This is a guest review by Lesley Jenike.

———-

I saw Terrance Malick’s The Tree of Life in a tiny, packed theatre in my hometown on my birthday last year. Of course I’d read around about the film before going to see it, and I fully anticipated its more “controversial” elements, but I wasn’t really prepared for the experience itself—the frankly theatrical experience of sitting in a dark room with a bunch of strangers who simultaneously felt (I imagine) a strange mixture of joy, embarrassment, frustration, and awe. People walked out. I heard someone whisper to his friend, “Oh my God.” Someone else laughed quietly to herself when the first dinosaur ambled onto the screen. But those of us who stayed left the theatre 139 minutes later dazed and puzzled, but weirdly connected to one another; I don’t doubt we all saw some of ourselves in the film. I even furtively searched faces for any discernable response, as if to ask in a Malick-like subconscious whisper, “What was that?”

Yes, what is The Tree of Life? Well, it’s a movie, a great movie that fully embraces its own nostalgia. It’s a movie that presents its narrative as only movies can: through exquisite mis-én-scene and shrewd editing. You see, the Tree of Life doesn’t try to wow us with jarring, frenzied cuts, nor does it present shocking images meant to scandalize and titillate. On the contrary, many of the images you’ll find in the Tree of Life are so familiar they become new again, thanks to context and Malick’s wholly realized filmic world. The real genius of Tree of Life is its complete and utter mastery over its own medium—and that may very well be the reason for all the hoopla. By cinematically juxtaposing two modes of discourse that rarely meet except in conflict—the scientific and the spiritual—Malick has created for posterity a years-in-the-making meditation on the very nature of existence. Whoa.

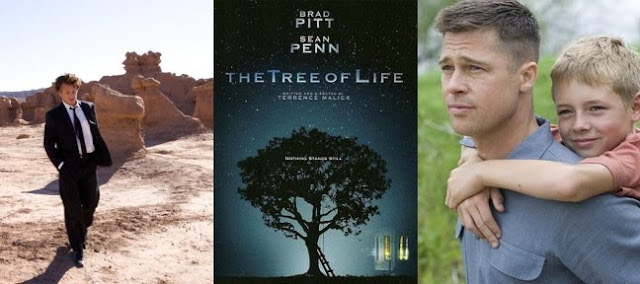

We begin with a quote from the Book of Job, a breathy voiceover, and, at the darkened screen’s center, a single sliver of light. And then—oh and then—image after image washes over us, sensual and earthy, specific yet universal, while a female voice—a voice we connect with a redheaded child who soon morphs into a bereaved mother grieving a son lost to the war in Vietnam—talks to us about the difference between “nature” and “grace,” a philosophical dichotomy that operates as the film’s central conflict. Mr. O’Brien (Brad Pitt) seems to represent “nature” in the Darwinian sense. His drive to survive and succeed causes him to behave (often without intention) cruelly toward his family. Mrs. O’Brien (Jessica Chastain), on the other hand, represents “grace,” or a sense of humility and kindness derived from a spirituality that, in Malick’s world, seems to operate beyond organized religion.

“Grace” is represented in the film as a sense of interconnectedness and empathy. In other words, Mrs. O’Brien is more of a quality than a character, a sort of angel whose sensitivity as a woman and mother seems almost otherworldly. While I’m perfectly prepared to call out Malick for inventing an unrealistic, two-dimensional, adolescent’s dream of a mother in Mrs. O’Brien, I must stress how specific the film’s point of view is and how completely invested we are as viewers in the oldest son’s (Jack, played as boy by Hunter McCracken and as an adult by Sean Penn) subjective perspective. We can feel the grass on our own hands when he touches it and we get a shiver of pleasure when he’s tucked safely in bed at night and his mother switches off the bedside lamp. If Mrs. O’Brien is a romantic ideal, it’s because Jack sees her that way. She even floats in the air at one point, her skirt billowing in the wind like the ever-present, rustling curtains we see in shot after shot.

Mr. O’Brien, on the other hand, looms as the big Other, creating law and doling out punishment; even his predilection for classical music suggests the very soundtrack of the O’Brien boys’ collective childhood is both beautiful and aggressive, tender and menacing. However, once Jack is aware of his father’s humanity and we begin to see Mr. O’Brien’s suffering through Jack’s eyes, Mr. O’Brien (beautifully played by Pitt) develops as a character despite few conventional, dialogue-heavy scenes. His past actions, like the harsh play-boxing match with his two older sons, is re-contextualized to suggest his cruelty doesn’t come from malice, but rather from his own pain and disappointment.

So what does this mean—a sorrowful, transcendent Madonna for a mother and a real human being for a father? Malick has given us a boy’s life and boys, in Malick’s world, must go the way of “nature.” Their propensity for violence and cruelty is discovered in their play, mirrored by the natural world, and ultimately enacted in war and in the workplace. Once their fall from “grace” is complete, they look back at their innocence with nostalgia, regret, and pain, idealizing their mothers and recognizing in themselves the foibles of their fathers. I saw much of my own childhood in The Tree of Life, but ultimately it’s a boy’s world, and Malick suggests a boy can never fully know the female “other.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself. All of the above hinges on the adult Jack O’Brien’s (Sean Penn) portions of the film in which he wanders through some random city’s steel and glass and contemplates his brother’s senseless death, as if trying—even in Earth’s chaotic, violent beginnings–to understand the nature of his own life and the lives of his family members. Where did he go wrong? Can he pinpoint the moment he betrayed his brother’s trust or turned his back on his mother’s “grace?” In Jack’s mental wanderings, we sometimes alight on some semi-relevant information (he’s breaking-up with his significant other; he’s done well for himself career-wise), but mainly we follow him through his own personal symbology (a Gulf Coast beach for a kind of Heaven; an underwater door meaning birth). These sequences are stunningly beautiful and terribly confusing at turns, but the truly ambitious cinematic move on Malick’s part is the lengthy sequence of cosmic configurations, interstellar explosions, and hot lava that finally create life. Life then becomes two dinosaurs in a riverbed that in their Darwinian struggle to survive, later mirror Jack and his younger brother who roughhouse down by what we take to be the very same river. In Malick’s contemporary worldview, a nebulous sense of spirituality rubs elbows with science’s rational explanation for creation, and this convergence is honest, weird, and often hard to reconcile.

I could spend pages on the folly of Malick’s choices here, but he’s embraced the totality of his medium so completely, he reintroduces us to what film is capable of in all its overwhelming, destructive glory.

———-

Lesley Jenike received her PhD from the University of Cincinnati in 2008. She currently teaches poetry writing, screenwriting, and literature classes at the Columbus College of Art and Design. Her book of poems is Ghost of Fashion (CustomWords, 2009).