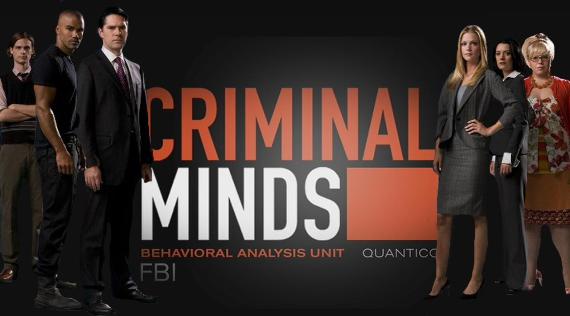

|

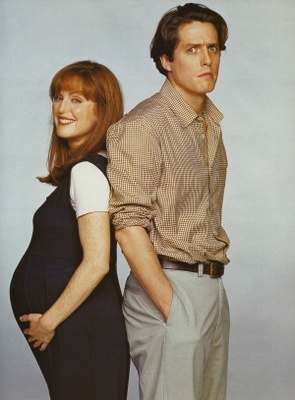

| Julianne Moore and Hugh Grant in the film Nine Months |

This is a guest review by Tyler Adams.

Male Pregnancy

Nine Months, contrary to all expectations, is not about pregnancy. It’s about a man coping with a pregnancy. Yes. Here’s a film whose subject absolutely and biologically requires a woman – and it’s still about a man.

However, Nine Months does achieve sex equality of the most dubious sort – it’s insulting to men and women.

In the world of Nine Months, women have already accepted that their value lies primarily in their fecundity and that raising children is the only thing that matters. And now, it’s time for men to learn the same lesson.

Rebecca, whose unplanned pregnancy kick-starts the plot, knows full well the consequences of pregnancy. And she ignores them. She wants to keep the baby, immediately, after about five minutes of running time where she isn’t even onscreen.

To the film’s credit, it doesn’t demonize Rebecca for subtly, whisperingly alluding to abortion, but the film glosses over it too much to truly be considered ‘pro-choice.’

The conflict in the film’s first act is all about Samuel accusing Rebecca of getting pregnant on the sly. Yes. She tells him she’s pregnant and he turns it into an act of aggression against him. He blames it on her: condescendingly scoffing that birth control could be anything other than foolproof.

Then we get delightful dream sequences wherein Samuel imagines Rebecca as a praying mantis trying to eat him.

As Anita Sarkeesian points out in her excellent video ‘Tropes vs. Women: The Evil Demon Seductress,’ most praying mantis species don’t engage in sexual cannibalism. And neither do women. Except to adolescent men terrified of female sexuality.

Then there’s Samuel’s friend Sean, our childfree Straw-man. His girlfriend says she wants kids, she leaves when he says ‘no’ – a week later, he’s self-admittedly using another woman to ‘get him over the rough spots.’ He describes her breasts, calves, and skin like food, basically making her sound like a golem made of calzones, candy, and cake.

Bobbie, his ‘girlfriend’ is a stereotypically attractive young woman who literally never says a word during the whole film and has no narrative purpose other than temporary eye candy – so the film treats her about as well as Sean does. With Sean, the filmmakers are essentially equating child-freedom with misogyny. Hey, all women want kids, so not wanting to have kids means being anti-woman, right?

There certainly aren’t any major single, childfree, or independent women in the film. Gail is the only other main adult female character, and she has three daughters and one on the way. She talks to Rebecca about how ‘pregnancy is our profound biological right, something men can never experience,’ when Rebecca expresses her one, solitary note of doubt in the film (in a conversation that doesn’t even pass the Bechdel Test, given that it’s all about men and childbirth). This is pretty much the only time the film really deals with Rebecca’s perspective in a way that doesn’t relate to Samuel.

The idea is that it’s a woman’s duty to have children, which is ‘natural’ and therefore good, and a source of female privilege. Gail even frames this in feminist terms, as if Karen Horney’s ‘womb-envy’ concept was a step forward for gender equality (Enlightenment-era chauvinists celebrated women’s fecundity, too – Enlightenment-era feminists spent more time talking about women’s rights), and there’s anything empowering about the idea that women absolutely must have children regardless of their personal feelings, because, apparently, it’s the one advantage they have over men.

Rebecca calls independent single motherhood ‘fashionable,’ and ‘PC,’ basically dismissing it. She says she would rather have a family – as if a single parent family doesn’t count. All Samuel has to do is propose. Why she doesn’t just pop him the question is unexplained. Apparently, even the audience takes it for granted that that’s the man’s decision to make.

Nine Months is trying to celebrate motherhood through the eyes of a reluctant father. Rebecca’s feelings are barely addressed, and Gail doesn’t seem to know how to celebrate motherhood without also demeaning the childfree. She says of Samuel, ‘You have a baby, that means he’s gotta grow up. That’s what he’s afraid of. I mean, the baby’s the fun part…Look at all this stuff.’

She’s referring to the toy store merchandise. Yes. Apparently the joys of motherhood are not bonding with and nurturing other human beings, but buying them things. Gail has the ultimate conservative vision of motherhood – it combines chauvinism and capitalism!

Professional Parents

“What if the baby can see…your penis, coming toward it, that could scare the hell out of a baby…or what if your penis hit it in the head; it could cause brain damage…”

I’m not embellishing. That’s what Rebecca says, five months into her pregnancy, right before she and Samuel have sex. Rebecca is in her thirties, and – well, given the number of biological errors she made in two lines, I’m terrified of what else she doesn’t know about things you should and shouldn’t do during pregnancy.

What does it say about the state of women’s health education that this scene does not read as satire? And if it was supposed to be funny, well – maybe it could work as horror comedy, but I didn’t see any real commentary.

