This guest post by Nicole Elwell appears as part of our theme week on Child and Teenage Girl Protagonists.

The CW is a rarity among the many networks of cable television. Its target demographic is women aged 18-34, and as a result has a majority of its original programming centered on the lives of young women. On paper, this sounds like a noteworthy achievement to be celebrated. However, the CW produces content devoid of any sense of the reality of its young audience, and as a result actually harms its most devoted viewers. The CW creates an unattainable archetype for what a teenager should look like and fails to maturely handle issues of murder and rape.

Despite the assertion that the CW’s programming is for adults aged 18-34, one look into the fervent fan bases of shows such as The Vampire Diaries suggests that audiences can be much younger.

This makes sense when considering that the majority of the CW’s most popular programs are about teenagers. Because of this, it can be assumed that the basic plotlines of the CW’s best performing programs reflect what the network believes young women desire in a television show. IMDb describes The Vampire Diaries’ plot as “a high school girl is torn between two vampire brothers.” Newcomer Reign is gifted with the lengthy description: “chronicles the rise to power of Mary Queen of Scots when she arrives in France as a 15-year-old, betrothed to Prince Francis, and with her three best friends as ladies-in-waiting. It details the secret history of survival at French Court amidst fierce foes, dark forces, and a world of sexual intrigue.”

These simplistic plots offer a glimpse into the mindset of a network that claims to understand its audience: young women don’t want realism in their television but rather escapism into epic love triangles and even more love triangles amidst “dark forces.” Not to say that some young women don’t enjoy these themes (as is clear with the popularity of these shows), or that escapist television is wrong or harmful, but the CW has a habit of repeating its content due to popularity (perhaps the best example being the lovechildren of The Vampire Diaries, The Secret Circle and The Originals). When the same formula is used again and again, it becomes the norm and hurts both the audience and the network. Even the most far-fetching escapist stories need some base of reality in order to connect with a human audience, and the CW struggles with this. Because of its image to serve everyone’s inner teen, the CW’s content is also implicative of what teens actually want in their television. When looking at the basic plots of the CW’s programs, it can be established that female teen audiences want sensationalized love affairs and no substance.

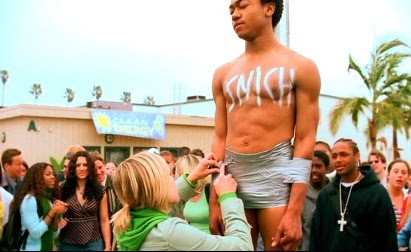

The stereotyping of a young female audience isn’t even the CW’s biggest problem. The major problem is that the CW makes programs for a younger audience, but doesn’t understand the reality of their audience. According to the CW, an average teenage girl and boy should look something like this:

This is not a problem specific to The Vampire Diaries. Any CW program that centers on the lives of teenagers casts 20-something or even 30-something actors to portray those roles. This creates a ridiculously unattainable archetype for both male and female teenagers to strive for. The inevitable inability to achieve televised perfection has the potential to damage self-esteem, confidence, and feelings of self-worth.

The sexualization of the teenagers in CW programming is also potentially damaging to a teenage audience. Despite my many years of viewership to programs on the CW, I never fully realized the extent to which perceived teenagers are sexualized on the network’s numerous shows. The realization came with one of the more recent episodes of CW’s newcomer Reign, which was recently picked up for a full season. The specific episode “Left Behind” involved Mary Queen of Scots’ home at the French castle under siege by a vengeful Italian who lost his son by French hands. After numerous episodes of love-triangle development, I felt I was finally getting what I came for with Reign–political plot lines and development into Mary Queen of Scots political history. Instead, I came to the realization that Reign has no intention of making Mary Queen of Scots anything more than an object of sexual desire. The show doesn’t even consider Mary exploring her sexuality, but has only shown others desiring her, and this fact coincides with her physical appearance. An opening scene in “Left Behind” shows Mary, the current queen of France, the current prince of France, and the one-dimensional vengeful Italian explaining his reasoning behind overtaking the French castle in the absence of the French king. The dress that Mary wears in this scene and throughout most of the episode, pictured below, is her most revealing dress to date and its distraction completely undermines both Mary’s character and the performance from actress Adelaide Kane.

This particular episode of Reign was also problematic because of its rape theme and the connection to Mary’s drastic wardrobe change. The sexualization of Mary and the threat of rape aren’t new to Reign, but it’s important to note the coincidence of Mary’s revealing dress and the presence of the one-dimensionally savage Italian army who attacks Mary and her friends with no motivation other than to be evil. When analyzing the implication of changing Mary’s wardrobe in this specific episode, it can be argued that “Left Behind” is supporting the claim that rape victims are in part responsible for their rapes because of the clothes they wear. Whether intended or not, these two aspects of Reign’s plot coming together is detrimental because it reduces Mary to a sexual object and wipes away the legitimate characteristics of intelligence and strength expressed in previous episodes. It is also suggestive of inaccurate and damaging misconceptions about rape.

The sexualiazation of female characters has become an expectation in nearly all CW programming. With a dominant female audience, this becomes a problem to younger viewers who see these unattainable bodies and sex-fueled plots become the norm. Shows like Reign and The Vampire Diaries have the gift of a strong female lead, but never use that gift to develop strong and meaningful plots around their characters. The CW uses teenagers as a focal point for so many of their shows, but continues to shy away from the reality of being a teenager and instead treats teenage characters like they’re adults. Themes of rape and murder are constantly one-episode plot devices and never feel significant to the characters or to the audience. The CW’s audience isn’t made up of teens alone, but those 18 and under who do commit hours to their programs are receiving damaging subliminal messages about body image and issues of rape and murder. The CW has come to expect the impossible from its male and female characters: all must have flawless beauty, an acceptance and forgiveness of murder, and emotional strength that stems from accepting a dire situation rather than fighting against it. The audience who witnesses this same formula is expected to accept these terms as well. But it’s just not reality.

Nicole Elwell is a sophomore at the University of Baltimore, majoring in Psychology and minoring in Pop Culture. She hopes to bring psychology and feminism into a future career in writing for the movies.