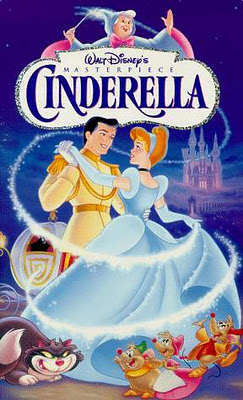

Disney. The word is so synonymous in my mind with “animated feature films” that it’s like using “Kleenex” for “tissue.” When children come to my house, as they sometimes do, they’re invariably drawn to my huge selection of “Disney movies,” only about 70% of which are actually affiliated with Disney in any way shape or form. I enjoy most of them, or I wouldn’t own them. They each have their own problems, but a good many of them have something truly positive that I treasure. And what better way to start a deconstruction of animated feature films with the one I knew first and loved best: The Little Mermaid?

The Little Mermaid is possibly one of the most contentious movies I’ve ever loved. It was created in 1989, and has been specially beloved by many children in general and by myself in particular since then. I must have watched the movie eighty squintillion times as a child; it was one of the few videos I loved enough to manage to convince my parents to buy, and I watched it until the video literally broke from use. By that point, Disney had locked the reel in their “appreciate for value” vault and when they relaunched the movie in theaters in 1997, I was there to see it on the big screen. I have never been able to watch the movie without sobbing straight through from opening titles to end credits.

I sometimes feel like everyone I meet online has seen this movie at least once. Almost all of them have an opinion on the movie. Most of the opinions are strongly polarized: either Ariel is a free-thinking young woman who bravely rejects racism to forge her own destiny and create a lasting peace between two cultures or she’s an idealized anti-feminist icon, complete with Barbie-doll figure and shell bikini, completely willing to throw away her family, her culture, and her own voice for the sake of a man she’s never even met.

Those who fall between these two views tend to stay out of the flame wars. I don’t blame them.

I like The Little Mermaid. I like a lot of things that are problematic, and I don’t think there’s anything necessarily wrong with liking problematic things as long as a certain awareness is maintained that Problems Abound Therein. Art is complicated like that. But I like The Little Mermaid and I think it’s compatible with valuable feminist messages. Certainly, it was my first introduction into a feminist narrative and I have always considered the problematic romance storyline to be camouflage for the real story. But we’ll see whether or not you agree.

Please note that everything I say from here on in is just my opinion.

For me, The Little Mermaid is the story of an Otherkin girl living in a world that is hostile to Otherkin. Ariel is a human born into a merperson’s body, and in a culture that routinely lambasts humans for the very same things that the underwater world does: eat fish. (Seriously. That shark at the beginning who chases Ariel and Flounder is clearly trying to eat them. These are not Happy Vegetarian Fishes.)

For me, The Little Mermaid is the story of a feminist girl living in a world that is hostile to feminist ideals. Ariel is a headstrong young woman who wants knowledge and growth and her own voice, but these things are being systematically denied to her. The only form of learning her father permits is that of patriarchy-approved women’s pursuits: she may study music, but not other cultures.

For me, The Little Mermaid is the story of a culture-conscious girl living in a world that mandates insularity. Ariel wants to learn about cultures and peoples and practices and histories different from her own, but she lives in a world that holds even third-hand study of such things to be utterly forbidden because the power structure believes that the populace is safer if they are steeped in fear and ignorance. (Fearful merpeople won’t try to make contact with the humans, and thus fear maintains their secrecy.)

And now I’ll walk through the film and explain why I feel these things.

The opening titles air over singing humans as they work on the local prince’s pleasure ship / wedding ship / fishing ship. Well, there are three ships in the movie, and they all look pretty much the same to me, so I’m going to assume that Prince Eric has a fleet of all-purpose boats and this is one of them. But the sailors are singing while they collect fish in their nets and Eric (and the audience!) is learning, and here are a couple of problematic things up-front.

One, everyone in this universe is white. (We’re going to be seeing this one a lot in the Disney deconstructions.) Two, this is not a working class universe. Oh, the fishermen are fishing, but this is really the only work you’re going to see in this movie outside of a quick shot of laundry-washing and some cooking. I think Eric’s kingdom is supposed to be one of those picturesque smaller ones where the royalty aren’t far removed from the common folk and don’t mind getting their hands dirty, but it’s kind of a muddled message and it only gets worse when we get to Triton’s kingdom. Let’s just place a big sign over the deconstruction that these are Privileged White People with the inherent issues that inevitably follow.

