|

| Good God this man is terrifying. |

|

| Poor Nicola. |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Good God this man is terrifying. |

|

| Poor Nicola. |

|

| Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) in Terminator 2: Judgment Day |

This post previously appeared at Bitch Flicks on May 25, 2012.

Mothers are supposed to be everything to everyone. Sadly, society often stigmatizes, vilifies and demonizes single mothers. Single moms are blamed for “breeding more criminals.” Single parenthood is criminalized and “declared child abuse.” On top of that, “almost 70% of people believe single women raising children on their own is bad for society.” WTF? Seriously?? Wow. Way to be misogynistic people.

[…]

| Dr. Shaw, being serious |

| Jo Grant, being a nature child |

| Jo Grant is unimpressed by your gun, Master |

| Jamie McCrimmon does not know the meaning of personal space |

| Most of the Doctor’s companions, Old and New (if you don’t include non-televised media) |

|

| Cast of Firefly and Serenity |

Guest post written by Janyce Denise Glasper.

“Why do you keep writing strong female characters?”

“Because you’re still asking that question,” Joss Whedon quips.

|

| The women of Firefly and Serenity — L-R: Jewel Staite (Kaylee), Summer Glau (River), Morena Baccarin (Inara), Gina Torres (Zoe) |

|

| Zoe (Gina Torres) |

“Love. You can learn all the math in the ‘verse… but you take a boat in the air that you don’t love… she’ll shake you off just as sure as the turn of the worlds. Love keeps her in the air when she ought to fall down… tells you she’s hurting before she keels. Makes her a home.”

|

| Kaylee (Jewel Staite) |

|

| Inara (Morena Baccarin) |

Serenity means the state of being calm and untroubled — Inara Serra embodies the definition. The poised, tranquil companion, or in other words a courtesan, has illustrious skills beyond sensual grace. Softly spoken and wisely engaged, she battles with tongue more so than weapon. An expert with combat and a bow and arrow and often a vital aide in fighting the good fight, she gets knocked around a bit, but that doesn’t stop her from continuing to join in the battle of Malcolm verses The Operative, licking her wounds and going back for more to protect nearly brutally defeated captain.

|

| River (Summer Glau) |

|

| The women of Firefly and Serenity — L-R: Gina Torres, Summer Glau, Morena Baccarin, Jewel Staite |

|

| The cast of Battlestar Galactica |

|

| Willow Rosenberg (Alyson Hanigan) on Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

|

| Willow (Alyson Hannigan) talks to Buffy (Sarah Michelle Gellar) |

|

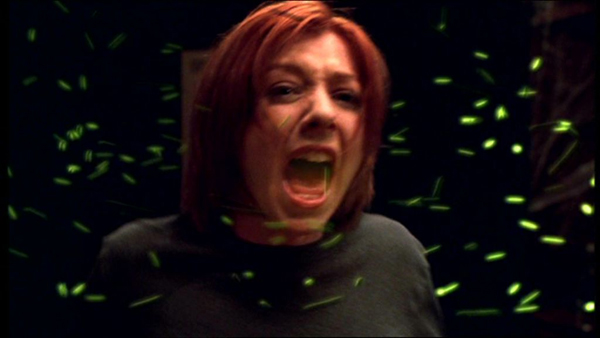

| Willow possessed as she performs the spell |

|

| Willow’s spell goes wrong |

|

| Dream-Willow delivering a book report |

|

| Willow talks to Buffy after coming down from a high |

|

| Olivia Dunham (Anna Torv) on Fringe |

She often puts herself in harm’s way to protect those around her and is willing to do anything necessary in the name of justice and fringe science (including having electrical equipment embedded in her skull and then being submerged in an isolation tank.

|

| Olivia Dunham (Anna Torv) on Fringe in isolation tank |

What I love most is her seemingly inability to be made vulnerable by villains. In several episodes she is rendered unconscious and kidnapped, however, she is hardly ever saved by other people. Although the other members of Fringe are looking for her, she’s the one to smash something against someone’s head or brandish a scalpel as a deadly weapon in order to escape. And it’s not that she busts down doors, guns blazing, but that she knows the appropriate time to do so, or when a lock pick and stealth will suffice.

|

| Olivia (Anna Torv) and Peter (Joshua Jackson) on Fringe |

|

| Olivia and Fauxlivia (both played by Anna Torv) on Fringe |

|

| Falling Skies‘ Margaret |

Guest post written by Paul and Renee.

