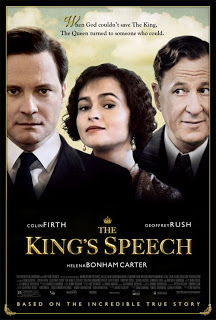

Prince Albert is “Bertie” to his inner circle (

Colin Firth), and has a debilitating stutter, but the British Empire needs him to step up into his father’s Kingly shoes (George V, played by

Michael Gambon), and be a powerful orator. Bertie’s ability to lead is intricately linked to his ability to speak, particularly as the World War approaches, and the changing tides of technology make worldwide radio broadcasts ubiquitous for all rulers. With quirky but powerful help from speech therapist Lionel Logue (an inspiring

Geoffrey Rush), and the charismatic support of his wife (

Helena Bonham Carter as Queen Elizabeth), Bertie overcomes his speech impediment and goes on to, as a final title card states, become a symbol of resistance against the tide of Nazism. Or so the movie would have us believe. What’s also true is that

The King’s Speech is a lovely, ingratiating film about the lavish family behind a violent colonialist empire erupting in a tide of human protest during the very period of the film.

I live in New York City, and when I went to see the film in Union Square, it had already been nominated for a whopping 12 Academy Awards. It was a packed movie house, and even in the midst of the most diverse locale in America, the audience was almost exclusively older, white couples. To be clear, I liked the film, and I’m not suggesting it needed to broaden its treatment of the King as, say, the British Raj. But if this audience was any indication, most people walked away from The King’s Speech without understanding to whom exactly we’ve been so adeptly ingratiated.

The film is book-ended by two pivotal public speaking engagements for Prince Albert, who later ascends to the throne as King George VI. The film opens in 1925 at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Stadium, and closes in 1939 with a global radio broadcast declaration of war with Germany. To contextualize this time period, in 1925, M.K. Ghandi had recently been released from a two-year prison sentence awarded by order of the British Raj for his galvanizing leadership in the anti-colonialist Indian Independence movement. 1930 saw M.K. Ghandi leading the galvanizing Salt March through an economically crippled India, a strategic moment in sovereignty struggle. As I watched, laughed, and rooted for Bertie to speak with all his might, I couldn’t help but reflect upon the worldwide impact of his every word. It is always worthwhile to qualify any fawning, particularly in a rather segregated western popular culture market. That being said, The King’s Speech is a loveable film framed around acute performance anxiety, something we can all relate to.

It took a solid team led by Director Tom Hooper to create this uniquely intimate period film. Period films can come off stuffy, but here the outdoor shots glint with bracing, misty energy and the indoor shots are defined by palpable, direct-gaze intimacy. Recall the intriguing approach of Elizabeth’s chauffered car creeping along cobblestone streets towards Logue’s home, horse drawn carriages and other period mise-en-scene coming in and out of fog. There was the dewy sunlight of the sculpted garden scene where Bertie, nursing wounds from a scathing run-in with popular brother David (Guy Pearce as King Edward VIII), walked away from Logue in a fit of defensive anger, his sharply outlined shadow trailing him like an afterthought of remorse. Internal shots are palpably and unusually intimate. Take for example, the film’s numerous peeks into Bertie’s mouth, gargling, inadvertently spitting in effort, or full of marbles. There is the stark, dignified honesty of the curling turquoise decay that marks the wall in Logue’s speech therapy room.

Notably, the film tends towards flat, pictorial frames, direct eye gazes, and close-up, slightly de-centered frames. Manohla Dargis, in her New York Times review, bemoaned Hooper’s “unwise” use of the fish-eye lens as a too literal metaphor for Bertie’s life in a fishbowl. But I found the close-ups ultimately supportive of the film’s overall tone. A direct gaze shot of Logue at the head of his family dinner table suitably emphasizes how this very place, from where he is now looking at us, is perhaps the only place where this talented yet under-employed therapist retains a sense of power.

It cannot be said that this film has any meaningful roles for women, who are simply not the focus in this story. No matter how much is written about Helena Bonham Carter’s canny and compassionate Elizabeth, the film boils down to cinematic basics when it comes to women. There are two doting wives (Jennifer Ehle as Myrtle Logue), one frowned upon mistress (Eve Best as Mrs. Wallis Simpson), and three rather doll-like daughters. Aside from a small battle of wills between Bertie and Elizabeth (in which we taste a tiny bit of her wry cunning as the Red Queen in Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland ), there is not a hint of nuance for any female role. No, you don’t watch this film to see women shine. Instead, what makes The King’s Speech unique is its tender treatment of a relationship between two men, Logue with his power to heal, and Bertie with his power to rule.

), there is not a hint of nuance for any female role. No, you don’t watch this film to see women shine. Instead, what makes The King’s Speech unique is its tender treatment of a relationship between two men, Logue with his power to heal, and Bertie with his power to rule.

Rarely have I seen such exploration, such daring vulnerability in the portrayal of male relations on the contemporary western cinematic screen. Perhaps being the King of an Empire allows for this intimacy, because regardless of how vulnerable Bertie reveals himself to be, he still rules. The King and his unlicensed speech doctor navigate class differences adeptly, heartbreakingly, on their way to foraging the trust needed for Bertie’s impediment to heal. While Logue is humble, he never concedes honor, and it is this adroit balance that allows us to willingly follow where he may take us, especially when the road is audacious (casually calling him Bertie! making the King cuss and roll about on the floor!). For Bertie’s part, it is painfully evident that he rarely, if ever, had a truly intimate relationship with another man. His father nit-picked and neglected him, his older brother demeans him with ferocious skill, and a stuttering would-be King is born. The awards Colin Firth is racking up for his portrayal of Bertie surely have to do with his ability to embody the process by which a rock of defenses sincerely and helplessly cracks open.

By all pre-Oscar indicators, The King’s Speech is securely in line for recognition at the 83rd Academy Awards ceremony. The question is, what will the film garner stateside, given stiff competition from critically fawned-over flicks like The Social Network and Black Swan?

The King’s Speech swept in five major categories at the UK Oscars, otherwise known as the BAFTA Awards (British Academy of Film and Television Arts). This was a resounding showing despite an arguable snub by the British Film Institutes monthly magazine, Sight and Sound, in their popular top ten poll.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the film hasn’t fared as well stateside, but it’s still getting some shine. Lead actor Colin Firth won a Golden Globe and a SAG Award (Screen Actors Guild), and the film earned another SAG for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture. If I had to predict, I’d say The King’s Speech will at best win in one major category (that won’t offset the domestic darlings from their perch), such as Best Supporting Actor, and in one or two less high profile awards such as Best Original Score. If you haven’t already seen it, go see it while it’s still in the theater, especially if you know what it’s like to quake a little before a public performance of speech or song. The film’s intimate look at the somatics of sound and breath will get you in the gut, and before you know you’ll be laughing and rooting hard for the King. But do me one favor, just don’t forget who you’re rooting for.

Roopa is finishing her Masters in Cinema Studies at Tisch/NYU, and got her law degree from UC Berkeley in 2003. She loves writing and teaching about the political context of contemporary popular culture, and often blogs at her site, http://politicalpoet.wordpress.com. And truly, she can’t believe how much The King’s Speech had her empathizing with the damn Raj.