This post by staff writer Sarah Smyth appears as part of our theme week on Unlikable Women.

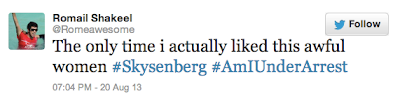

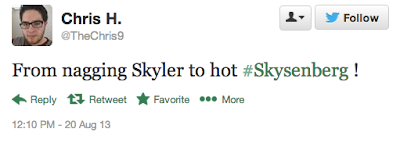

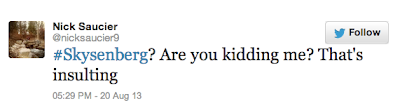

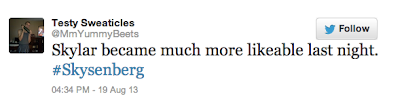

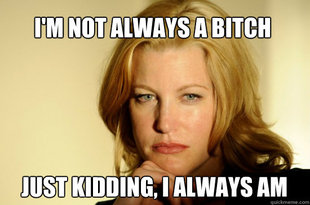

In the proclaimed “golden age of television,” female characters, it seem, get a pretty raw deal. Not only is there a lack of female-driven shows (or, perhaps more accurately, a lack of critical consensus surrounding female driven shows), but there’s also a keen hatred towards any female characters deemed “unlikable.” Take, for example, Breaking Bad. Despite Walter White becoming a drug kingpin, murderer, and rapist, Skyler, his wife, elicited a vitriolic response from the audience. Most worryingly, as the actress who played Skyler, Anna Gunn, noted, this response was deeply rooted in sexism and misogyny: “I finally realized that most people’s hatred of Skyler had little to do with me and a lot to do with their own perception of women and wives. Because Skyler didn’t conform to a comfortable ideal of the archetypical female, she had become a kind of Rorschach test for society, a measure of our attitudes toward gender.”

Aside from the deeply troubling attitudes toward “unlikable” female characters from the audience, another problem we encounter when attempting to examine “unlikable” female characters is the programme’s lack of detailed, nuanced and critical explorations and examinations of these characters. Returning to the problem of Skyler, Bitch Media’s Megan Cox puts it neatly: “While the show revolves around Walt’s struggles along the spectrum of morality, Skyler never gets much space to be an independent character. Her story really revolves around the choices her husband makes. It’s hard to build empathy with a character whose internal conflicts are never fully explored—instead, she often seems to just be getting in the way of the story, as another obstacle for her husband.”

What exactly, then, makes a character “unlikable”? How can we define this complex term? Broadly, a character is unlikable when they behave in an amoral or unethical way (which, of course, depends upon our individual morals and ethics), particularly when their motivations are unclear. However, when it comes to female characters, this term seems to diversify and pluralize. With a strict code of behaviour, even in the Western world, women can be more easily identified as “unlikable.” We’re supposed to dress in a certain way. We’re supposed to behave in a certain way. We’re supposed to be excellent partners, mothers, daughters, sisters, and friends. We’re supposed to have a “hot” body. We’re supposed to be sexy but never sexual ourselves. We’re supposed to be strong but not too strong, ambitious but not too ambitious, smart but not too smart. We’re supposed to be pleasing, pretty and altogether agreeable. And we’re supposed to have a sense of humour about the whole darn thing. Any departure from these set of expectations and we risk being marked as a deviant, a failure, a thoroughly unlikeable woman.

In Mad Men, Peggy Olson is often constructed- and construed, both by other characters and the audience – as “unlikable.” Introduced on the show as Don Draper’s secretary at advertising powerhouse, Sterling Cooper, she goes on to develop a hugely successful career as a copywriter, breaking several glass ceilings along the way. What is notable about her character, particularly in the early seasons, is the way in which Peggy fails – or refuses – to exploit her sexuality in the workplace. Unlike the other secretaries in the office, she fails to look sexy or even stylish. This is particularly crystallised in the pilot episode, “Smoke gets in your eyes,” when Peggy is mocked by her colleagues, Pete Campell and Joan Holloway, for her dowdy dress sense. As the show progresses, however, it is clear that Peggy will not play by the rules of the blatantly sexist workplace, rules which, as Joan demonstrates, the women clearly internalise. There is only one notable moment when Peggy attempts to “sex up” her look. In a season two’s episode, “Maidenform,” Peggy finally takes Joan’s advice to “stop dressing like a little girl,” and goes to the strip club where her (male) colleagues are enjoying a sleazy night with their account, Playtex, dressed in a revealing outfit. However, what’s clear is that Peggy refuses to do so in order to make herself appealing to men. Earlier in the episode, the boys mock her in a meeting for being neither Jackie or Marilyn but Gertrude Stein. Peggy retorts that she’s neither Jackie nor Marilyn because she refuses to be categorised by their male world. By boldly defying rigid and narrow expectations of femininity, and by displaying her sexuality only when its on her terms, Peggy not only retains a level of control and autonomy that was rare in the 1960s. More crucially, she refuses to be perceived as attractive, appealing or likable for her male colleagues.

For the audience, however, this may not make her character “unlikable” as such. In fact, this kind of badassery is exactly the kind of thing which earns Peggy a worshipping Buzzfeed article. What becomes more troubling – and, arguably, unlikable – is the development of her character, particularly in the later seasons. Peggy becomes bitter, harsh and critical, particularly towards her colleagues. Seemingly disillusioned with her career, she becomes a harsh task master, and lacks any sense of humour in the office or outside of it. Her already “outsiderness” from being a woman intensifies as her hostile attitude fractures her relationships with her colleagues further. As James Poniewozik in Time puts it: “Where have you hidden our Peggy, Mad Men? And how did you replace her with this hostile, unpleasant basket case, lashing out at everyone in sight and pining over a long-lost married man [Ted, an older married man who also happens to be her boss]?”

Poniewozik suggests that Peggy’s unlikability both from the audience and from the other characters on the show is precisely down to the show’s writing: “The problem here is that right now Angry Lovelorn Peggy is all the show is giving us. Right now, though, the balance [between her personal and professional life] seems badly off; what we see of Peggy at the office is refracted almost entirely through reminders that she’s shattered over Ted to the point of seeming like a different person… It isn’t about the show being obligated to make Peggy perfectly likeable, or empowered, or happy. It is about maintaining the complexity of a character who, over six seasons, has become the de facto female lead; or, at least, if her character radically changes, providing a reason beyond, ‘She went through a really bad breakup last season.’”

In one particular episode, “A Day’s Work,” Peggy mistakes flowers sent to her assistant, Shirley as her own. Thinking they were from Ted, she spends the day fretting over them before throwing them out and leaving an abrupt message for Ted with his assistant. When Shirley finally reveals who they were actually intended for, Peggy, angry and embarrassed, demands a new secretary. Peggy is presented as petty, selfish, and thoroughly unlikable. This is magnified later in the episode as her demands for a new secretary results in Dawn, a Black woman, being assigned as the new receptionist, something which the firm’s partner, Bert Cooper objects to purely on racist grounds. In this moment, Peggy fails to recognise both her privilege at being white within the working world. But, more crucially, she fails to recognise and empathise with someone who faces disadvantages and obstacles in the workplace, something she faced only a few years previously.

However, we may judge, pity, and despise female characters like Peggy, but we must always triumph them. For as long as we have “unlikable” woman – well-developed, nuanced, and centralised woman, particularly on television – we not only defy highly gendered codes and expectations and triumph deviancy. We can also further gains toward producing characters as complex, multifaceted, and unlikable as male characters.