The wonderful thing about science fiction is that the writers have the opportunity to create a world, which while based on ours, can be markedly different. This means that there should be a place for strong female characters who are not restricted by sexism or forced into a situation in which they must perform femininity on a daily basis to be accepted as ‘woman.’ Despite the freedom of this genre; however, nothing is born outside of discourse, which means of course that we end up with the same sexist tropes repeatedly.

|

| Sanctuary‘s Helen Magnus |

Even when we have strong female characters, they are still not free of damaging tropes. In Continuum, Kiera is strong and is proactive; each week she and her partner Carlos, take turns hunting down the bad guys. Keira is not afraid to get physical if she has to. That sounds great doesn’t it? It would be if that was all I had to say about her, but it seems that once again, a strong female character cannot just be strong. She has to have a vulnerable side and for Keira it’s motherhood. It makes sense that a mother living so far away from her child, would miss her son desperately, but it does not make sense that this sense of loss would turn into her deciding to lecture her grandmother into giving birth and rejecting every legitimate reason she had to have an abortion.

|

| Continuum‘s Kiera |

|

| Daniel Tosh |

Serious Trigger Warning for discussions of rape, rape culture, and sexual assault.

———-

Last Thursday, Megan wrote a piece about the recent Daniel Tosh clusterfuck–“Dear Daniel Tosh: You Know What’s Even Less Funny Than Rape Jokes? Rape Threats“–in which she discusses “his misogynistic douchebaggery as he verbally attacked a female audience member.”

She writes:

But just in case you haven’t [heard] or if you need a refresher, the woman called Tosh out amidst his performance at The Laugh Factory. Here’s what the woman told her friend who posted it on her blog which has now gone viral:

“So Tosh then starts making some very generalizing, declarative statements about rape jokes always being funny, how can a rape joke not be funny, rape is hilarious, etc. I don’t know why he was so repetitive about it but I felt provoked because I, for one, DON’T find them funny and never have. So I didnt appreciate Daniel Tosh (or anyone!) telling me I should find them funny. So I yelled out, “Actually, rape jokes are never funny!”

“I did it because, even though being “disruptive” is against my nature, I felt that sitting there and saying nothing, or leaving quietly, would have been against my values as a person and as a woman. I don’t sit there while someone tells me how I should feel about something as profound and damaging as rape.

“After I called out to him, Tosh paused for a moment. Then, he says, “Wouldn’t it be funny if that girl got raped by like, 5 guys right now? Like right now? What if a bunch of guys just raped her…”

Wow. What. The. Fuck. Rape jokes are never funny. Ever. Making a rape joke is bad enough. But attacking an audience member who calls bullshit on said rape joke?? Calling for her to be gang raped?? Horrifying and disgusting.

And we’ve noticed a few things here and there: rape being played for laughs in Observe and Report; the sexual trafficking of women used as a plot device in Taken; the constant dismemberment of women in movie posters; the damaging caricatures of women as sex objects in Black Snake Moan and The Social Network; and we’ve often pointed to discussions of sexism and misogyny around the net, like the sexual violence in Antichrist and, most recently, the sexualized corpses of women in Kanye West’s Monster video. It barely grazes the surface. I mean, it barely grazes the fucking surface of what a viewer sees during the commercial breaks of a 30-minute sitcom.

Yet, this constant, unchecked barrage of endless and obvious woman-hating undoubtedly contributes to the rape of women and girls.

