Tag: Television

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Xander Harris: Hyena Boy

|

| Xander Harris (Nicholas Brendon) in Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

Guest post written by Monika Bartyzel originally published at The Hooded Utilitarian. Cross-posted with permission.

|

| Xander possessed by a hyena spirit |

|

| Xander and Buffy |

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Are You Ready to Be Strong? Power and Sisterhood in ‘Buffy’

|

| Buffy Summers (Sarah Michelle Gellar) in Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

No one will argue that the television show Buffy the Vampire Slayer isn’t populated with strong female characters. Buffy’s best friend, Willow, is a computer-hacking lesbian witch with the magical prowess to end the world. Her sister, Dawn, is a mythic Key who can open gateways between dimensions. Faith, Buffy’s sometime friend and ally, is a sexually and physically empowered slayer who revels in her body’s physical gifts. The female villains are also intensely powerful and iconic, ranging from ancient vampires, werewolves, and vengeance demons to genius scientists and even the ultimate foe, The First (though technically genderless, this force often takes the form of Buffy herself). Season 5’s villainess, Glory, is even a goddess whose power is only diminished when she is forced to inhabit the body of a human male, and if that ain’t feminist commentary, I don’t know what is.

|

| “The proverbial scales must balance. In order to restore the lives of the victims, the fates require a sacrifice: the life and soul of a vengeance demon.” – D’Hoffryn | Image of Anya |

|

| “There’s only supposed to be one. Maybe that’s why you and I can never get along. We’re not supposed to exist together.”- Faith | Image of Buffy (Sarah Michelle Gellar) and Faith (Eliza Dushku) |

|

| “This is the work that I have to do.” – Buffy | Illustration by boo21190 via deviantart.com |

“So here’s the part where you make a choice. What if you could have that power, now? In every generation, one slayer is born, because a bunch of men who died thousands of years ago made up that rule. They were powerful men. This woman is more powerful than all of them combined. So I say we change the rule. I say my power, should be our power. Tomorrow, Willow will use the essence of this scythe to change our destiny. From now on, every girl in the world who might be a slayer, will be a slayer. Every girl who could have the power, will have the power. Can stand up, will stand up. Slayers, every one of us. Make your choice. Are you ready to be strong?” — Buffy

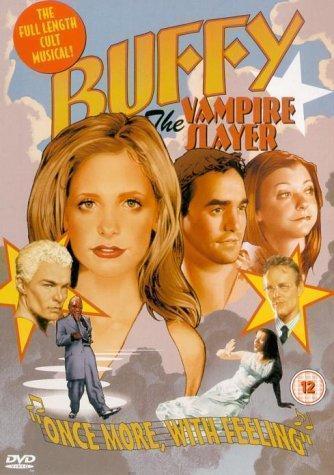

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Buffy Kicks Ass

|

| Buffy Summers (Sarah Michelle Gellar) in Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

“Yes, date. And shop and hang out and go to school and save the world from unspeakable demons. You know, I wanna do girlie stuff.” ~ Buffy Summers

Let us now discuss the epic feminist awesomeness that is Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer is exactly what it sounds like: A girl, named Buffy Summers, slays vampires and demons and wages war against evil supernatural forces. The major complicating factor? She’s a blonde, fashion-and-boy-obsessed California high school student who becomes a social outcast because of her secret identity and nighttime activities.

But first, a short personal history lesson:

One fall night in sixth grade, my B.F.F. Marcella came over after swim practice. She made a big stink about watching Buffy that night, since it was the second season premiere. I was reluctant to watch, as up to that point fantasy/horror hybrids were really not my thing (I was still in a lengthy L.M. Montgomery phase). However, Marcella sat my ass down and made me watch it. It was love at first (I’m so sorry) … bite.

In middle school Marcella and I used Buffy to cement our friendship. It held through attending separate high schools and my yearlong absence while I was an exchange student in Australia. We religiously analyzed last night’s Buffy episode every Wednesday at lunch. I had a buff-colored kitten named Buffy, and Marcella had a black kitten named Angel (after Buffy’s vampire-with-a-soul boyfriend). Marcella got all the DVDs as soon as they came out, and we would often soothe our teenage angst (break-ups, placing badly in the state water polo tournament, rejection by our first-choice colleges, etc.) with mochas and Buffy marathons. It became a common language of cultural and fashion references that were always fodder for conversation (and often girlish shrieking). When our other commonalities fell away as we grew up and away from each other,

Buffy kept us together.