We pan down under the sea to the King Triton’s Schmancy Music Hall and Combination Throne Room just in time to see Ariel completely fail to show up for a music gig that was intended largely to glorify her father while his daughters display themselves to the populace and use their vocal talents to praise his name. I can’t imagine why a young woman might think she had better uses of her time than to be a public ornament to her father, nor why she might refuse to come to rehearsals (as Sebastian tells us). And when her father realizes that Ariel has failed to show up for the concert, his eyes literally turn red with rage. Yowza.

And here is an important point: Ariel’s dad is abusive. Oh, I think he doesn’t try to be, and I even think he doesn’t want to be, but he is. And I really do think it’s a function of The Patriarchy Hurts Men, Too. You see this clearly in the scenes with Triton and Sebastian: both men shore up each other’s will to be harsher than they otherwise individually would be inclined to be, and they do this because they think it’s expected of them. When Triton is alone and when no one is looking, his face softens, his expression is sad, and he sighs and weeps for the decaying relationship he has with his daughter. It’s when others are looking — notably, Sebastian, the only other adult male in Triton’s scenes — that Triton is at his most abusively fierce.

I don’t think this is a coincidence. Triton isn’t monstrous and Sebastian doesn’t callously bring out the worst in him; they both reinforce each other’s commitment to harmful patriarchy ideals, because they’ve been raised to believe the patriarchy expects them to. Neither is it a coincidence that Triton’s final act of redemption comes after he and Sebastian have revisited a previous conversation and they’ve admitted that they were both wrong and that their actions were harmful. But now I’m jumping ahead.

By giving Triton this characterization, Ariel is immediately given a rich and sympathetic background before she even swims onto the stage. She’s living in a deeply patriarchal and oppressive community where her status as “princess” is largely ornamental and wholly subject to the whims and wishes of her father. While she probably had moments of tenderness between her and her father, particularly when she was younger and could be indulged as a child instead of punished for being a woman, their relationship is strained by his insistence on publicly conforming to aggressive and abusive parenting models whenever anyone is looking. These shifts in emotional tone probably confuse and frustrate Ariel: why is her father so kind at times and yet so harsh at other times? She’s coped with the on-and-off abuse by literally withdrawing. By forgetting rehearsals and the concert and pulling back into her cavern of collections, she’s not passively asserting herself or deliberately catering to the patriarchy; she’s trying to carve out a safe space, mentally and physically.

We are introduced to Ariel who, at great personal risk to her safety — both from the sharks who seek to eat her and from her father who could severely punish her — she is scavenging human items from old shipwrecks. And this… is amazing! Our protagonist is an explorer. What’s more, she’s a scientist, going to a direct source (albeit a bad source, since the seagull is actually ignorant of human affairs, but Ariel has no way of knowing that) to be educated on the items she finds. She wants to understand the humans, and to study the things they do and the items they create. She has a whole secret museum dedicated to all the things she’s collected over the years.

Words fail me in describing how incredible I find this. In another movie, or in a book, there would be more time spent on just how incredibly subversive Ariel is being and has been, for literally years and years. This isn’t a trivial hobby or a girlish obsession; she’s the only person in her culture who is both willing and privileged enough (due to the fact that Triton might not blast his own daughter into tiny bits for breaking his laws) to almost single-handedly set up an entire cultural museum of study on a race of people right outside the kingdom’s doorstep. The sheer bravery and gumption and intellectual devotion necessary for Ariel to have done what she’s done is amazing: she’s essentially created her very own Human Studies department right under the king’s nose because studying other cultures is important, dammit.

I dare you to bring me a Disney heroine who has demonstrated similar levels of bravery, intellect, scientific pursuit, and proactive awesomeness within the first 15 minutes of her own movie.

Then we cut over to Ursula, and… I have mixed feelings about Ursula. On the one hand, she’s a fat woman and a villain in a movie that has problematic body portrayals. Ariel’s sisters are almost uniform in body type, expect for Adella who kind of sort of maybe looks a little bit bigger than her sisters, in the Lane Bryant model sort of way (i.e., same breast and hip proportions, just slightly bigger all over) and who was promptly slimmed down for the sequel because Disney got the memo that fat people are not sexeh because DEATHFATS. The only other fat women in this movie are the castle servants, who are fat in the non-threatening happy-servant kind of way, and the fat woman in the Ursula song who “this one [is] longing to be thinner.” And — rage! — the fat merwoman’s tail extends up and over her breasts like Ursula’s does, but the thin incarnation of the fat woman has the bare-stomach shell-bra combo that Ariel sports. Because nude fat stomachs are obscene and ugly, but thin fat stomachs are normalized and pretty! Grr, Disney.