The sudden idealization of Charlie Sheen as some bad boy to be envied, even though he has a violent history of beating up women, contributes to the rape of women and girls. Bills like H. R. 3 that seek to redefine rape and further the attack on women’s reproductive rights contributes to the rape of women and girls. Supposed liberal media personalities like Michael Moore and Keith Olbermann showing their support for Julian Assange by denigrating Assange’s alleged rape victims contributes to the rape of women and girls. The sexist commercials that advertisers pay millions of dollars to air on Super Bowl Sunday contribute to the rape of women and girls. And blaming Lara Logan for her gang rape by suggesting her attractiveness caused it, or the job was too dangerous for her, or she shouldn’t have been there in the first place, contributes to the rape of women and girls.

It contributes to rape because it normalizes violence against women. Men rape to control, to overpower, to humiliate, to reinforce the patriarchal structure. And the media, which is vastly controlled by men, participates in reproducing already existing prejudices and inequalities, rather than seeking to transform them.

And it pisses me off.

Allow me to add the Daniel Tosh Rape Threat Controversy to the list.

———-

Daniel Tosh Is a Rape Culture Enforcer by Melissa McEwan via Shakesville

There isn’t much I can say about this, at least nothing I haven’t already said literally hundreds of times before in every conceivable way I can imagine: Rape jokes are not funny. They potentially trigger survivors, and they uphold the rape culture. They tacitly convey approval of rape to rapists, who do not appreciate “rape irony.” There is no neutral in rape culture, and jokes that diminish or normalize rape empower rapists. Rape jokes are pro-rape.

Male Comics: Stop Enabling Rape Culture by Molly Jane Knefel via Salon

Indeed, like one of those terrifying millipedes, this controversy gave birth to a thousand little baby controversies once it was opened up. It has led to conversations about if and how rape jokes can ever be funny; it has illuminated Tosh’s history of laughing at violence against women; it has called attention to the horrifying statistic that one in four women has experienced sexual assault, and that those women are in the audiences of comedy shows. It’s made some question whether it is ever right — or only right — for women like Sarah Silverman to make these jokes. It has also prompted comics to defend satire, to defend setups, to explain why interrupting a comic mid-joke is disrespectful and to remember all the terrible things they have said to hecklers to shut them down. But there is one really important controversy that we cannot let get away from the comedians: Why are there so many rape jokes in the first place?

This is about whether comedy, and the world at large really, will allow women to push back against rape culture. This woman felt uncomfortable with Tosh’s rape comments because we live in a world where rape is expected, and she doesn’t find that funny. Tosh’s response, and the responses of his colleagues, aren’t about defending rape jokes—we live in a society where, unfortunately, they don’t need defending—they’re about shutting this woman up. They’re about maintaining the status quo—the one where men are allowed to rape women who talk back, who dress like sluts, who “ask for it”—at all costs, even if it means threatening someone with gang rape. If she tries to fight back then she just doesn’t get it. And if others call out this behavior, then they don’t get it either.

If this is what Tosh wanted to do artistically, then, well, he has every right as a comedian to do so. The fact that he backpedaled on the joke on twitter however suggests that he doesn’t want to be seen as that kind of comic. Again, Tosh wants to be liked. He wants to be popular, and so we circle back to the fact that the problem isn’t Daniel Tosh. The problem is that our society is still a rape culture where a large percentage of people think that rape’s OK and that a girl in a short skirt is asking for it and that it’s funny to assault someone. Not for the sake of satire, but for one person’s amusement over another person’s real life victimization.

Culture is why Tosh is just a symptom. He’s simply doing what works to generate a small fortune, capture six million Twitter followers and be a number one rated comedian. That’s why this isn’t a First Amendment problem but one of market demand. The First Amendment gives people the right to make rape jokes and this right is critical and non-negotiable. But, it doesn’t obligate comedians to tell these jokes, nor does it obligate others to pay to hear them because they find them entertaining. That’s a matter of our culture and what is considered the current norm for human decency and empathy. Tosh in this way is no different from Facebook – which chose to keep rape joke pages up (in violation of its own guidelines prohibiting hate speech, if they apply to women) but removed a picture of an asexualized woman walking down the street topless in NY for being obscene. I’m not letting him off the hook, though. He has no (meaningless) corporate guidelines to follow, but he has an ethical choice about the jokes he makes and how he makes them. Rape jokes aren’t simply R-rated antics.

