|

| Days of Our Lives, one of four surviving daytime soap operas on television. |

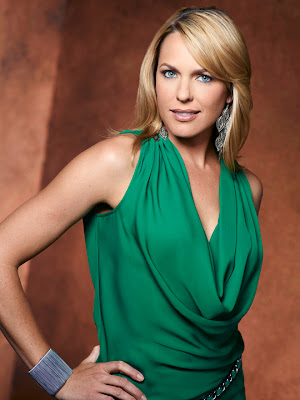

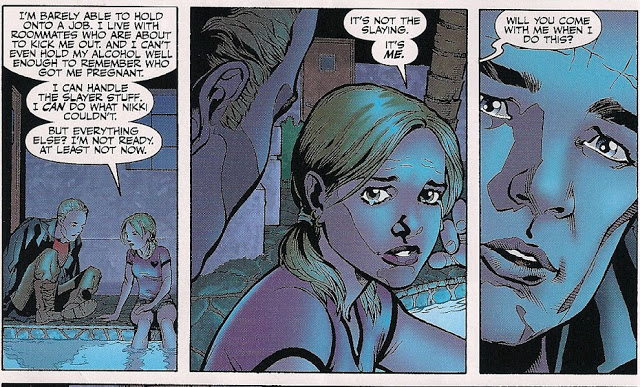

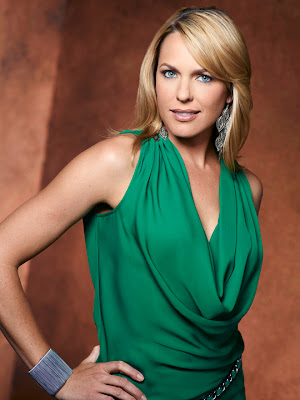

Since 1998, Nicole Walker, played by the very talented Arianne Zucker, has been the scheming, manipulative, alcohol twirling villainess of fictional Salem, Illinois on Days of Our Lives. Always fully equipped with funny one liners from sharp-edged tongue, the former porn star was a golden afternoon escape to laugh along with as she carried out an arsenal of twisted scheme upon scheme, each one more bizarre and hilariously entertaining than the last.

Of course, as is always the case with a female soap opera character, pregnancy enters her womb, even when she doesn’t want it to, but for Nicole, this is no grand blessing of joy and glowing retribution. Years ago, Nicole had been shot and told that she would never carry a child to term, but in these two shockingly “miraculous” pregnancies occurring in 2009 and 2012-2013, the writers have both rewarded and severely punished her, creating and taking away a motherhood that wasn’t supposed to happen in the first place.

In turn, these two miscarriages would altar the character.

|

| Nicole Walker (Arianne Zucker) is one of the resident bad girls on Days of Our Lives. |

Now I’ve watched soap operas with my mom for a long time, viewing them since around age four and almost always the biggest stories revolved around babies. A woman holds onto a man who doesn’t love her by using a baby (usually revealing this “secret” at large publicly attended events like weddings and galas for stun factor); a woman hides her baby for protective purposes; or a baby brings lovers together (rarely). Not a female character alive in the soap opera kingdom is immune to Baby Fever (unless under the age of sixteen or written off), and Nicole is no exception.

In 2009, when Nicole has her first miraculous pregnancy, she is elated and overjoyed, but unfortunately she is having a baby with a man who loves another woman, longtime nemesis, Samantha Brady.

Many Nicole fans were upset by this turn of events, that she could come back into town after a brief hiatus, get pregnant from an elevator ride with EJ Dimera, and become interloping fodder to break a potential couple apart with typical baby dynamite.

It is likely difficult in the soap opera business to continue bringing sharp and innovative stories to the forefront, especially with many of these daytime serials getting the boot for not being hard-edged enough to retain a modest amount of dedicated viewership, but must Nicole be strapped down with a baby? It was far easier imagining her holding little dog Pookie and a cocktail than a blue or pink bowed bouncing baby and rattling pacifier. Her antics and nonsensical plots were stuff of legends–from moneying up, planning murders, and having some of the best fantasy sequences ever. This new found bundle of joy was meant to “soften” brash personality, mature character, and settle her into that domestic place.

|

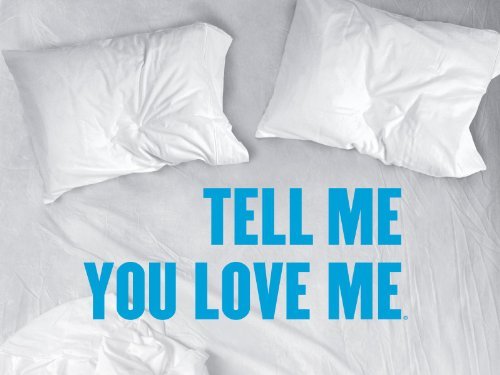

| Nicole (Arianne Zucker) in the throes of a heartbreaking miscarriage. |

The first miscarriage turned Nicole into a stark raving tearful mess and in turn, garnered very emotional scenes of raw poignancy that gave Arianne Zucker her first Daytime Emmy nomination for Outstanding Supporting Actress. Mourning the loss with on and off again lover/friend, Brady Black, amongst sobbing agony, it wasn’t just losing the baby that demolished Nicole’s spirits, it was losing EJ whom she knew was only marrying her for the “miracle” pregnancy alone.

