Written by Andé Morgan.

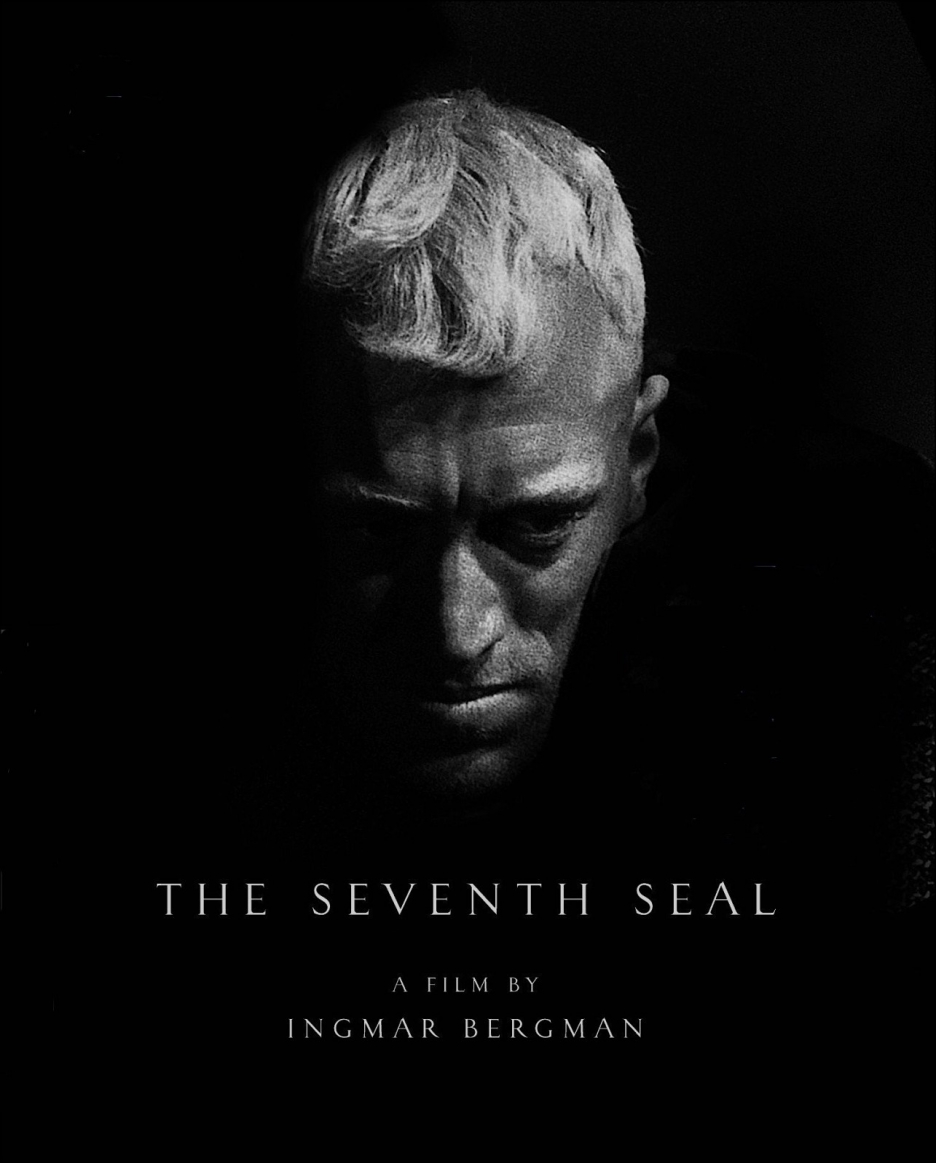

The Seventh Seal was released in Sweden in 1957. The title is a reference to the Book of Revelation (Rev. 8:1): “And when the Lamb had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour.” Ingmar Bergman’s 17th film examines the big question: where is God? Set in Sweden in the 14th century during the Black Plague, the film documents the travels of the knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) and his squire, Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand), as they return home from the Crusades (this is one of many useful anachronisms in the film, just go with it). Block is literally pursued by Death (Bengt Ekerot). Along the way, Bergman also muses on love, isolation, and death.

