|

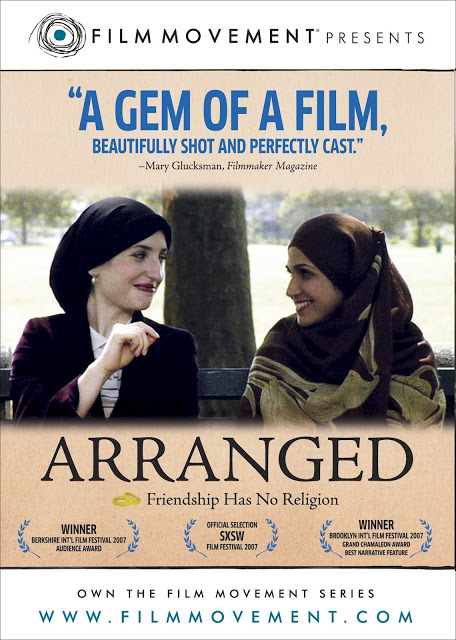

| Saber Sharifi trains women boxers in The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

This is a guest post by Rachael Johnson.

The Boxing Girls of Kabul is a Canadian documentary about the boxing careers of three young Afghan women, sisters Sadaf and Shabnam Rahimi and Shahla Sikandary. It was written and directed by the Afghan-Canadian filmmaker Ariel J. Nasr. Based in Afghanistan, Nasr produced the recently Oscar-nominated live action short, Buzkashi Boys (2012).

The Boxing Girls of Kabul opens with harrowing archival footage of an execution of a woman at the Olympic Stadium in Kabul on November 16th, 1999. Many will recall this secretly-recorded film from news reports, but it will always disturb and haunt: the kneeling woman, clad in a pale blue burqa, attempts to turn her head to her executioner as she is about to be shot. Mercifully, the camera cuts to a blue sky and carries us directly to contemporary Afghanistan. We see, in close up, the determined brown eyes of a young female boxer training at the very same stadium where women were executed during the dark days of Taliban rule.

We are first introduced to Sadaf who tells us that she and her fellow fighters spar in the same gym where girls were imprisoned. She is somewhat frightened by the place itself but explains, “When we play sports, we forget our problems. When I box, I feel happy. I box because I want to advance myself, and advance Afghanistan.” Sincere and ambitious, the girls want to determine their own destinies. Shahla says, “In the future, I want to be the most progressive and bright of all Afghan girls…a champion.” All are hungry for medals.

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

Boxing has always, of course, been the most traditionally masculine, most brutal and most controversial of sports. Female boxing remains a divisive issue around the world and only became an Olympic event at the London 2012 Games. It is all the more remarkable that girls from a land scarred by gender discrimination have taken up the sport. The girls’ coach, Sabir Sharifi, explains, “The Taliban were absolutely opposed to sports. They had an especially strong opposition to boxing.” A girl boxer in a hijab is an incongruous image for many–or most–Westerners. For the Taliban, female boxing is simply sinful. Boxing has also, however, been the sport of the marginalized and oppressed so it is perhaps unsurprising that these young Afghan women have chosen boxing. The sport for the trio is identified with self-empowerment and female self-worth.

It is interesting to see the boxing girls of Kabul negotiate the streets and shops of the capital with their trainers–as well as journey abroad for competitions–but the interviews with them and their families at home and in the gym provide a more intimate and perhaps more illuminating portrait of the nature of their lives. In the locker room, we see the trio and their peers talk about exam results, tease each other about their hair and spray bottled water over each other. These glimpses serve to remind the viewer that their interests and aspirations are fundamentally the same as most young women around the world. They also give a strong idea of both their incomparable pressures and camaraderie.

Nasr also provides helpful insights into the attitudes of the men in the boxers’ lives. Their coach is a very likeable, middle-aged man. Sharifi formed the girls’ boxing team in 2007 with “a few brothers.” He himself was a victim of Afghan’s tragic, war-torn history. The 1980s Soviet occupation, he explains, put an end to his Olympic ambitions. Sharifi and his colleagues consistently demonstrate support and affection for their charges. He says he wants champions. There persists in the West an Islamophobic, racist belief–even among self-proclaimed progressive people–that all Muslim men in all Muslim lands dominate, control and persecute their daughters. The forward-thinking likes of men such as Sharifi constitute a formidable response to such bigotry. He is not alone. Shahla explains that it is her father who supports her the most in her family. “He thinks that a girl can be someone in the future,” she says. Sadaf and Shabnam Rahimi’s father is also encouraging while their progressive mother wants them to continue both their education and sporting career.

