This guest post by Sophie Besl appears as part of our theme week on Rape Revenge Fantasies.

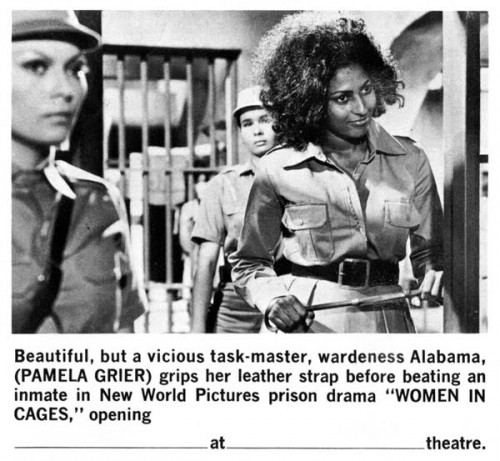

I got into exploitation films through Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill. I liked the Bride’s unapologetic rampage, and was thrilled to learn that Tarantino’s work emerged from a rich tradition of female-fronted films starting in the early 1970s. What interested me most was that this tradition was created by men for the entertainment of a predominately (young, urban) male audience. Yet these exploitation films, such as Coffy, Foxy Brown,[1] Lady Snowblood,[2] and dozens of low-budget slasher films[3] where the “last man standing” was almost always a woman, felt like some of the most empowering, pro-women films I had ever seen. No subgenre of exploitation films brings up the question of whether these films empower or exploit more so than the rape revenge genre. While there is evidence on both sides, as a feminist woman, I greatly enjoy films that follow this plot formula, seeing them as explorations of women’s potential to be fierce and powerful in the face of horrific abuse.[4]

I Spit on Your Grave, originally released as Day of the Woman[5] in the late 1970s, is to me the flagship film of the rape revenge genre. A woman named Jennifer rents a house in the country to spend some quiet time to herself writing and relaxing, but is trapped, tormented, raped, and almost killed by a group of four men from the small town. She then plans and exacts gruesome revenge on each of them. The film was torn apart by critics, yet decidedly not from a feminist angle. A review decrying the scene where Jennifer castrates one of her rapists as “one of the most appalling moments in cinema history,”[6] also calls out the double standard of sexual violence in film–rapes in other films, or even the rape of Jennifer earlier in the same film, did not rile up even close to the same level of distaste at the time it was released.

But while reviews were mixed for an understandably disturbing horror/exploitation film, this film importantly caused viewers to identify with a rape victim in ways previous films did not allow. In her book Men, Women, and Chain Saws, Professor Carol Clover suggests that I Spit on Your Grave is an example of the movement away from how rape was treated in films prior to the 70s, which typically caused the viewer to adopt the rapist’s point of view, such as with somewhat titillating close-ups of a woman’s face as she is strangled.[7] In this film, the viewer adopts Jennifer’s perspective. The camera reveals the ugliness and uncouthness of the male perpetrators from her point of view, and the acts are depicted in such a violent and unpleasant way that there is little discernable sexuality in the assaults. The filming reverses prior conventions in a way that could cause even male viewers to side with the victim rather than the rapists.

Another element that enables male viewers to identify with Jennifer is her victim-to-hero character, not commonly seen fully realized in female characters. Films from earlier in the century tend to have “victim” and “avenger” as separate characters—and often female- and male-gendered, respectively—but in rape revenge films, these roles are unified in one character. Without the “assumption that all viewers, male and female alike, will take Jennifer’s part, and…‘feel’ her violation…the revenge phase of the drama can make no sense” (Clover, 1992). If viewers want to cheer for Jennifer as a hero in the second half of the film, then they have inherently sided with her during her victimization in the first half.

Other than these new and progressive ways of considering female rape victims in film, I Spit on Your Grave provides three fantastic and thought-provoking elements:

The entire movie operates outside the realm of the law

Unlike many other rape revenge films (such as Last House on the Left, where the rapist is a criminal actively hunted by police; The Accused, which is entirely about the legal system and rape; or even the 2010 remake of I Spit on Your Grave, where one of the four men is a police officer), I Spit on Your Grave takes place without any sign of law enforcement. Jennifer does not go to the police after her attack. There is an interesting scene where she prays briefly at a church, but mostly the film recounts, somewhat objectively, the play by play of her attack, followed by the play by play of her revenge killings (though the trailer does proclaim “There isn’t a jury in this country that will convict her!”). No movies ever had to justify a cowboy going on a rogue revenge kick after his log cabin was burned to the ground or his family was killed; certain sufferings of injury, murder of loved ones, robbery, etc., have been accepted throughout cinematic history to merit revenge at all costs. I Spit on Your Grave was a large part of a relatively new phenomenon, possibly born out of the feminist movement, to add rape—based on the woman’s experience of rape, whether validated by law or not—to that list of worthy harms, which is an important statement in our rape culture.

