This guest post written by Charlotte Orzel appears as part of our theme week on Ladies of the 80s. | Spoilers ahead.

In the fall of 2014, an early example of “peak nostalgia” saw a television adaptation of Cameron Crowe’s 1989 rom-com Say Anything announced and then canceled within twenty-four hours at NBC. According to Deadline, the series would have continued where the film left off:

“Set in present day, the Say Anything series picks up ten years later. Lloyd has long since been dumped by Diane and life hasn’t exactly turned out like he thought. But when Diane surprisingly returns home, Lloyd is inspired to ‘dare to be great’ once again, get Diane back and reboot his life.”

This pitch gets straight to the core of the troublesome way Say Anything has been remembered. People think of the film as synonymous with its iconic image of Lloyd Dobler (John Cusack) holding a boombox over his head with his heart on his sleeve. Audiences remember Lloyd as the rare romantic lead who approaches the girl he loves with respect, earnestness, and unshakable optimism. They appreciate the way love let Lloyd “dare to be great.”

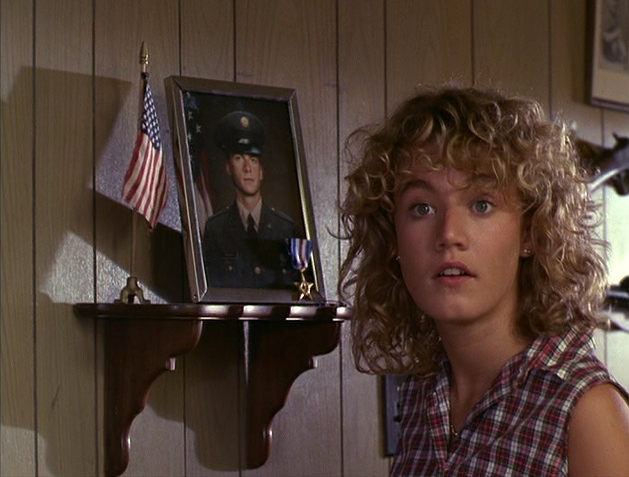

The problem isn’t that audiences misremember Lloyd Dobler; it’s that they forget about Diane Court.

Even though the two characters share the screen more or less equally, Diane (Ione Skye) is often treated more as a love interest than a romantic lead. Take this example from Total Film’s 50 Best Romantic Comedies:

“The sweet Lloyd Dobler (John Cusack) might be an average student, but he aims high when he asks valedictorian Diane Court (Ione Skye) out on a date. Her affluent lifestyle and his humble upbringing make the two a perfect ‘opposites attract’ pair as he helps her overcome her shyness and the ability to drive a stick shift, and she… well, loves him.”

From this summary, and others like it that have been published since the film’s release, you get the picture of a romance that sees Lloyd Dobler as a sweet, earnest slacker, rise to his potential to win the heart of a beautiful, sheltered girl. He teaches her how to live, and she is eventually won by his charm, wit, and ability to raise a boombox over his head for the entire length of “In Your Eyes” (an admittedly impressive five and a half minutes).

What really happens is quite different. Not only is Diane an equal player in the action; she’s the film’s protagonist. While we spend a great deal of time with Lloyd, the movie’s story is structured around Diane’s life. In the summer after graduation, she has much more on her plate than Lloyd, who when asked about what his summer job is, replies, “I want to see you as much as possible before you leave.” Lloyd’s future is uncertain, but he’s not too worried about it, as long as it includes Diane. Diane, on the other hand, is incredibly anxious about what lies ahead — she has been offered a prestigious fellowship to England and her father is being investigated by the IRS — and her growing feelings for Lloyd complicate things considerably. We watch her navigate her fears for the future and reconcile them with Lloyd’s idealism which, despite her crushing sense of responsibility, she finds incredibly appealing. These issues are not merely set dressing for the romance, like many romantic comedies that give their heroines a wisp of a life to differentiate them from one another, like a set of Career Barbies. Her father’s investigation forms a solid B-plot that is frequently left out of retellings.

In the first few minutes we spend with Diane, she gives a valedictory speech which communicates not only the tremendous expectations on her shoulders, but her own ambivalence about life after high school. It becomes immediately apparent that Diane’s fears run far deeper than a kiss from Lloyd can soothe. In a later scene with her father, when she learns that she’s won a competitive fellowship in England, her initial response is to sink to the ground, worrying: “I’ll have to go on a plane” (we later learn that she has been afraid of flying since she was young). Diane is not only brilliant, shy, and beautiful, but desperately afraid of what the future holds.

Meeting Lloyd opens Diane up to the possibilities of life outside the rigor of constant achievement. Their first date is not a swoony, candlelit affair or a twee romp, but a bustling graduation party where they spend little time together, but keep track of each other over the heads of their classmates. Diane, initially asking if it would be “terrible if [she] wanted to go home early,” enjoys herself and talks eagerly, if awkwardly, with the other students, eventually calling her father to tell him that she’ll be home before dawn.

In the car on the way back from the party, the two finally connect in a conversation about how their classmates perceive them. Unlike her father, who constantly and almost unconsciously affirms her, Lloyd listens with a kind ear to Diane’s insecurities and doubts. Lloyd represents more than the potential for romance, which Diane has in the droves of suitors (and their droves of cars) her father fields on the phone. He offers her a chance to be afraid, imperfect, and vulnerable, to reach out and connect genuinely with other people, and, most importantly, to be known in turn.

Rather than holding Lloyd at a distance, Diane brings him into her world, introducing him to her father and showing him around the nursing home where she works. He teaches her to drive stick shift, gently letting her be bad at something for what might be the first time in her life. They share their first kiss. Inseparable after that, they soon have sex, which Diane awkwardly has to explain to her worried father when she doesn’t come home that night. Tentative but sure, she pushes at the boundaries of her old life, neglecting to call her father and unable to reason her way out of her attraction to Lloyd.

