Do not draw back, for we will mourn with thee

O, could our mourning ease thy misery! (2.4.56-57)

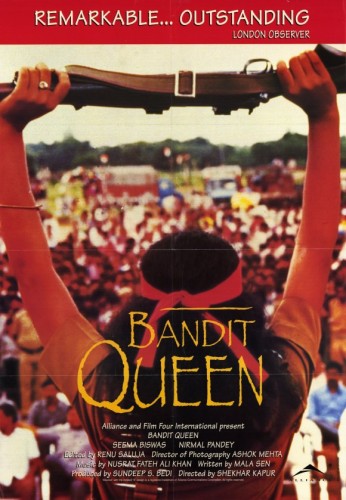

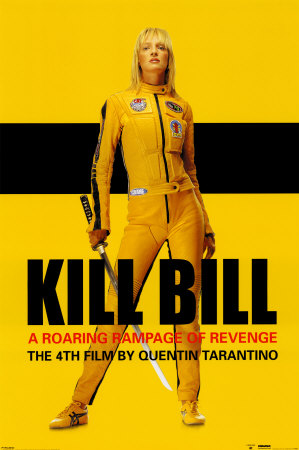

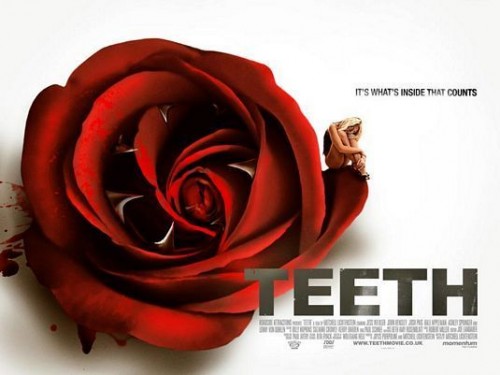

This repost by Leigh Kolb appears as part of our theme week on Rape Revenge Fantasies.

When a story about a girl who was raped and subsequently shunned and blamed breaks, I’m no longer surprised. It’s familiar. Townspeople gathering behind the rapists–just like in Steubenville–seems like the natural course of things in our toxic rape culture. She shouldn’t have been so drunk. She couldn’t say no. These boys are promising young athletes.

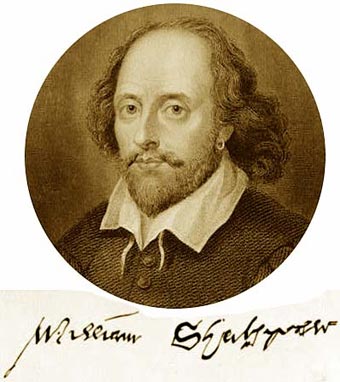

When Shakespeare wrote Titus Andronicus and The Rape of Lucrece in the late 1500s, women were quite literally the property of men (their fathers, then their husbands). The rape culture that plagues us in 2014 was essentially the same, although laws of coverture have dissolved and women are no longer legally property.

And Shakespeare understood the horror of rape. Shakespeare–more than 400 years ago–seemed to understand that patriarchy hurts women. Patriarchy kills women.

Patriarchy is rape culture.

I read about the Maryville case with the familiar dread that accompanies these too-frequent stories. When it happens in my state in a town that looks like mine, it’s even closer. But I’m never surprised.

As I was watching Titus with my Shakespeare class just a few days later, I readied myself for the rape scene (which Julie Taymor handles brilliantly). When Lavinia’s uncle, Marcus, finds her brutalized, he delivers a long monologue, mourning the sexual violence that she has gone through.

At the end of the monologue, he says as she turns away,

“Do not draw back, for we will mourn with thee

O, could our mourning ease thy misery!” (2.4.56-57)

It took my breath away like it hadn’t before, and I checked the text to read the exact quote. I paused the film and asked my students if they’d heard of the Maryville case (in which the victim and her family were basically chased out of town after the case against the perpetrators was dropped). They hadn’t. I explained, and re-read out loud the final couplet of Marcus’s monologue.