This film is a classic. If you think you haven’t seen it, you are wrong. You have seen it by way of parody in The Colbert Report, Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey, Last Action Hero, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, and others. Bergman’s mastery of dialogue and symbolism is on constant display in the film. While not typically considered Bergman’s best work, it was a critical success and solidified his position as a leading director and screenwriter of the post-war era.

War-weary Block and his fatalistic squire Jöns return home after fighting in the Crusades to find Sweden in the grips of the plague. The film’s most iconic scene comes early: after gaining the beach, Block sees Death anthropomorphized as a white-faced, severe-looking man in monk’s garb. Death’s intent is obvious, so Block challenges him to a chess match on the condition that the knight may stay alive during the match, and permanently should he win. Death readily accepts the challenge. Neither Jöns nor the other characters see Death; they assume that Block is playing chess alone.

On the way to Block’s castle they meet some actors: Jof (Nils Poppe) and his wife Mia (Bibi Andersson); their baby Mikael; and the head of their troupe, Skat (Erik Strandmark). Like Block, Jof has second sight, but the others think him a fool.

Block and Jöns enter a church where a rough-hewn painter is installing a fresco depicting the Dance of Death. Block goes to the confessional where he talks about his conversation with Death and admits to the priest that he feels his life has been futile and meaningless. He also discusses his chess strategy, prompting the priest to show his face and reveal that he is Death. Understandably perturbed, Block leaves the church. On the way out he notes a young woman, Tyan (Maud Hansson), bound to the church wall. She is called a “witch” and has been condemned to death for consorting with the devil and bringing the plague upon the village as God’s punishment.

Meanwhile, Jöns searches for water in the plague-ridden village. In an abandoned barn he spies Raval (Bertil Anderberg), a religious type who ten years earlier convinced a presumably more faith-filled Block and Jöns to join the crusades. Raval is robbing the corpse of an older woman. A girl (Gunnel Lindblom) stands stunned in the corner. Ravel notices the Girl, and attempts to rape her. Jöns stops Raval, and the Girl joins their group.

Block, Jöns, and the Girl enter a village where Skat and his troupe are performing. Plog the blacksmith’s wife, Lisa (Inga Gill), surreptitiously runs off with Skat. The performance is then interrupted by a procession of flagellants. Later, following another encounter with Raval at the local pub, some dancing, and a pleasant picnic, Block invites the Girl and Jof’s family to join him at his large, fortified home. On their way through the forest to the castle, they find Skat and Plog’s wife. Lisa, tired of Skat and frightened of Plog, goes back to her husband.

The group is then intercepted by the execution party, dragging a cart holding the bound woman from the church. Block asks her to summon Satan so that he might query the evil one about the nature of God. While Tyan complies, Block is unable see the Devil. Instead, he notes only her terror, and gives her water and herbs to ease her pain.

After Tyan’s execution, Raval reappears, now afflicted with the plague and begging for water and comfort.. Of the group, only the Girl shows pity for the attempted rapist. She moves to bring him water, but Jöns stops her. Meanwhile, Jof’s second sight allows him to see Block resume his chess game with death. Jof moves Mia and Mikael aways from the group while Death is distracted. This escape is aided by Block, who occupies Death momentarily by turning over the board with an errant arm. After returning the pieces to their proper places, Death mates Block. When they meet again, Block and his company will follow Death to the grave.

Block, Jöns, Lisa, and Plog, make it to the castle. All the servants have left, leaving only Block’s wife, Karin (Inga Landgre). As the group eats a solemn last meant, three knocks on the door precede the appearance of Death. Block implores God, “Have mercy on us, because we are small and frightened and ignorant.”