Jennifer uses feminine seduction to exact her revenge

In rape revenge films, the feminine experience of rape often, notably, is the cause for the hero-victim to take on masculine qualities, such as low emotionality and physical brutality. However, in I Spit on Your Grave (while she is undoubtedly brutal in committing murder), Jennifer gets her first “victim” by softly entreating him, “I’ll give you something to remember for the rest of your life.” She actually begins to have intercourse with him (interestingly, he was the only one of the four men who did not want to assault her—he had been a virgin, is cognitively challenged, and caves to peer pressure) so she can slip a noose around his neck and hang him. She simply drives up to her next “victim” and beckons him into her car. He goes willingly because he believes she wants some more. When she pulls a gun on him, he tries to talk her out of shooting him. She complies and invites him back to her house, which he also willingly does due to her coy demureness. At her house, they take a bath together, and while touching him underwater saying, “Relax, I’ll make you feel like you’ve never felt before,” she subtly slips a knife into the tub and cuts his genitals off. Jennifer swims up to the next man’s boat in her bikini and seductively climbs in. Caught off guard, he is pushed into the water, and Jennifer kills him and the last man with an axe and the boat’s motor as they flounder. Her sexuality is her means of entering the situations that enable her to execute each man.

I find it interesting that the castration scene was removed in the remake (as was another such scene in the remake of Last House on the Left), and I’m not sure why. Castration seems to be on an equal plane with the level of violence in these films. (Was it too distasteful to male viewers? Something to think about.) There is also no seduction during the revenge in the remake, with Jennifer instead relying on torture/murder tactics similar to the Saw movies. While perhaps this rewrite to agendered violence is feminist in that she can use the same cunning, engineering, and brutality as men, I think the significance of 1978’s Jennifer using female sexuality, the root of her attack, as part of her revenge technique should not be overlooked.

All four of the men must die, no matter their physical role in the gang rape

During their attack on Jennifer, three of the men constantly “offer” her to the cognitively challenged man, who is visibly horrified by what his friends are doing and avoids participating at all costs. The other three men commit different acts trying to impress and show off to one another, sickly showing that this is more of a sport or game to them than a sexually driven act. When Jennifer confronts each man alone, he pleads and blames the other men. The group dynamic may have caused the men to do things they otherwise wouldn’t have, and the film could serve as a sick warning to men in our rape culture. However, it is important and noteworthy, especially because some reviews at the time described “three rapes” and “three rapists,”[8] that there is no doubt in Jennifer’s or the viewer’s mind that all four should be punished.

I don’t believe the anti-feminist trope that women need attacks like this to make them strong. Many of these films involve gang rapes, or other situations where the woman is at a serious disadvantage due to the men’s weapons or physical strength. To me, the message in these films is that if men choose to take advantage in these sick ways, they will be punished beyond their imagination. A common question is, What do men get out of watching these films (made for men, by men)? I think, because rape is based in extreme powerlessness, degradation, and humiliation, it gives audiences a free pass to fully experience and enjoy the revenge half of the film. In a rich history of movie characters avenging murders of loved ones and all types of suffering, the rape revenge fantasy should only take second place to someone being able to avenge their own murder. Anything the media or society can do to enforce the idea that rape is a paramount crime is a step in the right direction, and I Spit on Your Grave played a large role in building that case through film.

See also at Bitch Flicks: Rape as a MacGuffin: The Hollywood Cop Out

Recommended reading: I Was Wrong About I Spit on Your Grave

Sophie Besl is an exploitation film fanatic with a day job in nonprofit marketing. She has a Bachelor’s from Harvard and lives in Boston with her feminist boyfriend and three small dogs. She tweets at @rockyc5.

[1] Coffy (which Tarantino cites as a direct precursor to Kill Bill) and Foxy Brown, both star Pam Grier, a darling of Blaxploitation whom Tarantino later directed in Jackie Brown. (For more on the fantastic Pam Grier, please read these Bitch Flicks articles on her unfinished legacy and her time in another exploitation subgenre, women in prison). A similar discussion of racism is relevant with Blaxploitation movies—while these films use excessive nudity and do confirm stereotypes, they star Black protagonists who are in themselves empowered in fighting personal battles, and viewers of all backgrounds identify with these protagonists.

[2] Lady Snowblood stars a fierce female protagonist, and is part of the chambara subgenre of exploitation, a revisionist, non-traditional style of samurai film popular in Japan in the early 1970s (Wikipedia).

[3] Slasher films are an exploitation and horror subgenre. While they too are arguably feminist, in that the murderer is usually defeated by the “Final Girl,” in these films, the female protagonist fights because she has to. Rape revenge plots have women calculate revenge, then choose to engage in violence as an avenger, rather than a continuation of being a victim.

[4] When a female character is the attacked avenger, I prefer films that focus on rape revenge fantasy as the entire plot, as opposed to a story like The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, where it is a part of a larger story. A story where it is simply part of the plot sends me the message that rape is part of what women have to deal with on a daily basis; it is inescapable. The extreme treatment of and sole emphasis on rape in films like I Spit on Your Grave and Last House on the Left enables these films to be an exploration of power plays and humanity’s darker sides, rather than a statement about the prevalence of rape in women’s lives.

[5] The original title of this film is significant. The “day of the woman” to me clearly refers to the day of her vengeful murders. By using the phrase “the woman” instead of the character’s name, this seems to imply that her revenge is not just on behalf of herself against her attackers, but on behalf of all women against all men who have perpetrated crimes like this.

[6] Review from Mick Martin and Marsha Porter, Video Move Guide: 1987, as cited and described in Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, by Carol J. Clover (Princeton University Press 1992).

[7] See Clover (1992, p. 139) for more. She argues that, in films made before 1970, rape was “construed as an act of revenge on the part of a male who has suffered at the hands of the woman in question (to have been sexually teased, or to have a smaller paycheck or lesser job, is to suffer).”

[8] Clover, 1992.