But! Ursula is sexy. Her breasts! Her butt! The way she moves! Her voice! I don’t honestly remember really… noticing this as a child, but it’s there and it’s largely treated as… normal. Ursula isn’t evil because she’s sexy, nor does she seem really to be evil because she’s fat. She’s just evil and fat and sexy, all in the same package, and I guess that’s kind of cool? I’m not sure. But then when I noticed that in this viewing, I realized that this movie is actually VERY filled with women’s bodies. Can we say that about any other Disney movie?

I don’t just mean the bikinis and the tummies; the women’s bodies here move. Ursula struts realistically around her cave and gods but those breasts and butt are there and they move. And — skipping forward a bit to Ariel’s “I Want” song — Ariel shakes her hips when she sings about “strolling along” the street; she undulates her whole body sensually when she imagines being “warm on the sand.” There are bodies in this movie! And… while they are sexy bodies, I don’t feel like I’m being clubbed with Male Gaze. I like it. I like how it seems to normalize women’s bodies as real, as things that come in different sizes, as things that can be uncovered and sexy and yet not objectified into T&A without a head or a personality needed. I’m just sorry that we have to leave the 1980s in this regard.

Coming back to the movie, Triton yells at Ariel for missing rehearsal. He cuts her off multiple times in this scene, and calls humans “barbarians” which is a nice bit of othering to throw onto the pile of objections to Triton’s character. He then tosses a tone argument at Ariel, which effectively cuts off not only what she was going to say but also punishes her for reacting realistically and legitimately to his bullying. Then Triton tells her that as long as she lives under “my ocean,” she’ll obey “my rules,” which is totally not controlling or an abusive conflation of kingly privilege and parental privilege. And then Triton and Sebastian decide that Ariel, who is a young woman budding into her sexual awakening, needs “constant supervision.” Patriarchy for the win.

And then we have Ariel’s “I Want” song and it still gives me shivers. The opening lines — “If only I could make him understand. I just don’t see things the way he does. I don’t see how a world that makes such wonderful things could be bad.” — reinforce that Ariel is not only longing to be human already, but she’s also inherently more open-minded than her close-minded and prejudice liege-father. Her fantasies of being human conflate with her fantasies of living in a feminist-friendly society where she can speak her mind freely and grow intellectually: “Betcha on land, they understand; bet they don’t reprimand their daughters. Bright young women, sick of swimmin’, ready to stand. And ready to know what the people know; asking my questions and get some answers.”

MORE WOMEN! The picture of fire and the wind up toy that shows dancing both have women in them. The parallel is obvious in that Ariel wants to be these women, but I’m still blown away looking at how many women are in this film in places where I frankly think nowadays they’d be edited out. Maybe it helps that this movie wasn’t made or marketed with the All Important Male Demographic in mind, I don’t know.

Sebastian tumbles out and informs Ariel of what she already knows: her father would be furious if he found out about the museum. Which makes so much sense, really, that his racial hatred of humans extends so far that he would deny his subjects the ability to even study them, if only to come up with more effective ways of avoiding the humans, because studying leads to understanding and understanding leads to compassion and compassion doesn’t mesh well with racial hatred. And, yes, I know they’ve woobied him up with two decades’ worth of backstories and personal tragedy, but I think that waters down the message that sometimes even people we love can be racist assholes.

We zip up to the surface for Ariel to see Prince Eric and for some character establishing shots. And I have to say that Eric is probably my favorite Disney prince. He’s hanging out with his working class and while that could be seen as slumming, he doesn’t seem to mind getting rope burn on his hands and he knows how to steer the boat, so he’s at least not adverse to learning. And he goes back to a fiery burning ship to save his dog.

Ariel saves his life.

