies situation. A hundred teenagers and children who have been locked up in prison and forced to live in a police state their whole lives suddenly have complete freedom? Yeah, it goes pretty Lord of the Flies. Then, just when they’re starting to get their act together, it becomes clear that the Ark children are not the only ones alive on the ground. There are others.

That brings us to the Grounders, as the people of the Ark come to know them. The Grounders represent another form of dystopia, this one more similar to Mad Max. The Grounders are the humans who developed an immunity to the radiation poisoning the Earth and so rebuilt society.

They hunt with bows and arrows and spears, wear an amalgamation of clothes they found and animal leathers, paint their faces to look scarier, and even speak a completely different language. Heck, they even have a village called “ton DC” built in the bombed out ruins of Washington DC. In other words, they appear at first to the Ark kids as “savages,” a dystopian view of who they could become if they lose all of their “civilization.”

Fortunately, the truth turns out to be much more complicated than that. While the Grounders are genuinely savage, they also have an artistic and healing tradition that is complex and beautiful, as well as a culture that is distinct and clearly quite functional. Though tribal and very divided by factions, the Grounders quickly become the least dystopian society on the show, and the Ark kids even cease their war and try to make a truce.

Unfortunately for our heroes, though, the Grounders are the least of their problems. As the story progresses, the kids run into another dystopian hellscape, this one called “Mount Weather.” Mount Weather is a bunker, or system of bunkers, hidden inside a mountain and home to a large population of seemingly nice, decent people. They’ve lived inside the mountain, sheltered by its radiation shields, for the past hundred years. They have abundant food, shelter and safety, and even flourishing art and culture. It’s the first place the kids go that is, well, beautiful.

But that beauty covers over the horrible truth that Mount Weather is just another dystopia. This time it’s a medical one, where the people of Mount Weather are basically vampires, kidnapping Grounders and draining them of their blood in the hopes of building up a radiation immunity. When the scientists at the mountain discover that the Ark kids have an even better immunity, they decide to harvest the kids’ bone marrow, whether they consent or not.

Not to be outdone, by this time the bulk of the Ark’s population has reached the ground and formed a camp called “Camp Jaha,” which operates under the same dystopian rule as the Ark did. And across the mountains we discover a desert wasteland of outcasts and landmines and pilgrims searching for the “City of Light.” That City of Light? Turns out to be just another terrifying technological dystopia.

What’s the point of all of this? Well, aside from the writers of The 100 clearly enjoying the bleakness of their world, these competing dystopian futures actually manage to form a cohesive picture not of dystopia but of how we ought to respond to it.

Like I said above, our main character for the show is Clarke. Clarke is smart, caring, incredibly pragmatic and kind of scary. She quickly becomes the leader of the kids she came down with, but goes on to become the leader of all of the people of the Ark, a symbol of resistance for Mount Weather, and more. While there are other characters whose lives we follow, the story revolves around Clarke, particularly around how Clarke reacts to dystopian societies. Namely, how she never reacts well.

On the Ark, Clarke was locked up in solitary confinement for the crime of treason. She and her father discovered that the life support of the station was failing and tried to warn everyone. He was executed; she was locked up. At the dropship, when the kids go all Lord of the Flies, Clarke is the voice of reason, foraging for food and medicine while the others let the world burn.

When captured by the Grounders, she resorts to diplomacy. When captured by Mount Weather, she speaks out against their propaganda and escapes, taking a former enemy with her. She quickly establishes herself as the real power of Camp Jaha and, with the help of her friends, brokers a deal with the Grounders to go to war against Mount Weather. Not bad for a 17-year-old girl. Not bad for anyone.

Clarke clearly believes in the values of a good society, but what makes her a fantastic character is how strongly she believes in speaking out against a bad one. She has no qualms about speaking truth to power. And she will not abide a dystopia. By showing Clarke butting heads with so many different kinds of failed societies, we’re given a look at what it means to stand up for our own rights and the rights of others in any situation. I’m not saying that the show is perfect or completely unproblematic, but I do think that it has something very interesting to say when it comes to how we ought to react to dystopian landscapes.

It says that we should react with understanding. We should figure out what’s wrong, what about the society is making it so unbearable, and then seek to fix that. Clarke doesn’t believe necessarily in blowing up bad societies, though she does sometimes do that. Literally. It’s more that her arc is about seeking the good and using these visions of failed places to figure out what will work and what should be.

This is especially meaningful considering that Clarke is, well, a teenage girl. She’s the demographic of our society that we pay the least attention to and give the least credence. And yet the whole show is centered around proving how much value Clarke and the other kids that society originally deemed expendable actually have.

It’s not just Clarke, either. The show centers on the kids the Ark sent down, the ones society had abandoned, as they explore different kinds of dystopias. They’re a pretty diverse bunch and their reactions to these different situations give us a wealth of commentary on those dystopias.

So while Clarke’s not perfect and neither is the show, they’re clearly trying. Clarke sometimes falls into white savior behavior, and the show occasionally tries to force storylines that feel disingenuous and frankly kind of weird. But whatever. I don’t need a perfect show or a perfect heroine. I’d rather have this, a meta-commentary on the different types of futures we envision for ourselves as a species. Even better, it’s a meta-commentary where each future is torn down and reassembled by the children who will actually inherit it.

As The 100 shows us, the point of dystopia isn’t to look at the future and weep. The point of dystopian landscapes is to give us a vision of what our future could be and then to explore how to make sure it never is.

Deborah Pless runs Kiss My Wonder Woman and works as a freelance writer and editor when she’s not busy camping out at the movies or watching too much TV. You can follow her on Twitter and Tumblr just as long as you like feminist rants, an obsession with superheroes, and the search for gluten-free baked goods.