Yes, many comedians take life’s tragedies and make fun of them; they use humor as a way of coping with the awful things that happen to people. It’s actually similar to my own defense that bringing the funny into feminism and social justice makes it all the more accessible and fun, and can be a way for us to collectively laugh at the injustice that we have to deal with on a daily basis.

What Tosh did was not that.

But would it be funny if this girl got gang raped right this moment, like right now right now? That’s not a joke. It’s an invitation. It’s a celebration of a violent crime, which is itself another violation. It’s not a way to cope. It’s a “this is something we can do and then laugh about it, no big deal.” When you reiterate these half-truths (there are girls in the world getting raped by like five guys right now), they authenticate themselves, as if by magic. To promote the insidious—“rape is hilarious”—is to join the crime at its own filthy level.

Those supporting Tosh are outraged that anyone would dare tell a comedian how to be funny. (There’s also been a lot of “if you can’t take the heat” sentiment aimed at this woman, given that she heckled Tosh.) Many of his defenders insist that his joke—and other jokes about rape—are simply edgy and controversial, which is what a comedian is supposed to be.

But here’s the thing: threatening women with rape, making light of rape, and suggesting that women who speak up be raped is not edgy or controversial. It’s the norm. This is what women deal with every day. Maintaining the status quo around violence against women isn’t exactly revolutionary.

That said, a comedy club is not some sacred space. It’s a guy with a microphone standing on a stage that’s only one foot above the ground. And the flip-side of that awesome microphone power you have—wow, you can seriously say whatever you want!—is that audiences get to react to your words however we want. The defensive refrains currently echoing around the internet are, “You just don’t get it—comedians need freedom. That’s how comedy gets made. If you don’t want to be offended, then stay out of comedy clubs.” (Search for “comedians,” “freedom,” “offended,” and “comedy clubs” on Twitter if you don’t believe me.) You’re exactly right. That is how comedy gets made. So CONSIDER THIS YOUR FUCKING FEEDBACK. Ninety percent of your rape material is not working, and you can tell it’s not working because your audience is telling you that they hate those jokes. This is the feedback you asked for.

And I know that when it comes to subjects as complex as rape, using exceptions can seem like slippery logic. That if we let one slip, then another, we might end up right back where we started. That “good” jokes and “bad” jokes seem too subjective, too flimsy a compass in which to measure.

But we also forget that anger is not the only response to social injustice. That we are also allowed to–and desperately need–a space of our own to talk back to it, make fun of it, not let it get to us.

I think the point of Lindy West’s article, in the end, is that when it comes to comedy, context is everything. With it, we have the most dangerous and clever kind of power. And without it, we have, well–Tosh.

Many online observers were quick to criticize Tosh’s comments but comedians were just as quick to back him up.

Alex Edelman, a professional stand-up comedian based in New York, told the Guardian: “I find rape to be a really serious topic, but on the other hand I think a comedian should be allowed to say almost whatever he wants and that the audience should be able to manifest their dislike in the form of not laughing at something if they find it offensive.”

A good comedian is an alchemist who can turn heckling into a transformative extended riff. Here it sounds like Tosh just doubled down on the same points he was making rather than actually responding, or providing an example of a rape joke that his heckler might find funny, undermining her objection. As I’ve written before, I think there is a case to be made that rape jokes that make fun of perpetrators can be very funny. Tosh didn’t go there, though. He just took the quickest route to run his heckler out of the club, and in using an image of her getting raped to mock and intimidate her, kind of made her point instead of his own. If rape was just hilarious and uproarious and trivial, it wouldn’t be a very effective rhetorical or literal weapon. Tosh isn’t just failing at civility here. He’s being a bad comedian.