But I digress.

|

| Buffy created by Joss Whedon |

The coolest thing about Buffy is that creator Joss Whedon conceptualized the show as a deliberate inversion of horror movie clichés. In traditional horror, when the girl wanders into a dark ally the audience expects her to meet a horrible fate. On Buffy, the girl hunts the monster in that ally, and then fights and defeats it. Whedon purposely created the show as a way to subvert and redefine the audience’s expectations about women.

The show layered this feminist perspective upon a strong tradition of high school and coming-of-age-stories in American pop culture. “In Buffy‘s world, by contrast, the problems teenagers face become literal monsters,” Rhonda Wilcox wrote in an essay in the Journal of Popular Film and Television. “Internet predators are demons; drink-doctoring frat boys have sold their souls for success in the business world; a girl who has sex with even the nicest-seeming male discovers that he afterwards becomes a monster.”

There is a lot of scholarly research and criticism of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. There’s a Wikipedia page dedicated to “Buffy Studies.” There’s even an academic journal called Slayage: The Journal of the Whedon Studies Association. No, I’m not kidding. The show has become a bit of a zeitgeist for feminist criticism, in particular for scholars interested in Third Wave Feminism.

And then, of course, Buffy kicked a lot of ass. A very serious amount of ass. Over the course of the show’s seven television seasons, she averted multiple apocalypses. She punned and killed all very large monsters and vampires that she came across. She added clever insult to injury. She never apologized for not being a dumb, weak girl. And it was very physical — in the canon of the show, a Slayer is given extra-human powers of strength, speed and agility. She was a fashionable girl’s girl, and she slayed creatures that go bump in the night. It was Girl Power at its late-1990s peak and taken to an excellent extreme.

|

| Buffy Summers (Sarah Michelle Gellar) |

Buffy deals with homework, dating and a single mother who’s just a bit clueless. Despite being labeled a loser, she navigates the social hierarchy of high school with her friends who assist in her fight against the undead. She goes through the many painful stages of sexual initiation and maturity. She fights the good fight of college admission, and later the decision to drop out of school when her mother dies and she must take care of a younger sister. She makes mistakes, and fails sometimes. While Buffy’s circumstances were different, they embodied situations and emotions I often felt as an adolescent trying to make my own way.

Buffy was not just a warrior, but a leader. Less than half way through the series, she quit taking orders from the Watcher’s Council, an ancient group of British people who identify and train the Slayer, and decides to go it alone with her friends. While Buffy defers research to her Watcher (who was fired from the Council) and friends Willow and Xander, she is the member of the darkness-battling team that makes, coordinates and executes the final plan. She essentially becomes the general of a guerrilla army, which becomes a more and more literal role as the series progresses.

Buffy is a hero. She has a destiny. She fought and died (twice). She saved the world a lot. And yet, the show wasn’t really about Buffy’s sacred duty to fight things that go bump in the night. It was, at it’s core, about how to deal with and survive the pressures of being a young woman in American society.

|

| Buffy |

And, hot damn, the girl looked good doing it. In the tradition of WB teen show characters dressing like they had unlimited budgets and stylists, Buffy had the BEST clothes. Well, for 1997-1999, she had the BEST clothes. If there was ever a fashion icon Marcella and I strove to emulate, it was Buffy. Her very short skirts, leather pants, spaghetti strap tank tops and platform boots were the holy grail of sartorial achievement in middle school (mostly because we had to fight our mothers to be allowed to leave the house dressed in them). Buffy rocked super-feminine styles tempered by leather, denim and practical pieces. While most of her wardrobe is horrifying in retrospect, there are still a few items I’d wear and rock the shit out of today.

