This guest post by Sarah Stringer appears as part of our theme week on Child and Teenage Girl Protagonists.

The opening monologue of Veronica Mars makes it sound like this show is going to stick very closely to the trope of the jaded heroine, whose job has shown her so much lying and cheating that she’s closed off to the possibility of relationships. This idea is reinforced throughout the show, as various characters make jokes about Veronica’s cold cynicism. She’s snarky and sarcastic, and does have trouble getting close to people, largely because of all the trauma she went through before the beginning of the show.

However, Veronica Mars ends up subverting our expectations. Far from being a show about an aloof hero who can’t work with others, it ends up being largely about Veronica’s various relationships. It’s a running joke throughout the show that she’s constantly asking her friends for favours, but it’s also a running joke that people are constantly asking Veronica for favours, and the favours she asks for are usually to help her help others.

Her friends complain about constantly having to come to her aid, but they never refuse her requests, because they know the favours will be returned when they’re in need. This creates complications, as Veronica finds the line between relationships based on mutual usefulness and reciprocity, and relationships built on genuine caring and respect. As the first couple of seasons progress, she gets better at navigating the second kind of relationship, and mixing it with the first kind.

It’s common wisdom that maintaining relationships requires constant work, but there’s often an assumption (in TV, movies, and real life) that this only applies to romantic relationships. Platonic relationships are rarely the focus of a story, and when a storyline deals with issues in these relationships, they’re often easily dealt with, and the friendship goes back to being simple. Exceptions to this are problems that are caused by romantic relationships. Veronica Mars is an exception to this; for its first two seasons, it depicts many platonic relationships, and explores the many issues involved in navigating them (some of these problems are related to romance, but many are not, showing platonic relationships have their own complexities, separate from romance).

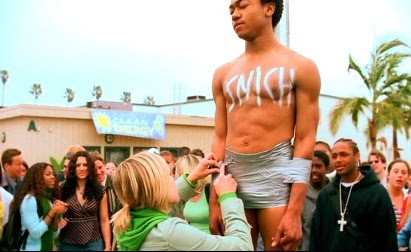

Veronica starts season one with no friends, but in the pilot episode, she befriends the new kid at school, Wallace Fennel. Her very first meeting with him involves her helping him out, by cutting him down from the flagpole where some bullies had duct taped him. She immediately lets him know that sitting with her won’t help his social standing, and he doesn’t need to be her friend just to reciprocate her gesture. He sits with her anyway, not because he feels like he owes her for the help, but because he likes her as a person.

Wallace and Veronica become best friends, and they’re a rare example of a show seriously dealing with the complexities of platonic relationships. As Wallace spends more time at the school, he starts to befriend other students, and get quite popular as a result of being a star on the basketball team. This creates problems in his relationship with Veronica, as they both try to navigate the jealousy, resentment, and time conflicts that come from vastly different social statures.

Another issue in Veronica’s relationship with Wallace is the same issue that exists in all her relationships: the balance between genuine friendship and trading of favours. She often uses his job in the school’s office to get information for her cases, and he’s put himself at risk in that way and other ways to help her. He grants all her requests, sometimes with no knowledge of why he’s doing it (and no questions asked), but he knows her resources will be put to his use anytime he’s in trouble.

Sometimes the balance starts to tip too far, and Wallace feels like she’s taking him for granted. This comes to a head several times, especially when his mother gets in trouble at her job because of something Veronica had him do, without telling him how dangerous it could be. He calls her out several times when she starts neglecting her friendship with him, blowing him off to work on her cases and just using him for the assistance he offers. Veronica tries to make up for this by doing things like baking spirit cookies for his locker, telling him she may have no school spirit but he does, and what’s important to him is important to her.

The issue of one partner taking the other partner for granted is one that often comes up in relationships, and little gestures to show affection is a common (partial) solution to it. The depiction of this as a constant issue between two platonic partners is quite refreshing.

This dynamic is seen in several of Veronica’s other relationships, particular with Weevil, a local biker, and Mac, a computer nerd. She gets Weevil and Mac out of trouble when they need it, and they both help her out whenever they can. Working around the inherent potential for taking advantage of each other, as well as Veronica’s own cynicism, they forge genuine friendships that grow as much as any romantic relationship.

The show also devotes a lot of time to Veronica’s relationship with her father, Keith. She works for him at his private investigator practice, and there are times when it’s difficult for them to navigate the dual dynamics of father-daughter and detective-receptionist/junior detective. He wants to protect her, but also teach her, and he often needs her help. He wants to trust her, but there are times when she breaks that trust, and he has to decide how to deal with that as a father and as a boss.

Familial relationships aren’t rare in television or movies (though complex portrayals of them are still rarer than in-depth looks at romance), but they’re rarely dived into as deeply as with Veronica and her father. They joke together, work together, go through extremely difficult circumstances together, and work together to come back from the problems created when they both inevitably screw up.

Veronica Mars portrays all these relationships, and their various issues, without touching romance. That’s not even getting into the relationships Veronica forms with whatever classmate she’s trying to help that week, or with other characters like Meg (her romantic rival, but also far more than that) and her dead best friend, Lily. In a subversion of a heroine who’s closed off and can’t get close to people, Veronica Mars is essentially a show about relationships of all types, and it’s at its best when it’s focusing on those.

The show deteriorated for many reasons in season three, but in my opinion, the major reason was the increased focus on romantic drama, at the expense of the many platonic relationships it built up previously. Weevil and Wallace have significantly smaller roles. Keith and Mac are still important, but mostly because of their own storylines, and they do a lot less interacting with Veronica. When Mac does talk to Veronica, it’s mostly so they can discuss their romantic lives, rather than develop their relationship with each other.

Romance certainly existed in the show before season three. Veronica had three boyfriends in two seasons, and those relationships were in no way simple or small parts of the story. But they were portrayed quite similarly to the platonic relationships: the focus was on human interactions, and two people figuring out how to fit their personalities together. They even shared the issues about genuine caring versus using each other; Veronica’s first boyfriend was a cop who she met because she was trying to sneak past him to steal evidence, and she spent the better part of the second season trying to get her next boyfriend off for murder.

However, in the third season, most of Veronica’s romantic issues were more superficial. Her and her on-and-off boyfriend Logan spent more moping about each other than actually figuring out how to be together (or not be together). There’s drama about who’s sleeping with who that leads to more fights than resolutions. The show seems to lose its focus, particularly since so many of Veronica’s platonic relationships are neglected.

There were things I liked about the third season of Veronica Mars, and I await the upcoming movie with as much bated breath as the next fan. But I hope the movie put the focus back where I think it belongs: on complex relationships of all kinds, rather than romantic drama.

See also at Bitch Flicks: “Why Veronica Mars is Still Awesome,” by Amanda Rodriguez

Sarah Stringer is a psychology student in Ontario, with an interest in the political aspects of pop culture.