We’ve had a lot of conversation on this blog about the way Daniel Tosh handled a woman who told him rape jokes weren’t funny at a recent show. There are a lot of threads to parse here—how people handle heckling (and how clubs should handle them)*, whether rape jokes can be funny under any circumstances, why comedians close ranks around their own. But I want to separate those issues out and talk very specifically about another strain of argument. One thread of conversation here has suggested that the woman who related her story was wrong, or oversensitive to feel threatened when Tosh suggested it would be funny if she were gang raped. The idea behind those objections is that no one would ever act based on Tosh’s words, and that because there isn’t a real prospect of her being actually assaulted, there is no impact to his words. This is wrong on two levels.

Comedian Daniel Tosh and the Culture of Rape in America by Beth via Veracity Stew

So, while comedians like Tosh shrug this off and say, It was just a joke, I will say, this isn’t a laughing matter anymore — not that it ever was — especially in a climate where women are being vilified and degraded for standing up for their most basic of rights, and to defend Daniel Tosh and his comments based solely on the fact that he’s a comedian, is unacceptable and inexcusable.

And here’s why:

These victims are mothers and daughters, sisters and wives, best friends and colleagues…in short, someone you may know and love. And you can rest assured that they probably will not see the “humor” in their plight.

When that woman stood up and said, “No, rape is not funny,” she did not consent to participating in a culture that encourages lax attitudes toward sexual violence and the concerns of women. Rape humor is what encourages a man to feel comfortable tweeting to Daniel Tosh, “the only ppl who are mad at you are the feminist bitches who never get laid and hope they get raped so they can get laid,” which is one of the idiotic, Pavlovian responses a certain kind of person has when women have the nerve to suggest that they don’t find sexual violence amusing. In that man’s universe, women who get properly laid are totally fine with rape humor. A satisfied vagina is a balm in Gilead.

These “little” things add up—maybe it’s a rape joke at the comedy club, plus a newspaper op-ed blaming the victim, plus a music video turning women into objects, plus a fellow student saying “that test raped me,” plus movies or TV shows that glamorize the “tough anti-hero taking what he wants without apology,” plus a family culture of silence and shame around sex, plus a police force who just goes through the motions when it comes to investigating or working to prevent sexual assault, plus a million other things—it’s a tsunami of shit. And you can add to it, or you can fight against it.

Imagine you’re in a country where people are still consistently assaulted for having dark skin. In this context you suggest that the lighter skinned people in the room whip a brown man into submission after he complains that jokes about darker people being persecuted aren’t funny. Might this make us uncomfortable? Probably, because when the brown man steps out into the real night outside the comedy club, there is a good chance he could actually get beaten and murdered. There’s also a history of this kind of violence actually happening around the world.

Does the “right” to joke about anything trump the realities of the place in which those jokes are being made?

Or imagine you are a heterosexual comedian in present-day Senegal (where being homosexual is illegal and gay men are often killed for being gay), speaking in front of an audience that includes people of various sexual preferences, and you make a joke about how killing gay people is always funny. And then a person in the audience shouts back “I’m gay and I don’t think it’s always funny.” And you proceed to say, hey, what if we beat up that gay guy right now? Wouldn’t that be hilarious?

As we would expect, his defensiveness is couched in “It’s just a joke” and the “I make fun of everyone” and “You’re too sensitive” rhetoric that is the stock in trade of hurtful comedians who want license to tell tired jokes that weren’t funny the first time they were told 100 years ago, but make people slightly uncomfortable so they must be saying something important. Comedians like Tosh compare themselves to guys like Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor, who said “offensive” things all the time. The difference, however, is that Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor were exposing the truth of our culture as wrong and in need of redirection, and comedians like Tosh merely reflect back the worst of us in a bald-faced and uncritical way. The way Tosh tells a racist joke venerates the racism, the way Pryor talked about racism made us aware that racism hurt people (while making us laugh). There’s an ocean of difference in that.

Daniel Tosh tried to make joke out of rape, and when someone protested, he shut her down with a threat of rape, which was not a joke but actual violence. When I, as well as other feminist bloggers, spoke up in support of this woman, we were threatened with rape to shut us down. It is ironic (and not in the cute hipster irony, but in the real deal kind), that the complaint many of Tosh’s supporters are making is that we are trampling on his creative process or freedom of expression by expecting him to be a decent human being. And they are using violent and cruel rape rhetoric to try to get us to shut up. We can’t use our freedom of speech to say, “What Daniel Tosh said crossed the line, and here’s why” but he, and his supporters, can use their freedom of speech to annihilate our humanity. IRONY!

