|

| Bend it like Beckham film poster. |

Written by Janyce Denise Glasper

“You bitch!”

This thunderous exclamation seems to occur every five minutes. If a girl is way prettier, she’s a bitch. If a girl “steals” a man of a girl who isn’t even dating that said man, she’s a bitch. If a girl is thought to be a lesbian, she’s a bitch. Twice Jesminder “Jesse” Bharma, Bend it Like Beckham’s football loving protagonist, has been on the receiving end of the blow, but I started to lose sight of this supposedly empowering feminist sports movie due to the infinitely alarming amount of lesbian hatred disguised as harmless humor. To be a lesbian is a bitch? Really? Why?

|

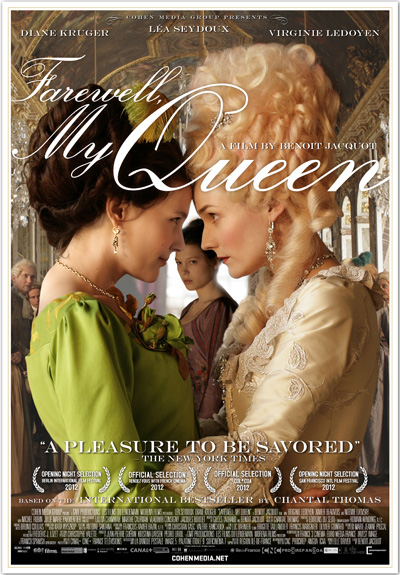

| Joe the coach (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) makes damn sure that Jesse (Parminder Nadra) is no lady lover. |

Lesbianism appeared to be an invisible villain to both Jesse and her equally talented teammate, Juliet “Jules” Paxton—a horrendous nasty vile “disease” that could only arise from women who enjoy contact sports.

In Gurinder Chadha’s debut feature film, Jesse is inspired by David Beckham and has his posters and jersey decorating bedroom walls. She wants to emulate his prowess and expertise on the football field and certain people think that it’s not only his athleticism that propels her. She might just like women too. Jesse’s mother hates that she doesn’t want to be called “Jesminder” or act more feminine and domesticated.

|

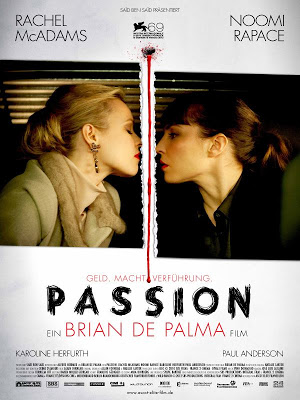

| “We aren’t lesbians! We both love Joe!” Jesse (Parminder Nagra) and Jules (Keira Knightly) should have chanted. |

Jules notices Jesse’s skills against the boys and asks her to join a local team. Jesse eagerly agrees and plays in secret, knowing that her parents would greatly disapprove. Jesse and Jules start to build a positive relationship with Jules schooling Jesse on the amazing Mia Hamm, one of many American women football players in action. The close twosome begin sharing dreams of becoming an active member of the overseas sports team.

Jesse’s parents and Jules’ mother Paula are horrendously incomprehensible characters for sexist views about women’s lock length.

“They wear their hair so short these days, you can never tell,” says Jesse’s mother, twice.

This supposed to be a joke, but why?

Hair length is such a sensitive topic to women, especially when length is close cropped and called “boyish.” No one ever seems to really comprehend the meanings behind hair and what it truly says about someone. Whether a woman likes it away from their face, hate strands touching their butts, donates tresses to worthy causes, wears a protective scarf, or battles cancer or other form of loss, hair is worn differently by all women of all cultures and creeds and shouldn’t be a mark set against them if it’s above shoulders or just plain bald. Feminism should not be marketed towards hair, but unfortunately it always has and will be. Lesbians also wear their hair in various styles and the short hair cut is so beyond stereotypical. It isn’t that powerful to make fun of a group of women or use them as a catalyst to drive laughter. Lesbians also are people too– not a dirty circumstance.