They didn’t have to do it this way. They could have had Ariel and Eric catch a glimpse of one another and fall in love that way. Ariel could have been singing in a quiet grotto and Eric could have been drawn to the sound and seen her for a split moment before she disappeared. It would have been pretty and feminine and sweet. But they didn’t do that. They had her proactively search the burning wreckage of a ship, and drag an unconscious man to safety on the shore. And that tells me two things. One, in 1989, being saved from death by a woman didn’t emasculate you forever in the eyes of the (probably) male screenwriters. Two, in 1989, saving a handsome man from drowning was considered an acceptable female fantasy with all the strength, verve, and determination that accompanies that.

Haha, no, there’s totally not a backlash against feminism today in 2012. IT’S ALL YOUR IMAGINATION.

Sebastian tries to convince Ariel that life under the sea is better than life as a human. He has a jazzy musical number and Ariel gives him quirky yeah-I’m-not-buying-it looks before it becomes clear that she’s not really needed for this song routine and goes off with Flounder. And here is a big ol’ world-building mess because apparently the fish neither work nor eat, and they all live off of plankton delivered to their doorstep every morning by magic. Or so Sebastian seems to think from his position of Privilege? I dunno. This is why deconstructing movies with talking animals is hard.

Triton calls Sebastian into his throne room and interrogates Sebastian while cheerily pointing his weaponized triton at the little crab. Haha, that is not scary at all! Sebastian breaks down and tells Triton about Ariel’s museum, and Triton shows up and brutally destroys it all while she weeps and begs him to stop. And this scene? Wrecks me every time. The bit with Triton building himself into a rage — “One less human to worry about! … I don’t have to know them — they’re all the same. Spineless, savage, harpooning fish-eaters, incapable of any feeling…” — is both horrifying and priceless because it really gets through how xenophobic and racist Triton truly is. He doesn’t care that he’s frightening his daughter; the rage has built in him to a point where terrorizing her makes more sense to him than actually talking to her or doing anything other than abusing his position as both king and father.

And this scene is so utterly valuable. Because now Ariel will go to the sea witch and trade her entire life away (and her voice) to go chase after a man she’s never met. Remember that anti-feminist message referenced way back up there at the beginning? But that’s not what she’s doing, not really. As much as Ariel laments in a moment that “If I become human, I’ll never be with my father or sisters again,” her father has driven her away. Ariel isn’t safe under the sea, not emotionally or psychologically. Her life’s obsession with studying and understanding and educating herself on human culture will never be accepted — and if she persists in trying to do so clandestinely, it will only be a matter of time before someone discovers her secret, betrays her to the king, and all her work is destroyed. She knows that fate is inevitable, because it’s just happened not ten minutes ago.

Ariel can either go home and be a good mermaid and play with her hair and go to voice rehearsal and marry a merman who will never share her interests or understand her and she can live and die frustrated and unfulfilled. Or she can take a chance and become everything she’s ever wanted: a human. And she can become that human by finding true love — “Not just any kiss,” Ursula cautions. “The kiss of True Love.” — with the first human she’s ever met, a man who attracts her with his courage and bravery and adventurous spirit. It’s a gamble, and possibly not a good one, but it must seem like the one hope for happiness left available to her.

Human! Ariel washes up on Prince Eric’s beach and is taken for a traumatized survivor of a shipwreck, which seems plausible enough. And while I’m not 100% sure I like Grim pressing Eric to woo the traumatized survivor of a shipwreck rather than, say, provide for her education and psychological care and place her in the best possible position to choose how she wants to live the rest of her life, I do love that Eric is shown as being highly reluctant to treat Ariel with anything less than courtesy and respect. A privileged man who doesn’t react to a pretty half-naked woman washing up on his beach like Christmas has come early? Yes, please.

There’s a scene with a French chef that is so heavy on the cultural stereotypes that I don’t even know what to say. I was going to say that this was one of the only animated feature film songs that features a foreign language, but then I remembered the Charo song in Thumbelina, which is also heavy on cultural stereotypes. *sigh*

Then Eric and Ariel go on a tour of “his kingdom,” which seems to basically be this one decent-sized town, and Ariel is in complete Manic Pixie Dream Girl mode, but for once this makes sense because everything she sees is literally new and exciting and amazing and a dream come true. And then he lets her drive the carriage and she loves it and clears an oddly-placed death-defying jump and once the panic passes, Eric settles back like this is the good life and Ariel is clearly having a ball. I think that’s sweet, frankly.