Is this how we respond to women who are raped in our culture?

What if we did? What if we rallied behind not the rapists, but the one who was raped? What if we never said, “I am not saying she deserved to be raped, but…“

What if all of this happened immediately and swiftly in our own communities, and not after a case gets national attention?

In Shakespeare’s texts, it’s clear that the rapists are sub-human and villainous. Even when rape isn’t part of the plot, he shows the figurative and literal violence of patriarchy.

Hermia’s father is willing to kill her if she doesn’t marry who he wants her to marry in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. (“I would my father look’d but with my eyes,” she says.)

Hamlet‘s Ophelia commits suicide when she descends into madness from being pushed and pulled by patriarchal pressures. (She says to her brother after he advises her to be chaste and virtuous, “Do not, as some ungracious pastors do, / Show me the steep and thorny way to heaven; / Whiles, like a puff’d and reckless libertine, / Himself the primrose path of dalliance treads, / And recks not his own rede.”)

Emilia’s views on the patriarchal constraints of marriage and sexuality in Othello seem radical today.

Shakespeare understood.

Why can’t we?

In Titus Andronicus, Lavinia is brutally raped and disfigured (including having her tongue cut out so she couldn’t speak). This nod to Philomela in Ovid’s Metamorphoses echoes the themes of the brutality of rape and the need for revenge. The women needed to name their rapists and share their stories (Lavinia writes in the sand; Philomela weaves a tapestry that tells her story). The women have as much power as they can in the confines of their society, and we the audience are meant to want justice and revenge.

Shakespeare’s epic poem The Rape of Lucrece also follows a young woman who is raped and seeks revenge (although her speech is left intact).

While the death of the women at the end of the plays seems problematic to 21st-century feminists, we must remember that in Shakespeare’s Roman fictions, self-sacrifice or honor killing was honorable and dignified, thus leaving the women with as satisfying an end as they could hope for. There are cultural differences, of course, but the anti-rape and anti-misogyny messages in these centuries-old texts are gripping.

In these texts, the following messages are clear:

• Rapists are depraved misogynists who want some kind of power.

• Silencing of women is evil.

• Women aren’t always allies (see: Tamora, who mothers and encourages Rape and Murder) .

• Retribution is necessary for justice.

Four-hundred years later, we still can’t seem to grasp these realities.

We look to media for social norms and values. If we see objectification of women on screen, we can clearly see the if this objectification has deeper feminist implications if we are supposed to villainize the objectifiers. (This is, incidentally, why the sexism in The Big Bang Theory makes my skin crawl and Sons of Anarchy–in all of its vengeful Shakespearian glory–is one of my favorite shows.) Shakespeare’s women–who are victims of violent patriarchies–are the ones the audience is supposed to sympathize with. The tragedy of these tragedies is that this patriarchal social order creates hell on earth for many women.

At the beginning of Titus, Lavinia pours a vial of her tears in her father’s honor as he returns home from war. She mourns and rejoices with him and is able to express her emotions surrounding his losses and his victories.

Mourning with him comes naturally. It’s what we expect when men encounter battles.

And just as Marcus says that they must mourn with Lavinia, she must not withdraw, we need to learn to mourn with those whom rape culture affects so deeply.

Four-hundred years later:

• Rapists are still misogynists who do not want sex, but want power.

• Women are still silenced. (And when they speak out, it is not without consequences.)

• Women still aren’t always allies.

• Retribution is still necessary, although we must fight to see it happen (and rely on online hackers and internet outrage to open up cases). Far too often we must wait for justice, if it ever comes.

When we can look to fiction from centuries ago and see common and familiar–almost radical–representations of the violent outcomes of restrictive patriarchies, we are doing something wrong.

Because the masses still don’t seem to understand that patriarchy hurts women. Patriarchy kills women.

Patriarchy is rape culture.

See also at Bitch Flicks: The Fractured Rape/Revenge Fantasies of Julie Taymor’s Titus

__________________________________________________________

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature, and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.