But that quickly evaporated into a scheme, especially when she learned that Samantha was also pregnant with EJ’s child. Taking matters into jealous and scarily obsessive hands, she found another pregnant woman and switched her baby with Samantha’s so as to have EJ raise his own child underneath the Dimera Mansion’s opulent rooftop. It was one hell of a warped story, and Nicole had masterminded the whole ludicrous charade all while wearing a false padded belly.

|

| Nicole passes off stolen Sydney as daughter to her and EJ Dimera (James Scott). |

Now a primary reason Nicole stole Samantha’s baby was because Sydney had been Samantha’s fourth birthed child, and Nicole figured that since Samantha had so “many” children, she wouldn’t miss one. Though these two women had been pitted each other through shared loves and public catfights, it was quite disheartening that Nicole’s underlying envy factor lie in Samantha’s fertility. After Nicole had undergone such a traumatic loss, her sudden aspirations for child rearing and baby cribs seemed to have been murdered by foe “flaunting” her healthy offspring like trophies, leaving a vengeful Nicole with the sinking “I Got Pregnant and All I Got Was This Lousy T-shirt” depression.

Nicole’s state of traumatic empathy and grief served as catalyst to her anger directed at ripening Samantha who was about to birth EJ’s child, unbeknownst to him. But Nicole all angry, spiteful, and hurt, instead of normally mourning the loss together with her fiance and telling him of her discovery, blames Samantha and seeks to punish her enemy’s productiveness by stealing a baby as though it were money or a car, not an innocent life.

The soap opera scenario of baby switching is nothing new, but it questions the state of female ethics. Are we really so shallow and vain to be upset over a woman with an abundance of children and look down at our own empty bellies as a statement of unworthy shame? It doesn’t make us less healthy or less happy if we’re found to be barren, but Nicole saw her miscarriage meaning the end of her dreams–of a joy some viewers didn’t realize she wanted.

Nicole and Samantha became “friends” in the midst of Samantha grieving the death of a baby she thought was hers while Nicole greedily held onto Sydney, not wishing to let go of her marriage “security” and motherhood. I felt torn in this agonizing situation because, despite several traits these former enemies shared (such as sexual abuse and family disapproval), a friendship built on lies won’t last.

|

| Samantha (Alison Sweeney) and Nicole (Arianne Zucker) are back to their public displays of violent affection. |

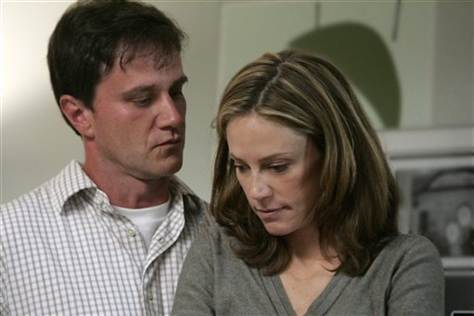

Again in 2012, Nicole finds herself pregnant with another EJ baby, but out of spite, she decides to let another man play father–Rafe Hernandez, Samantha’s soon-to-be-ex-husband (spot a pattern here?). Nicole is farther along in this pregnancy when it’s gruesomely discovered that the baby has been dead inside her womb for weeks. Hit by another emotional bullet, devastation cuts painfully as the torturous dangling of motherhood waving in front of her like a piece of fish bait cruelly floats away. But she keeps this secret all to herself, curled up and bottled into a rage that she hurls against another woman–Jennifer Horton, mother of two and object of Nicole’s latest obsession, Dr. Daniel Jonas.

|

| Nicole (Arianne Zucker) is about to receive devastating news on fate of second “miracle” baby. |

Once the truth comes out about Nicole’s second miscarriage, embarrassed and guilt-ridden, she relives the agonizing suffering of losing another chance at motherhood. Coming to terms with barrenness, she is ultimately driven to suicidal infliction too painful to watch.

Days of Our Lives writers appeared to be Nicole’s biggest adversaries, judgmentally weaving a “how can we top that last terrible heartbreak for this evil woman who committed paltry crimes at best?” Horrific enough that she went through the tragedy of losing a baby once, but to push her into repeating that trauma in an astonishingly grotesque manner seemed much uncalled for and heinous. They made an example of out this Mary Magdalene pariah, promising miraculous motherhood twice and ripping it from her grasp, a condemnation for her tumultuously stormy past.

Nicole had changed an independent streak of fine drinks, men, and expense into fantasies of picket fences, mounted family picture frames, and false love–that is the fairy tale life every woman truly wants at the end of the day, right?

No. That cannot be farther from the truth.

There was always something amazingly addictive about spirited Nicole. She reveled in her own world, cared little for how others viewed her, and wasn’t hung up on family life until those two pregnancies came and went. Sure, she had been intimate with men she didn’t love, but it was hard swallowing her need to be an instant Kodak moment package deal to someone.

In one o’clock hourglass hour, Nicole is a cold, calculating vixen that viewers love to hate, but Zucker plays Nicole so ruthlessly, with so much fire and passion that it is virtually impossible to despise her forever.

|

| Under God’s “roof,” Nicole (Arianne Zucker) is on her best behavior. |

However, nowadays, Nicole Walker is a little different. Not quite a shell of her former self, she still has that witty humor and vivacious spark, but those two pregnancies, especially the last, have robbed her of a certain edgy caliber and transformed her into a woman attempting to be a good heroine for her latest desire–Father Eric Brady, Samantha’s twin brother (pattern? yes!). Underneath the surface of this seemingly reformed church secretary lie buried schemes, nasty wordplay, and wicked fantasies, but she has turned over a whole new leaf.

For now.