Having escaped the clutches of Death (at least temporarily), Jof and family sit out a large storm that Jof likens to the “Angel of Death.” After the storm, Jof sees Block and his company being led by Death in a creepy danse macabre. The film closes on the travelers, dancing and holding hands under a dark cloud.

It is standard practice for critics to either praise The Seventh Seal for it’s stark symbolic grandeur or to pan its lack of subtlety. While still thought of highly, in our time the film’s status has diminished. Flush with symbolism and weaned on metaphor, we often take directness for weakness, and earnestness for naiveté. However, as many others have noted, the strength of the film is its unabashed allegory. In this way, the portrayals of the female characters, along with Block and Jöns’ dialogue, convey Bergman’s feelings about women. I argue that Bergman’s views parallel the gross biblical dichotomy which views women as either holy vessels or promiscuous deceivers.

Most obvious is Mia; she, Jof, and Mikael represent the Holy Family. Mia is pure, and a comfort to Jof and Block. In the picnic scene she bestows to Block a simple meal, a bowl of strawberries and milk, as if passing him the Eucharist.

“…Also, I infused the characters of Jof and Mia [some might say Joseph and Mary] with something that was very important to me: the concept of the holiness of the human being. If you peel off the layers of various theologies, the holy always remains.”

– Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Films

While Block is content to be comforted, Jöns’s attitude towards women represents more of an Old Testament approach. In the Church, Jöns remembers “leering at girls” and catching lice from women in the Holy Land. Upon preventing the Girl from being raped by Raval, Jons forcefully embraces her. Deflated by her quiet resistance, he relents, saying that he is “tired of that kind of love,” (i.e., tired of rape). Later, while discussing Lisa’s infidelity with Plog, he says that, “Yes, it’s hell with women and hell without them. So, however you look at it, it’s still best to kill them off while it’s most amusing.” It is difficult to discern if this remark stems from Jöns’s true feelings, or from his nihilistic cynicism.

When Jöns and Plog catch up to Lisa and Skat, Lisa incites Plog to murder Skat. While Skat outwits Plog, Death ultimately conveys the blame for the adultery by felling the tree the actor has taken shelter in, killing Skat and enticing a cute squirrel to clamber atop the new stump. In all, Lisa’s seduction and deception of Skat and Plog seem to loosely parallel the Old Testament stories of Delilah and Jezebel.

The suffering of Tyan, the witch, is disturbing. We see a young woman, restrained and with broken hands, sentenced to an agonizing death. While the men who chained her claim that she has had sex with Satan, and thus has brought God’s wrath upon the entire village in the form of the plague, we the viewer can plainly see that Tyan is a scapegoat, and probably only guilty of more conventional human sexuality. Block, who seemed sympathetic during their first meeting, reveals in their second meeting that his primary interest in her is in the veracity of her charge. He hopes that she really is in league with Satan because if she can know Satan, so can he, and by extension, so can he know God. While Tyan’s role in the story ultimately is to support Jöns’s argument against the existence of God, the viewer cannot help but recall similar contemporary atrocities, e.g., women being murdered around the world in the name of religion or for their real or perceived sexual activity.

The Seventh Seal is not a feminist film. The story’s protagonists are male. Tyan, the film’s most compelling female character, dies a horrible death in the service of Jöns’s argument. Women are portrayed as religious tropes: Holy Mother figures, witches, or Jezebels. While annoying, this simplicity is in keeping with the earnest symbolism that Bergman aimed for. In hindsight, how lovely it would have been if Bergman had written a strong female character to join Block and Jöns in contemplating not only the silence of God, but also the intersection of religion and misogyny. Still, watch the film for the cinematography, the dialogue, and to be reminded that sometimes subtlety is overrated.

Andé Morgan lives in Tucson, Arizona, where they write about culture, race, politics, and LGBTQ issues. Follow them @andemorgan.