The Conjuring: When Motherhood Meets Demonic Possession by Caroline Madden

Punishment is the main objective of the demon Bathsheba in The Conjuring, and specifically she seeks to punish the mother figure of a family. The hauntings and road to possession begin when in 1971, Roger and Carolyn Perron move into an old farmhouse in Rhode Island with their five daughters. Slowly, they begin to experience paranormal disturbances.

Because Being Female is Frightening Enough: #YesAllWomen and The Exorcism of Emily Rose by Rebecca Willoughby

In the film a young girl, Emily Rose, perishes following a protracted period of “attack” by demons while under the protective care of Father Moore, a Catholic priest. Female attorney Erin Bruner is chosen to defend Moore against charges of negligent homicide in Emily’s death. Through the two’s connection to the girl throughout the film, each undergoes what I’ve called here a “conversion experience,” as they learn more about the possibility that demons really do exist—demons that can be read to correspond to the challenges that women face in culture every day. Even before the advent of #YesAllWomen, a film like The Exorcism of Emily Rose shows us how to overcome skepticism and create a connected community of individuals committed to sharing troublesome experiences in the service of awareness and activism.

Demons: Finding New Language for an Old Cult Classic by Lisa Bolekaja

I am a horror fan and most times I root for the monster. There, I said it. I root for what should be the feared. The dreaded Other. With all the loaded symbolism that the horror genre represents (fear of sex, fear of the unknown, fear of death and decay, xenophobia etc), I find it cathartic and often liberating to root for the disruption of life as we know it. I love watching humans deal with chaotic change.

Twin Peaks Mysticism Won’t Save You From the Patriarchy by Rhianna Shaheen

I do believe that Lynch and Frost meant to use BOB as “the evil that men do” and as a means to understand family violence and abuse, but they jump around the issue so much that it only reflects uncertainty. The show’s inability to hold evil men responsible for their actions is too reminiscent of our own society. As soon as we answer “Who Killed Laura Palmer?” the show does its best to rebury the ugly truth that we so struggled to uncover. After that it fully commits to understanding the mythos behind it. This is troubling to me.

The Strangeness of (Surrogate) Motherhood in The Innocents by Ren Jender

Part of what makes the excellent 1961 film The Innocents different is the main character, the governess, Miss Giddens (played by Deborah Kerr), is thrust into a parental role suddenly. We see her at the beginning in an interview with the children’s uncle, a handsome playboy (played by Michael Redgrave, Vanessa’s father) who tells her he spends much of his time traveling and the rest in his home in London. When he offers her the job at his country estate, he takes her hand (a bold move for the Victorian era, when the film takes place) and asks if she is ready to take full responsibility for the children, because he doesn’t want to be disturbed during his adventures in London and abroad.

Direct from Hell: Paranormal Activity and the Demonic Gaze by Alexandra West

Micah’s patriarchal control through the first half of the film is omnipresent as he mocks, coerces and films his girlfriend’s descent into possession. The second half of the film deals with the demon taking control of the film. Micah and Katie are too weak to properly deal with the situation and they lose sight of their safety. The audience see what the demon wants them to see; it is in control of not only Katie’s mind and body, but also what the audience is exposed to, creating an unstable and terrifying experience.

She’s Possessed, Baby, Possessed! by Scarlett Harris

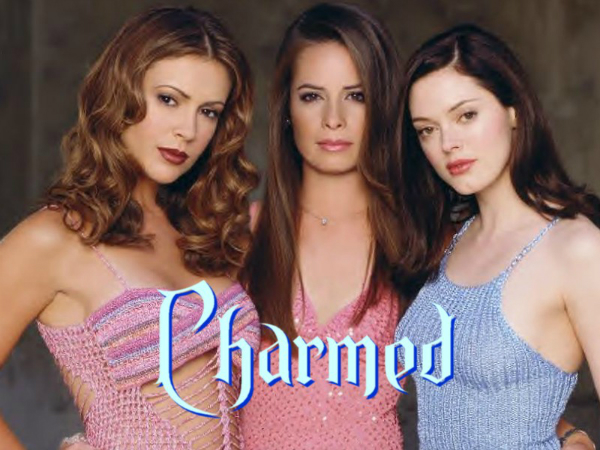

When Phoebe is taken over by the deadly sin lust in “Sin Francisco,” she sexually assaults her professor and has sex with a policeman on the job, while Piper dances on her bar during her high school reunion when she’s possessed by an evil spirit. And almost all the evil women in the show are sexualized: the succubus, shapeshifter Kaia, the Stillman sisters in “The Power of Three Blondes,” the seer Kyra, etc.

Does Jennifer’s Body Turn The Possession Genre On Its Head? by Gaayathri Nair

Jennifer’s Body is not a traditional female possession film. The genre is generally typified by mild mannered asexual women who begin to act in overt and sometimes pathologized sexual ways once they become possessed. Jennifer’s sexuality, on the other hand is firmly established at the beginning of the film, from her clothing, the way she interacts with both her best friend Needy and the males in her school, to where she casually mentions that she is “not even a back door virgin anymore.”

The Shining: Demon Selection by Wolf

Jack is both a victim and perpetrator of domestic violence. Jack’s father was an abusive alcoholic who beat and berated him. When Jack drank he used to parrot his father’s words (“take your medicine” “you damn pup”). He is primarily verbally abusive. The last incident of drinking that pushed him to sober up was accidentally breaking Danny’s arm. Wendy, perhaps like Jack’s mother, lied for him but swore she would leave if he didn’t sober up.

The Notion of “Forever and Ever and Ever” in The Amityville Horror and The Shining by Rachel Wortherley

The nightmare that Jack and George share signifies their innate fear—the possibility of destroying the family they, as men, have built.

Rosemary’s Baby: Who Possesses the Pregnant Woman’s Body? by Sarah Smyth

To what extent does a woman, pregnant or otherwise, “own” her body? To what extent can or should a woman’s (pregnant) body be subject to social concerns? Physically and socially, where is the divide between the mother’s body and the baby’s body? By raising these questions, Rosemary’s Baby is not only concerned with the spiritual but, also, the social possession of the female body.

Jennifer’s Body: The Sexuality of Female Possession and How the Devil Didn’t Need to Make Her Do It by Shay Revolver

And now Anita is “needy” no more because she has tasted the power, lived to tell the tale and will use her new demon passenger to right the wrongs that she sees fit. Even though she’s possessed, you can sense that she will guide herself and the demon within and take control of it. Freedom is a beautiful thing, even if you have to be possessed to make it happen.

The Invocation of Inner Demons in Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession by Giselle Defares

Mark’s doppelgänger reflects Anna’s fascination with Heinrich’s persona: narcissism, religion, imagination, and his sexual freedom. Anna’s doppelgänger, Helen, is a pure, calm, and collected woman. That’s precisely what Mark wants–the opposite of Anna.