What this confirms is that the whole Tosh thing isn’t about jokes. Tosh isn’t just a guy who tells stories on stage. He’s a guy whose comedy includes actually physically assaulting women, and directing his fans to do the same. And this is the guy who, after a woman challenged his rape jokes, mused aloud about how funny it would be if she “got raped by like, five” of those same fans, right then and there.

“Right now? Like right now? What if a bunch of guys just raped her?”

Damn.

Tosh uses some classic tricks to apologize, without really apologizing.

Trick One: I was misquoted. Tosh seeks to relieve himself of any responsibility, since, hey, he didn’t even say it.

Trick Two: I was the victim. Tosh seeks to undermins his apology by defending the point that started the entire interaction. He did nothing wrong but defend himself of a heinous violation–heckling! This is a weak apology at best and a passive aggressive dig at worst.

Does he really think people will not see the trickery he is employing to NOT apologize but say he is? Well, if he does, he’s right, because the media has reported his non-apology as the real thing.

Dear Comedians, and People Like Me Who Think They’re Comedians: Please Stop by Jonnie Marbles via Anarch*ish*

What made me stop telling rape jokes? I wish it had been what my sister told me, I wish I’d stopped that day instead of spending around a year loftily telling women why words couldn’t hurt them, that they should lighten up and that they didn’t get it. At first I felt I had to keep telling the jokes – had to! – simply because someone didn’t want me to. Otherwise I wasn’t being true to my art. It would be self-censorship. Comedians had to be free to say anything. Most importantly, how could I stay friends with the godawful, cowardly dickheads who told these jokes on a nightly basis if I turned around and said I wouldn’t? Sooner or later, though, I just couldn’t. Perhaps it was the jaw locking, knuckle clenching effect these jokes were having on the friends I brought along to shows. I’d sit next to them in the audience, see their discomfort, their disgust and realise I was doing the exact same thing up there, whether I knew it or not. Perhaps it was realising just how rarely rape is reported, and how making fun of it makes that less likely still.

What it’s like to be a woman living in rape culture. OR why I tweeted about the Tosh situation for 24 hours.

You can’t watch TV without being subjected to a rape joke. You can’t listen to the radio. You can’t browse Twitter trending topics. You can’t walk down the street without some jackass asking you, “Do I look like a rapist?” through his t-shirt. (And the answer is yes, yes you do.)

People use “rape” to describe how they were ripped off, or talk about “raping” the replay button on YouTube.

And you can’t discuss any of these cultural artifacts without people painting the purveyors of this brand of comedy in a golden, harmless light, while erasing the experiences of millions upon millions of sexual assault survivors—most of whom never report their assaults for fear of not being taken seriously. Hmm, now how can that be?

What Tosh and people supporting him don’t seem to get is that it’s not about freedom of speech or censorship or what’s funny and what’s not. Although I still contend rape jokes aren’t funny. But what’s really at the core of this situation is how we trivialize and disregard people’s pain, trauma and wounds. 1 in 4 women are raped. As I said before, Tosh crossed the line the moment he disregarded that woman’s concerns, asserted his male privilege and tried to humiliate her with a rape threat.

So why am I posting all these negative tweets? Is it just to call people out? Yes. But what’s more important is when we look at them as a collective. Then you begin to see just how prevalent and insidious rape culture truly is.

Tosh, you are currently at an amazing and terrible moment in your career. It’s terrible for (hopefully by now) obvious reasons. It could be amazing because at this moment, you have the opportunity to apologize (in a version that’s longer than 140 characters) and also to make an example of your situation and stop being offensive in your humor. You can show the world and comedians that there are more complex, interesting, and (ultimately) better ways to make someone laugh than by being offensive. And you can do it while people are watching and waiting to hear from you in the fallout of this event.

Molly Ivins once said “Satire is traditionally the weapon of the powerless against the powerful… when satire is aimed at the powerless, it is not only cruel — it’s vulgar.”

