Boardwalk Empire returned for its fourth season on Sunday, Sept. 8. This season is poised to continue important representation of struggles involving gender and race in the award-winning show, which is aesthetically gorgeous and well-written.

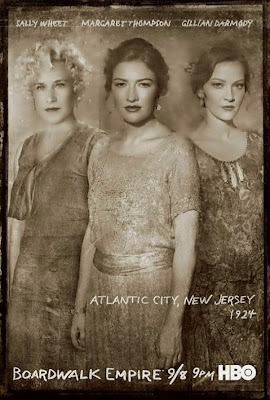

The few, but incredibly important, female characters on Boardwalk Empire are fascinating. I wrote last year about the remarkable story lines in season 3 that focused on birth control and reproductive rights. Boardwalk Empire has always kept a keen eye on women’s issues–from suffrage to health care.

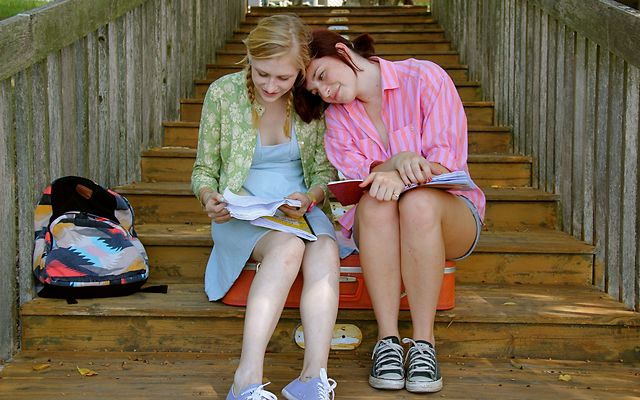

Season 4 is set up to be more of the same–long-form debauchery and violence with moments of poignant sub-plots featuring the female characters. Gillian is slipping deeper into a heroin addiction, and is selling herself instead of selling her house. Cora escapes a violent bedroom scene (which we will revisit in a moment). A young actress attempts to take Billie’s place in Nucky’s life for her own gain, but he rejects her. Richard has traveled to reunite with his twin sister, Emma, on her farm.

As often is the case in these seemingly masculine dramas, women are essential to the plot, even if they often aren’t the focus of most reviewers, or even the bulk of the action. Nucky is king, Al Capone is pulling strings, and Chalky is set to be a power player.

|

| Drink, talk, shoot, repeat. |

But those moments that the women of Boardwalk Empire are on screen are among the best of each episode. Their parts are small. Their scenes are brief. But each is meaningful and powerful. The women characters are complex–evil, moral, conflicted, good mothers, bad mothers, addicts and everything in between. They are three-dimensional. This is a good thing.

The female-centric subplots in Boardwalk Empire are treasures buried in a pile of empty whiskey bottles. Most reviewers, however, focus on the men. Hollywood Life only mentions the male characters (except for the mention of Nucky getting smarter about women). The Huffington Post mentions Gillian briefly and Cora (but not by her name). Rolling Stone does do a better job of fully describing and summarizing the episode.

The fact that critics often ignore or reduce women characters isn’t surprising, although it’s always frustrating. What’s horrifying, however, are a few critics’ responses to the aforementioned violent sex scene.

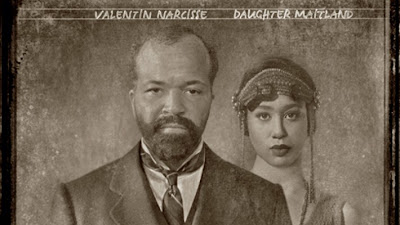

Just like Boardwalk Empire has woven in subplots of women’s struggles, it has also presented the endemic racial tension in Nucky’s world in a way that makes viewers uncomfortable (especially since our culture is still so steeped in racism). Not everyone seems to get this, though.

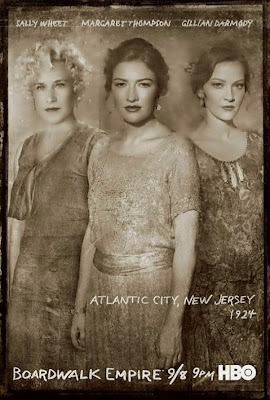

|

| From left, Dickey, Cora, Dunn and Chalky. |

At Chalky’s new club, he sits watching the new talent with his right-hand man, Dunn, and a white talent agent, Dickey, and his girlfriend, Cora. Cora sketches an erotic drawing of her and Dunn, and asks him to come upstairs. The two start having sex, and Dickey makes himself known in the room as he draws a gun against Dunn. Dunn scrambles to put on his pants, and Cora immediately says he had forced her. This is all a game, though, for Dickey and Cora. Dickey forces Dunn to resume having sex with Cora, and all the while Dickey is throwing racial epithets, heavily peppering his slurs with the N-word and claims about how black men behave.

Dickey starts masturbating. “It’s all just some fun,” Cora says with a smile.