And then there’s a lot of singing and near-kissing and Ursula showing up to ruin things and Ariel being towed out to the ship which is not nearly as awesome as her swimming out there under her own power, and I get that it makes sense that swimming-with-legs would be something she’s not mastered, but still it feels like the Feminism Power has run out, and then Ariel and Eric reunite just in time for it to be TOO LATE and Ariel is a merperson and Eric does not care even a little bit because Eric is not a racist asshole like Triton. And then Eric saves Ariel’s life with a harpoon while Triton watches, and this is hilarious given Triton’s earlier rant about humans-who-wield-harpoons.

After the exciting showdown scene, Eric recovers slowly on the shore while Ariel watches from her rock. Triton and Sebastian watch from further out, with Triton realizing that she really does love him and that this hasn’t all been About Him and her special butterfly rebellion. Gee, ya think? Sebastian tells him “children got to be free to lead their own lives” and Triton references as earlier conversation where Sebastian said the opposite. And this is the moment where everything is unspoken, but for me it seems like they’re saying yeah, this whole Patriarchy thing is garbage and we were wrong. And then Triton gives Ariel her legs back, she marries Eric, and there’s a new era of peace for both kingdoms, and it is awesome.

And… yeah. It ends in a 16 year old marrying a guy she’s known all of three days. (Assuming we don’t go with the standard handwave that between cuts there could have been years and years of dating that we didn’t see. Because movies don’t work like that.) And, devoid of context, that is Very Problematic. Hell, even with context, it’s not something that gives me warm fuzzies. I do not like the Mandatory Marriage at the ends of these movies, or the implication that it’s not a Happy Ending without one. And I like the Mandatory Marriage even less when it happens to two teenagers (or one teenager and one guy in his early twenties) who’ve known each other only over the course of a few adrenaline-packed and hormone-driven days. I don’t feel like this is a healthy formula. So there’s that.

But it’s also one of the few movies I can think of where an Otherkin protagonist gets the form she’s always felt was really hers. And it’s a movie where a brave young woman defied the racist and xenophobic laws of her homeland in order to create a greater understanding between two cultures and almost single-handedly engineer a peace between both kingdoms. And she did all this while she was sixteen, as a young woman in an abusive family where she was only valued for her ornamental status. She held on to her inner essential self and managed to forge her own path without ever once beating herself up for the abusive things that others did to her. Throughout the movie, the entire narrative seems to scream that being strong-while-female is not a bad thing: it’s okay to defy your racist asshole dad, it’s okay to save the life of the handsome guy who won’t then turn around and act all emasculated and shun you, it’s okay to own your “acceptably feminine” talents in ways that make you happy, social expectations be damned. And for a movie that is now over twenty years old, that seems kind of awesome.

Ana’s Happy Feminism Fuzzies Scorecard

– Otherkin narrative where protagonist proactively gains the form she wants

– Feminist narrative where protagonist longs to be taken seriously as a cultural researcher

– Intellectual narrative where protagonist values museums and cultural study

– Racial/Cultural narrative where protagonist demonstrates that Racism Is Bad

– Body Positive (with caveats) narrative where women characters abound of different body sizes

– Patriarchy Hurts Men narrative where good men are abusive because of patriarchal expectations

Ana’s Sad Epic Fail Scorecard

– Narrative that is entirely cast with white people and has a Angry French Chef stereotype

– Narrative that contains muddled class portrayal and is largely about privileged people

– Narrative that contains no openly QUILTBAG characters

– Narrative that ends with a teen marriage between two almost-strangers

Final Thoughts: The Little Mermaid is — like most Disney movies — rife with issues of class, race, hetereonormity, and body portrayal. But in my opinion it’s ironically one of the least problematic movies in the set (“ironic” because the current cultural narrative is that we’re now BETTER at those things than we were in the 1980s), and if you’re a white heterosexual class-privileged girl living in an oppressive patriarchy — as I was when I came to the movie — it may just resonate with you. Maybe.

———-

Ana Mardoll is an avid reader and writer. She loves cats, fairy tales, and intense navel gazing. She blogs on a near daily basis from an undisclosed location in the wild, untamed, and astonishingly dusty Texas wilderness. Her photo-realistic avatars are a gift from best friend and invaluable writing buddy, J.D. Montague.

To read more of Ana’s writings, including her snarktastic literary deconstructions, visit her website at www.AnaMardoll.com.