In the first season finale, Buffy accessorizes a white satin and chiffon prom dress with a black leather jacket and a crossbow. Fashion doesn’t get more bad-ass than that.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer is a concept that could and did go terribly wrong. Its first incarnation, a 1992 movie of the same name, is awful. Yet the film showed signs of brilliance nonetheless. The TV show rectified all the problems of the movie, by making the fictional universe and characters deeper, wider, darker and much more interesting. The show wouldn’t have been such a phenomenon if it were crap. It really is excellent television on all levels. The writing was clever and intelligent without being preachy, the characters were real, and the action was fantastic. It is really fun to watch. Joss Whedon is a singular talent—he really can do no wrong. He loves super-powered women, and that shows in all aspects of his storytelling.

Looking back, I honestly believe that Buffy had a profound effect on my own development as a feminist thinker. At the time, I was just watching a cool show with fun dialogue, tragic romance and drool-worthy shoes. But I internalized a lot of the subtext and it helped shaped how I view modern womanhood: A girl can kick ass, and look pretty doing it.

Erin K. O’Neill is an award-winning writer, photographer, visual editor, and digital marketing professional currently located in her hometown of Ann Arbor, Michigan. A devotee of literature, photography, existentialism, and all things Australian, Erin also watches too much television on DVD and Netflix. Follow her on Twitter, @ekoneill.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Buffyverse Season 2 Trailer

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: The View from the Grave: Buffy as Gothic Feminist

|

| Buffy Summers (Sarah Michelle Gellar) in Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

Guest post written by Jennifer M. Santos.

|

| Buffy in the series finale |

|

| Buffy and Spike |

Jennifer M. Santos has taken a break from professoring to do more writing about fun, feisty females. When she’s not writing about Buffy or Lady Gaga, she’s using her Ph.D. in English to unearth nineteenth century vampires. And when when’s not doing that, she continues the never-ending battle to convince her cats that she’s the alpha.

Buffy Week: The Incoherent Metaphysics of the Buffyverse

Buffy the Vampire Slayer was famously asking the question: what if, in a typical horror-movie monster-chases-girl scenario, the girl turned around and kicked the monster’s ass? But it’s also, perhaps less wittingly, asking the question: what happens when an atheist – someone who disavows the existence of all things super- or preternatural in the real world – writes a show about the supernatural?

|

| Come on, it’s a bit silly. |

|

| This is… what a soul looks like? |

|

| But also, there were really really awesome things. |

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: A Love Letter to Buffy: How the Vampire Slayer Turned This Girl into a Feminist

|

| Buffy Summers (Sarah Michelle Gellar); Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

Guest post written by Talia Liben Yarmush originally published at The Accidental Typist. Cross-posted with permission.

|

| Buffy cast |

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Buffyverse Season 1 Trailer

‘True Blood’ Asserts a Pro-Choice Reproductive Rights Message

“No. We procreate because we want to. Not because some dickhead dipped in afterbirth told us to.”

“We’re not running. No one fucks with us in our house.”

“They can both keep their fucking laws off my body.”

“No, they can do whatever they want with your body.”

A Feminist Look at The Women of ‘Arrested Development’

The fourth season of Arrested Development is in production, and fans are blueing themselves in delight. Every time I turn around, entertainment news is buzzing with more information about the show’s upcoming revival. Right after we fans calm down over our initial excitement at seeing Jason Bateman’s tweet of the first set photos, we hear more good news from David Cross as he hints at a longer season than originally planned.

|

|||

| Lucille Bluth (Jessica Walter) and the wink that makes her son uncomfortable |

|

| Lindsay Funke (Portia de Rossi) in her infamous Slut shirt |

|

| Maeby is confused, and not impressed. |

Maeby has a complicated relationship with her mother. While Lindsay often seeks Lucille’s approval only to get smacked down and criticized, Maeby tries to get any kind of attention (mostly negative) from her mother only to be ignored. In fact, Maeby is often overlooked and ignored by most of the members of the Bluth-Funke family – except for her cousin George Michael, who’s in love with her. This neglect leaves Maeby free to do whatever she wants, whether it’s skipping school, breaking into offices to steal evidence for her grandfather, or bluffing her way into the position of movie executive while she’s still in high school.

Movie Riffing: A White Man’s World

|

| RiffTrax: funny white men. |

|

| MST3K / Cinematic Titanic: mostly funny white men. |

|

| OH MY GOD GIVE HER A SHOW ALREADY |