Written by Max Thornton.

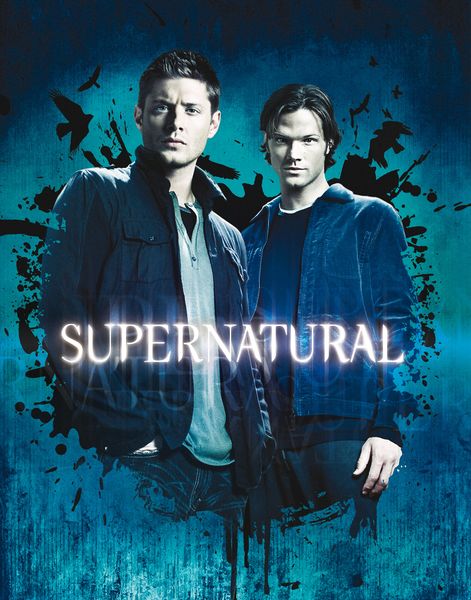

Early in my embarrassingly emotional addiction to Supernatural, a friend pointed out that Supernatural picks up right where Buffy the Vampire Slayer left off – not only chronologically, having begun just two years after Buffy ended, but also in terms of the characters’ ages and stages in life. The Buffy gang took us demon-slaying through high school and college, while the Supernatural boys launch us on a quarter-life-crisis monster hunt as a career.

Both shows use a campy sensibility to explore questions of family, loyalty, and identity through monster metaphors. Both were resurrected after a self-contained five-season run to flounder a bit in seeking direction for continuing. Both have passionate fanbases who love to overanalyze every detail of the show.

Unfortunately, the major distinction between them arguably reflects a disturbing turn in US society at large: from the ongoing war on reproductive agency to the escalating violence against trans women, misogyny seems to be on the uptick.

It would, of course, be disingenuous to claim that the Joss Whedon brand of feminism is above reproach. We’ve covered the issues here at Bitch Flicks many times before, but the fact is, everything we criticize Whedon for – his failings with respect to race, sexuality, gender – is dialed up to 11 in Supernatural.

There’s a certain charmingly riot-grrrl sensibility about the fabled origin of the concept for Buffy, Whedon’s well-documented desire to subvert the horror-movie cliché of the petite blonde victim by turning her into the superhero who punches monsters and stabs vamps. Ongoing critique of the whole “strong female character” trope problematizes the simplicity of this image, but only the most determined of naysayers could deny that Buffy Summers is a truly well-rounded, three-dimensional female character.

Supernatural, by contrast, has absolutely no feminist ambitions whatsoever. It’s a show about two estranged brothers reuniting to spend (at least) a decade working through their vast and multitudinous daddy issues by hunting and killing demons. The hunter substratum in which Dean and Sam Winchester operate is pretty traditionally macho, featuring a lot of roadtripping around the lower 48 in a ’67 Chevy Impala, listening to classic rock, being emotionally unavailable to an identikit parade of conventionally attractive women, and bottling up secrets from each other until they emerge at the most inconvenient possible moment for a melodramatic climax of raw fraternal honesty and man-tears.

The simplistic machismo of Supernatural is particularly frustrating because there is so much potential for the show to challenge the norms of conventional masculinity – and yet it just doesn’t.

After its first few seasons, which were more broadly monster-centered, Supernatural has turned its focus heavenward, to the metaphysical ministries of angels and demons. Now, a show that poaches so liberally from every belief system it’s ever met should be able to have some fun here with sexuality and gender. Angels in much of Christian tradition are ungendered beings of pure spirit, so it would make sense for the show’s angels to routinely transgress gender norms in the human bodies they take on as their vessels. It would be a great way to portray the angels’ non-humanity, showing them unwittingly and uncomprehendingly steamrolling over human gender roles because they simply do not know or care about this petty aspect of human life.

Alas, the show takes the lazy way out, adhering to the most narrowly patriarchal interpretation of angel gender. Most of the important angels are male, the female ones are seductive temptresses, and there’s no crossing or blurring of gender boundaries.

This is especially egregious, because the UST between Dean Winchester and the angel Castiel is off the charts. “Destiel” is Tumblr’s favorite romantic pairing, and it’s not hard to see why.

The chemistry between actors Jensen Ackles and Misha Collins could lay the foundation for corroboration of Dean’s obvious yet canonically unacknowledged bisexuality, for an in-depth exploration of angelic nature, for a thorough dismantling of the gender binary… but of course absolutely none of that has happened. Instead, the show has taunted fans with an ongoing equilibrium of cynical queerbaiting, while acting as though a handful of episodes featuring a nerdy redheaded lesbian femme constitutes sufficient compensation.

Supernatural‘s other greatest sin is its wanton murder of female characters. Buffy may have come under a lot of criticism for fridging a beloved female character, but Supernatural winkingly lampshades its tendency to fridge women as if that somehow makes it okay.

I won’t pretend I don’t love Supernatural – I’m the middle of three brothers, so it always had me on that count alone – but I also can’t pretend that it’s not a profoundly, epically, perhaps fatally flawed show. I’ll watch the forthcoming tenth season, and I’ll hope that it gets better, but I know better than to hold my breath.

_______________________________________

Max Thornton blogs at Gay Christian Geek, tumbles as trans substantial, and is slowly learning to twitter at @RainicornMax. He wishes he knew how to quit Supernatural.