I stand behind that 100%. Humor in the hands of a bully is just much less appealing than humor used to point out how ridiculous the bully is being. It may technically still be humor, and it may still be the Constitutional right of that bully to make those jokes, but thinking that a bully’s jokes aren’t funny doesn’t make me a stick in the mud, it makes me a decent person.

Rape culture is when self-appointed guardians of “traditional values” like Rick Santorum tell rape victims that, yes, rape is horrible, but if your rapist impregnates you, it’s “nevertheless a gift in a very broken way, the gift of human life, and accept what God has given to you.” Aw, rape victims no doubt think to themselves, an unwanted pregnancy conceived in rape? For me? From God? Awesome! After all, despite the ugliness of rape, says Rick, “We have to make the best out of a bad situation.” As even the most causal readers of this series know, according to Mr. High and Mighty, making the best out of bad situation means passing laws to force women who’ve been raped to carry their rape-babies to term. And a “Gee, thanks, God!” wouldn’t hurt, you ungrateful, selfish bitches. Just because you’ve been raped is no excuse to be thinking about yourself. There are more important considerations than the trauma of your violent assault—like how male politicians feel about your violent assault and how they feel that you should feel about it. That’s rape culture.

Not everyone’s going to agree, and some people are going to think I’m a bad feminist, which, what else is new. But I want to be able to link to this post in the future, when this happens again–because it always does–and hordes of young men start screaming–because they always do–that feminists are trying to take all the funny out of comedy AGAIN.

I am a feminist. I have been raped. And I think the following 15 rape jokes are hilarious. So please fuck all the way the fuck off with your “You just don’t understand comedy” bullshit. (Here’s an alternative proposal: Maybe you just don’t understand being a decent human being.)

Here’s what YOU need to understand:

1) Rape is way, WAY more prevalent than you seem to think it is. Are there more than five women in your audience? You do the math, and then you run the little fantasy scenario that I just put together in your head, and you tell me how it feels.

2) I ain’t buying any of that “If I can make jokes about genocide, why can’t I make jokes about rape?” Horseshit, unless you made those genocide jokes during a gig at the Srebrenica Funny Bone. You got away with making a joke about genocide because your odds of having a holocaust survivor’s kid in the audience were pretty fucking low.

And if you did happen to have one in the audience, and he heckled you, walked out, and wrote something nasty on the internet… would you be more likely to be a human being and say “Wow. I can understand why that person’s authentic response to what I was doing was so emotional and negative. Maybe my genocide material just isn’t good enough to justify the pain that it inflicts. Maybe I need more skill in order to pull this off.” Or are you gonna be a lousy piece of shit and say, “Yeah, I apologize, I guess, IF YOU WERE OFFENDED.”

Offended hasn’t got anything to do with it, moron.

I’m not a comedian, and am only occasionally (mostly not on purpose) funny. I’m not here to comment on humor or what passes as a joke these days. However, an unintended conversation on Twitter yesterday, coupled with a story from a friend got me thinking.

Last night I found myself engaged with a comedian who didn’t quite understand why everyone was so up in arms over Tosh’s “joke.” Relax. Take a chill pill. You’re overreacting. You have no sense of humor, etc… I did my best to not engage, but when he verbally attacked a friend of mine, I stepped in. I was rational. I was calm. I made some logical points. And yet…

(I’ve chosen not to share screen caps of our conversation because I don’t need to give this guy any more attention. The bolding/color highlighting are my doing).

The answer to this bogus claim, of course, is that humor is at its best when it subverts the norm. In a rape culture such as ours, the norm is to pile scorn and disbelief upon victims and excuse perpetrators. So rape jokes that further humiliate victims aren’t edgy, they’re just bullying. But jokes that call attention to rape culture can be funny and even receive the feminist seal of approval.

A number of awesome feminist friends of AlterNet from the Women’s Media Center, PopCulturePirate, Women In Media & News, and Fem2pt0 teamed up this week to create a “supercut” of a variety of rape jokes, including several from Daniel Tosh which in my mind show exactly on which side of the line his particularsense of humor lies. The video, however, makes no overt judgments, but asks audience members to decide for themselves where that line is, what makes them laugh, and what makes them uncomfortable.