By the way, it should be mentioned that Samuel is a child psychotherapist. Or ‘kiddy shrink’ as Gail calls him. He’s a child psychotherapist and doesn’t know the first thing about pregnancy. He doesn’t know that amniotic fluid in the uterus protects the baby, and the cervix is blocked throughout most of a pregnancy, or you’d think he would have told Rebecca about it during their attempted sex scene.

He’s allegedly successful at his job, but all we see is his being clueless around children, insensitive around women, and ignorant about everything he should be an expert on. The man has to read a book like What to Expect When You’re Expecting, as if he’s never taken any classes on prenatal development. Well, he didn’t know that birth control is only 97 percent effective, so let’s just assume he’s never even taken sexual education at school.

We do see a competent, female gynecologist who more or less helps set Samuel on the right path, but for some reason, we spend a lot more time with bumbling Russian stereotype Dr. Kosevich. All the better to humiliate Rebecca with, I suppose, during her first doctor’s appointment, and later, during the world’s most farcical labor scene where Samuel nearly kills several people trying to get her to the hospital. Oh, and he starts a fistfight during her delivery. How you advocate birth while making it look horrible and playing it for juvenile laughs is anyone’s guess.

Marty and Gail are ultimately the people Rebecca and Samuel turn to for advice. No matter how poorly socialized their daughters are, they’re experts. A child psychotherapist like Samuel has to ask Marty and Gail for help, and as far as the narrative goes, they outrank a gynecologist. Even though Marty believes that you can tell the fetus’s gender by whether the mother’s carrying high or low, and that sexual positions influence sex determination. Although, the anti-intellectualism works well with the film’s overall sneering at creative and professional individuals.

Sean: “…the world is overpopulated; our society has too many starving children.”

Gail: “Well, I would say our society has too many starving artists…this was our parents’ home, but I don’t see you making any contribution…you keep this up you’ll die alone, like a dog, like a bum. Like Van Gogh.”

Sean is an artist, and Gail demeans him for it, because hey, we all know art doesn’t pay. Not like owning a car dealership like Marty, which is a much better contribution to society, of course.

Of course, Sean’s work seems irrelevant. Since he doesn’t ‘have’ a wife and kids, he’s not making any meaningful contribution to the world at all, according to Gail. She equates being single with being isolated, and being childfree with being childish. And the film takes her side.

When Sean argues that she and Marty used to have interests, and are now just obsessed with their children, she doesn’t even deny it. She just affirms that this is the way it should be. After all, earlier Rebecca instantly accepts that she has to quit her job as a dancing instructor – not just take a leave of absence; actually quit. Samuel, after his transformation, says ‘I don’t give a damn about me; I’m in love with my child.’ Apparently, parents of all genders should be denied personhood outside their children, and this is something all women want, and all men should want.

Girl Children

|

| Ashley Johnson as Shannon Dwyer in Nine Months |

Marty goes shopping for sports equipment as he’s assuring Samuel he’s having a boy, on no evidence. Apparently, all boys must be into sports, or they’ll be forced to be, and none of Marty’s daughters are athletes or could be.

When Samuel shows his distaste for being hit in the face or punched in the stomach by Marty or his daughters, Marty and the film insult Samuel’s masculinity. Especially when the daughters do it. When Marty gets into a fight with some Barney stand-in over some petty insults, Samuel doesn’t join in until he’s accused of being gay. It’s okay to be genuinely childish, apparently – like beating someone up in public over petty insults – as long as you look appropriately ‘masculine’ while doing so.

When Marty learns he’s having another girl, he complains (at the end, he relents and says, “I guess having another girl isn’t so bad.” Bravo.), and Samuel smirks about his good fortune in getting a boy. Earlier in the film, one of the reasons Samuel comes around and accepts the pregnancy is learning his child is a boy. The film obviously doesn’t value girls any more than it values women.

Samuel’s character arc is not about him overcoming his sexism – it’s about him ‘growing up’ by accepting fatherhood. When he reunites with Rebecca, he says he’s in love with his son, and is in love with her for having him – in love with her as a vessel, not a person, as Eve Kushner at Bright Lights Film Journal astutely observed. He never really misses her when she’s gone, never really asks how she’s feeling, or even has a real conversation with her – when he comes around, he comes around for the baby and not for her.

The film isn’t subverting the tropes that women, family, and children force men to lose personalities, that all women are content to be homemakers, that losing your personality is part of growing up, or that all people’s worth lies in childrearing – the film is just positively endorsing it all.

There’s nothing inherently bad about having children or getting married. One of the problems comes from the sentiment that you need a spouse and kids regardless of personal taste, or even regardless of the spouse and kids. The way many people talk about this is roughly: get a woman, or get a man, or get some kids. Any will do, apparently.

Children are not your unique children you can nurture and bond with – they’re just a burden that forces you to nobly suffer and mature. Marriage isn’t an outgrowth of a loving relationship between two complete individuals, it’s just an item on your life’s agenda to be crossed off, and establish you as an adult with a life worth living. Your spouse and children exist as objects related to you, and since that’s what you were looking for, that’s what you got.

It’s an attitude that not only reduces acceptable lifestyles down to practically nothing, but degrades the lifestyle it should be promoting. It’s a recipe for unhappy children, and unhappy marriages. Good thing Nine Months stops shortly after the nine months, and we don’t see our couple’s future. What we’ve seen – Samuel’s sullen patients, Marty and Gail’s children, as well as Marty and Gail – are evidence enough.

———-

Tyler August Adams is a Master’s candidate in Environmental Science and Policy, and writes decidedly unconventional reviews and reflections on the media at http://nevermedia.blogspot.com.