When Pinky’s wedding is called off due to her fiance’s parents seeing Jesse and Jules “kissing,” Pinky is enraged and calls Jesse a bitch for ruining her life. So yes, lesbianism is so treacherous, it gets in the way of events like holy matrimony. Chadra’s co-written screenplay entails all the wrongs of same sex pairings, using misunderstandings as trivial humor– seen by both Jesse and Jules’ reactions to hearing that their families believe them to be drawn together and not to boys. It fails miserably at being sentimental to lesbians as a whole.

|

| Jesse (Parminder Nagra) and her sister Pinky (the awesome Archie Panjabi) both look surprised by Paula (offscreen Juliet Stevenson) announcing that Jesse is part of a lesbian couple with Jules. |

“Mother, just because I wear trakkies and play sport does not make me a lesbian!” Jules tells Paula, as if lesbianism the most foul label ever.

Bitch is fine. But lesbian is a slap to the cheek.

Paula was the absolute worst.

Now what if Jules really were a lesbian? If I were in Jules’ shoes (or cleats), I wouldn’t explain a damn thing to rude, insensitive Paula. For Paula to coldly burst into Pinky’s wedding and “call out” Jesse wasn’t exactly classy even if she tells Jules that she wouldn’t have minded Jesse and Jules being a couple. However, didn’t she not just yell for Jesse to get her “lesbian feet” out of her shoes? That doesn’t sound like someone who would’ve been supportive. Perhaps this is to be a humorous notion (still finding it hard to laugh), but politics on a woman’s style of hair and dress to be considered masculine instead of powerful and sophisticated is outrageous! Not only can’t women have short hair without being labeled manly, we cannot wear pants everyday because that’s an acute sign of lesbianism! Oh and if we play sports especially football, we might not like boys…..

It’s a shame that Jesse and Jules’ fallout had to be over a man– Joe, the coach.

|

| Joe is going to see Jesse (Parminder Nagra) in a new light thanks to “The Makeover” by Jules (Keira Knightly) and Mel (Shaznay Lewis). |

Joe trained Jesse hard on the playing field and shared a couple of his old football glory days prior to injury, but the moment Jesse wore makeup, a form fitting nearly backless number, and long wavy hair cascading about shoulders, he gazed in that beseeching manner that is supposed to be considered romantic. Awww. He really likes her outside of uniform and ponytails.

Pish posh!

This just truly means that her fuckability status moved up and sports took an immediate backburner! All of a sudden Jesse is hot stuff and Joe wants to have his sample, asking her to dance and almost taking advantage of her drunken state at the club celebration. Now the film has switched over from thrilling lady sports to a man getting his power on– thankfully for a few minutes at a time. A friendship gets spat on over a man. It becomes war between Jesse and Jules and that “you bitch!” comes bursting out like a launching torpedo—expected but crappy nonetheless. Jesse and Jules make it abundantly clear that they don’t want each other, but they sure do want that Joe.

However, pissed over the typical women falling for the same man BS, I respect that they don’t battle over the spot for the American team. Irate Jules took the time to seek out Jesse because she knew that Jesse was needed. When they played football, they were in it together, functioning, reacting, and showcasing talents together, victorious champions on the field, telling the world that women can kick around a soccer ball, that their dainty feet can work just as craftily and aggressively as a man. They put differences aside with cleats, game faces, and their other female counterparts to take on one hell of a win! Jesse and Jules prove that just because playing sports is considered a masculine way of showcasing aggression, women too can be rough, wield scars, and sweatiness.

Those kisses? Those hugs? That’s a female’s version of the butt taps that male athletes do. Why factor more into that?

|

| The girls win big! |

After all, the moral of the story is that girls can play sports and like boys– not be one of those scary lesbians!

I applaud Chadha’s direction, but let’s lay off the meanness next time.