It seems that the heart of this incident is the question of whether or not it is appropriate for comedians to joke about rape. It could be argued that in this case, people defending Tosh are arguing it is appropriate to threaten someone with rape in a comedy club (since, if we use their logic, supposedly in the context of a comedy club, this is not meant to be taken seriously since it is just “a joke” that you might not “get”).

But the real heart of this, and the reason it has struck a chord with so many people, is that it is a simple sad illustration of rape culture at work.

Daniel has made jokes about black men, Latino men, and other non-white men raping women because they’re all animals who can’t control their dicks.

When his rape jokes were rooted in racism, no one gave a fuck.

I wonder if this spurt of rape jokes/threats/insults is not as out of the blue as we would all like to think. I see it as starting with prison-rape jokes. No one seemed to bat an eyelash when we used jokes like “don’t drop the soap” or “you’ll end up with a cellmate named Bubba” or even “they have a way of taking care of people who fight dogs/pedophiles/wife-abusers in jail.”

Then along came movies and television shows in which male rape was funny. I was appalled by a scene in Get Him To The Greek in which a male star is anally raped by a woman wielding a large dildo. Then came True Blood in which Jason Stackhouse was gang raped by women. His trauma was minimized and the rape(s) were written as a humorous comeuppance for a serial womanizer.

First, let’s get a few quick things out of the way: (1) This is totally in keeping with Daniel Tosh’s humor and style. He’s a lousy Reddit thread come to life, which is why he is so popular! (Just ask Jeff Dunham.) (2) Don’t heckle comedians, no matter how offensive and crappy you think their material is. (3) There’s no such thing as off-limits in comedy, and comedians are always — always — entitled to make jokes about whatever they want. But “entitled to” and “obligated to” are not the same thing, and comedy is not immune to criticism.

That’s 30 rape jokes in one segment. One segment in a half-hour show on Comedy Central. That averages one rape joke per minute. I’d love to know the demographics of his viewing audience, but I don’t even have to look to feel confident they skew heavily in the 18-34 range. Which is terrifying to me.

Sure, one can find humor in anything, but I’d like to think that humor is most often found by those who have experienced something. Humor in healing, humor in dealing. Not aggressive, unnecessary and belittling humor that essentially robs the victims (in general as well as those specified) of the fact that they. were. victimized.

Nonetheless, the significant overlap between the gender divide and the rape-joke empathy gap is real, and it seems inevitable when media coverage of rape so often focuses on what a victim should have done differently to try harder not to get raped. Such shoddy framing creates a fictional image that there’s a certain type of woman who gets raped. Women know that’s a lie, because they live the truth, but men may never have occasion to question that image, and so when they laugh at rape jokes, they’re laughing at an abstraction that’s all too real for many women.

Tosh and all those with the privilege to hold a microphone have a responsibility to shine a light on the reality behind the abstraction — not to perpetuate it, and certainly not to silence those who bear its burden.

UPDATE: I also want to quickly address the argument I’m seeing a lot that Louis CK should be given “credit,” or some variation thereof, for either “evolving” on rape culture and/or speaking about rape culture on a national platform, despite the rest of his objectionable shtick.

First of all, contemplating rape culture for the first time as a 44-year-old man with two daughters, and patting oneself on the back for it instead of framing it as the profoundly regrettable evidence of privilege that is is, isn’t something that ought to be praised—and praising it breathes life into the terrible idea that rape culture is difficult for “men” to understand. That is not accurate. It’s not difficult for lots of male survivors; it’s not difficult for lots of trans* men; it’s not difficult for lots of gay men; it’s not difficult for lots of men who have been incarcerated; it’s not difficult for lots of men who are vulnerable by virtue of physical disability; it’s not difficult for lots of highly privileged men who simply have the willingness to listen to women.

Let us not confuse “difficult to understand” for “easy to ignore by virtue of privilege.”