Then Dickey says, “There’s no changing you people.” With this, Dunn breaks a bottle over Dickey’s head and proceeds to stab him repeatedly and viciously. We are surprisingly comfortable with this outcome of the scene, because Dunn’s humiliation and objectification is so visceral, as is the racism. This scene is indicative of not only the racism and degradation of black Americans at the time (echoed by Nucky’s almost-mistress who says the Onyx Girls are “deliciously primitive”), but also the demand that they perform as objects for whites’ entertainment and sexual purposes, without agency. The power that Dickey wields over Dunn–his whiteness, his gun, his hand down his pants–is nauseating and historically accurate. This scene is about racism. This scene is about power, humiliation and resistance when one is caught up against a wall of disgusting degradation.

However, the aforementioned reviewers had a different reading of this scene.

From Hollywood Life:

“…Chalky finds out that being the boss requires a lot of cleanup. Like when after his sidekick Dunn Purnsley (Erik LaRay Harvey), in the most awkwardly violent scene of the episode, murders a booking agent after the guy catches him sleeping with his wife — and then forces Dunn to continue while he watches. Boardwalk Empire, ladies and gentlemen!”

Certainly a brief show recap isn’t always the place for heavy cultural analysis, but to brush off the scene with such flippant commentary? Privilege, ladies and gentlemen!

“So Dunn did what he had to do, smashing the guy’s head with a liquor bottle to get himself out of danger. And then he went the extra murderous mile, repeatedly stabbing the guy in the throat with the broken bottle, because it’s Boardwalk Empire.”

Are you kidding me? Dunn murdering Dickey had nothing to do with him being in danger. It had everything to do with him being degraded and humiliated.

Rolling Stone acknowledges Dunn’s true motivations, but still misses the mark:

“He may have moved up the ranks from jail antagonist to kitchen worker to Chalky’s right-hand man, but Dunn doesn’t know shit about doing business, especially with white folks in 1924. I can’t blame him for pounding a broken bottle into Dickey’s face repeatedly – not only was he forced to have sex with Cora at gunpoint, but Dickey degraded him even further with regular use of the n-word and vicious taunts like, ‘There’s no changing you people.’ Except Chalky knows that you can’t go around killing Cotton Club employees (Cora manages to escape) just for ’15 minutes’ worth of jelly.'”

Yes, perhaps Chalky knows how to do business with white folks, but his “jelly” comment is inaccurate–that’s not what Dunn killed for. Except for killing Dickey (which even this reviewer acknowledges a motivation for), Dunn didn’t really do anything wrong.

And perhaps most egregious, buried in an approximately 2.5-million-word recap from New Jersey:

“‘It’s all just some fun,’ the wife assures. Not to Purnsley who, after they begin the humiliating deed, blasts a whiskey bottle clear across Dickie’s face. It’s doesn’t just stop there, however, the beating continues until the booking agent is dead and his wife, in horror, escapes through the window, naked. Purnsley stands there a bloody mess.”

There are some pretty pertinent details missing here. In this review, Dunn seems to be painted as a savage villain, lashing out for no clear reason. That’s not what happens.

Reviewers saw Dunn acting in self-defense (which further reduces his perceived power), not understanding how to do business with white people (blaming his sexuality and ignorance), or lashing out in savage violence without clear motivation.

Reviewers ignore the implications of racism.

Reviewers sideline female characters.

Reviewers do this because too frequently, the lens they are looking through is of the white male experience. This is privilege.

Even when the artifact itself deals with gender and race in a way designed to challenge viewers, reviewers often overlook it. I was uncomfortable, horrified and excited during the premier of Boardwalk Empire this season. I continue to see complex female characters and pointed commentary on racism.

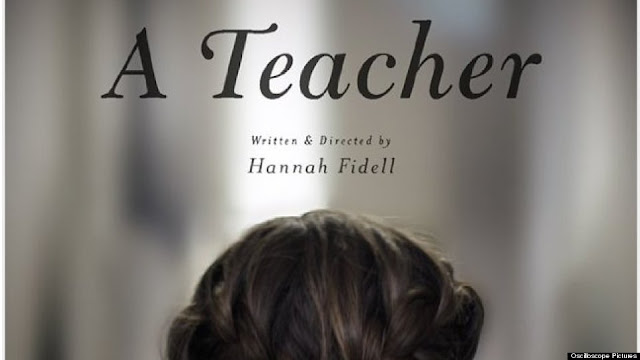

|

| Sally, Margaret and Gillian. |

I’m disappointed, then (and even horrified), when critics ignore these aspects, or get them terribly wrong. Their recaps and analyses help shape the conversations surrounding these shows, and if they just focus on those smoke-filled rooms and the power brokers, without fully paying attention to the other characters, they are insulting women, people of color and those who work so hard to write about and represent them.

However, if we can look past the critics, there is much to be excited for in season 4. Still to come this season, Patricia Arquette will play a speakeasy owner and Jeffrey Wright will play a Harlem gangster who is seeped in the politics of the Harlem Renaissance. These moments that have made Boardwalk Empire exceptional–the moments of clear gender and racial historical context and commentary–are poised to take center stage in season 4. Hopefully we can all look through the clouds of white male smoke to see what lies ahead.

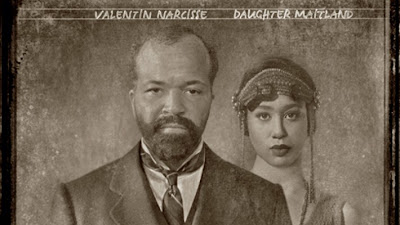

|

| Valentin and Maitland |

________________________________________________________