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

Female boxing, of course, enrages the Taliban and Afghan conservatives in general. The girls are given the opportunity to compete in Vietnam and Kazakhstan. Unhappily, increased recognition brings increased intimidation for both trainer and coach. Sharifi is threatened on the street while Shahla experiences pressure to stop boxing from her brother. He is shown to be infinitely more conservative than her father. In English, he expresses concern that his sister’s boxing career will endanger the family in the event of a full-blown Taliban resurgence. He worries that the family will be accused of being “kuffar” (non-Muslim). “Nothing except this,” he insists. But is he merely motivated by concern for his family’s safety? He scorns his sister’s independence, accuses her of not praying with satisfactory piety and delivers this extraordinarily unsettling threat: “If I was in my father’s place, I would set so many restrictions she wouldn’t even be able to eat without being afraid.” But the girls bravely pursue their sport despite these difficult and dangerous circumstances.

There are other obstacles. Funds and facilities are inadequate. They do not even have a ring. In Vietnam and Kazakhstan, we see them outclassed and overwhelmed by their hosts. It is painful to watch, but I was reminded by a quote by the novelist and boxing writer Joyce Carol Oates: “Boxing is about being hit rather more than it is about hitting, just as it is about feeling pain, if not devastating psychological paralysis, more than it is about winning.” The girls, understandably, complain of inadequate training and resources, but they are also, of course, cutting their teeth. Shahla is fortunate to secure a bronze medal in Vietnam–there were only four in her weight class–gaining the attention of the Afghan media. Her father is proud of her achievement.

We learn, at the end of the documentary, however, that Shahla no longer competes. Pregnant with her first child, she visits the gym “when she can” and works part-time. You wonder if she will return. It is heartening though to hear that Sadaf continues to compete and that Shabnam aims to be a doctor. Perhaps they have been empowered by their mother’s words: “In Afghanistan, we have to fight against men to show we have pride.”

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

Documentaries like The Boxing Girls of Kabul are invaluable in that they give voice to the voiceless. These young women possess a rare courage. Spirited, ambitious and attractive, they make engaging subjects. The cinematography (by Nasr) is not particularly striking in The Boxing Girls of Kabul and it is a no-frills documentary formally. The director is modest and unadorned in both style and approach. The interviewer is a silent presence; the boxers as well as trainers and family members speak for themselves. This works well as they appear to reveal their hopes and fears quite openly. The documentary, however, is simply too short at 52 minutes. The trio’s stories could have been further developed. It is evident that they box for themselves, their gender and their country, but it would be have been rewarding if the filmmakers had explored their motivation more deeply. Their influences could also have been cited. Which fighters (male or female) inspired them?

The young women are trail-blazers in a patriarchal society still plagued by religious extremism. They are, equally, children of war. For decades, Afghanistan has been blighted by conflict. Bizarrely, the documentary does not mention that ongoing war between foreigners and the Taliban. The prolonged presence of the American military in Afghanistan is curiously absent from all conversation. It would have been interesting to know the boxers’ thoughts on the conflict as well as the role of the West in relation to the status of women in Afghanistan. The Boxing Girls of Kabul gives relatively little historical background and context. It does not explain how the Taliban came to power or shed new light on their mindset. (If you want to learn about the roots of Taliban, start with Ahmed Rashid’s 2000 book Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia.)

Listening to Shahla’s conservative brother was, then again, quite enlightening. His obsession with what others think reveals a deep lack of imagination and reflects a fear of difference. Social conformity seems to have a tyrannical hold on him. The documentary does, however, unsettle stereotypes about both Afghan men and women. This is invaluable. Nasr has created an affecting, compassionate portrait of proud, independent Afghan womanhood in The Boxing Girls of Kabul. Ultimately, there are few things more moving than witnessing the endeavors of an oppressed group or people.