Then, with her fellowship in England looming on the horizon and the IRS investigation growing ugly, Diane breaks it off suddenly when Lloyd tells her he loves her. She shares her feelings, but begs him not to “put things on this level.” The seriousness of their relationship seems to only deepen her worries about the murky future. Both parties despair, Lloyd leaving Diane a string of voicemails that she screens anxiously, clearly longing for him. Though she is touched by his attempts to change her mind, including the iconic boombox scene, these gestures are not what eventually move her to return to him. Far from the popular idea of Lloyd as the persistent, charming guy who wins the girl through earnest passion, he doesn’t win her back at all. Instead, she turns to him when she discovers her father is guilty of tax fraud. This revelation not only shatters any hope of her returning to her sheltered life, but reminds her of the value of her relationship with Lloyd, who is as open and honest with her as she is with him.

Confronting her father, she is devastated that he lied to her and shrinks from the idea that he wants to use his illegal gains to “set [her] up so [she] doesn’t have to depend on anybody.” When she goes back to Lloyd, she tells him that she needs him. Lloyd asks, “Are you here because you need someone, or because you need me?” following it up by telling her, “Forget it. I don’t care.” But Diane does. The girl who kept everyone at arm’s length has finally found someone she truly knows and can rely on.

The final scene of the film seals this realization, as Diane embraces the uncertainty of her future in England with Lloyd by taking on her major fear: flying. Diane confronts the doubts surrounding her relationship with Lloyd and her fear of flying by accepting the potential for failure. Like Diane, the ding of the smoking light that signals the most dangerous part of the flight is over reassures us, but doesn’t eliminate our worries about the couple’s fate. We don’t know what their future holds, only that the scariest part is over. The plane could still crash. It’s just more likely that it won’t, and that’s enough.

While Diane has a clear narrative of growth, Lloyd is a static character. The film opens on him declaring his intention to win Diane’s heart, and closes on him having achieved his goal, but he remains earnest, steadfast, and optimistic throughout. Diane’s choices, not his, push the story forward. The movie flirts with remedying his lack of career ambition, having first his guidance counselor and then Diane’s father scorn his refusal to commit to a plan for the future. However, he ultimately concludes that his relationship with Diane is enough to sustain him. The movie cheekily points out his lack of development in a scene when he visits her father in prison, and tells him that he probably should start working on his own goals, but has decided to go to England with Diane instead.

This lack of ambition is what has led some to argue that Lloyd and Diane never would have made it work in the long run. In what may be the most cynical article of all time, Dustin Rowles speculates about how things turned out for the characters, concluding that Lloyd’s slacker attitude would wear on Diane and sooner rather than later, she would have cut him loose to go after a graduate student. The NBC pitch also suggests that a breakup between the two was inevitable. But assuming that Lloyd and Diane would split reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of what brought them together in the first place. Lloyd doesn’t win Diane with his wit and laid-back attitude; his honesty and warmth encourage her to open up and make herself vulnerable enough to forge a real connection. Eventually, she chooses him because his unflagging optimism balances out her stymieing fear of the unknown. If we imagine that Lloyd won Diane over with his persistence, it’s easy to imagine her becoming disillusioned later on. If we remember that she chose him, and in doing so, took a step forward in becoming the kind of person she wanted to be, writing off their relationship as misguided becomes much harder.

In light of Diane’s place at the center of the story, why is Lloyd given so much more prominence when we talk about Say Anything?

In the years before and since the movie’s release, John Cusack’s star has burned brighter than Ione Skye’s. Since the two actors have almost an equal amount of screentime, that may make it slightly easier to imagine Cusack as the lead. While one could conceivably argue that Lloyd is a more unique and fully realized (or better acted) character, a close look at Diane suggests that conclusion is unfair. Not only is Diane’s shy, anxious braniac just as uncommon a sight onscreen as Lloyd’s witty, earnest slacker, but Crowe and Skye fill her in with loving detail. Diane is just as complex and interesting a character as Lloyd. However, for the audience of teen romance, imagined by marketing executives as young, female, and heterosexual, the male character is often made the object of desire and attention in both marketing and the film itself. This is particularly true in a genre that often makes its female characters bland and one-dimensional on the assumption that it will allow female viewers to more easily insert themselves into the story. And naturally, when male protagonists are more common and valued more highly than female ones, many viewers are already in the habit of bending over backwards to sympathize with the male perspective. These ways of watching are so ingrained that we may end up imposing them ourselves, even when films like Say Anything offer us a more nuanced alternative.

The NBC series pitch leans on these viewing habits by setting Lloyd up as the main character of the show. He is the one whose “life hasn’t turned out like he thought,” who must “reboot” to regain his old energy and idealism. But the movie worked in the first place by watching Diane grow out of her fear of the future. By undermining the ambiguity of the original ending, the TV pitch ignores the way that accepting both the hope of success and the possibility of failure was an essential resolution for Diane’s character arc. The pitch assumes that Diane was a catalyst for change in Lloyd once before and will be again, even though the movie works precisely the other way around. Say Anything didn’t dare Lloyd to be great. It dared Diane to embrace her greatness, and let us watch as she rose to the challenge.

Charlotte Orzel spent a few formative years scooping popcorn at an independent movie theatre, and in the process fell in love with film, television, and criticism of all kinds. She is a Master’s student in Media Studies at Concordia University in Montreal where she studies new initiatives in film exhibition. She tweets about her interests and adventures in writing and academia at @charlotteorzel.