Here at

Bitch Flicks, we’re super excited by the 3rd annual

Athena Film Festival! We’ve attended each year, watching fearless and inspirational women on-screen and listening to brave and bold filmmakers. The festival features narrative films, documentaries, short films along with panels and workshops for filmmakers — all focusing on women’s leadership. Co-founded by Melissa Silverstein and Kathryn Kolbert, the festival runs from

February 7-10 in New York City at Barnard College.

Kathryn Kolbert, Athena Film Festival Co-Founder and the Constance Hess Williams Director of the Athena Center for Leadership Studies at Barnard College, said:

“We are proud to announce such a robust lineup for this year’s Festival. The variety of films and filmmakers at the festival this year exemplifies the increasing presence of female leaders in the industry.”

Melissa Silverstein, Athena Film Festival Co-Founder and Artistic Director and head of

Women and Hollywood, said:

“The balanced mix of films represents the breadth and depth of the Festival’s mission. Each year we strive to selectfilms that inspire filmmakers and industry members. This year’s slate is our strongest yet and continues to convey this focus.”

With only 5% of women directing films, female writers comprising 24% of all writers in Hollywood and women in only 33% of speaking roles in films, women’s experiences and perspectives are often missing. Women don’t just sit on the sidelines. They lead, advocate and inspire. The films featured at the Athena Film Fest celebrate women’s diverse lives yet their common goal to catalyze change.

Purchase tickets and passes here.

FEATURE FILMS

Beasts of the Southern Wild

Director: Benh Zeitlin

Run Time:

Language: English

In a forgotten but defiant bayou community cut off from the rest of the world by a sprawling levee, a six-year-old girl is in balance with the universe, until a fierce storm changes her reality. Buoyed by her childish optimism and extraordinary imagination, and desperate to save her ailing father and sinking home, this tiny hero must learn to survive unstoppable catastrophes. Hailed as one of 2012’s most original films, Beasts of the Southern Wild appeared on many critics year-end top 10 lists.

Brave

Director: Mark Andrews, Brenda Chapman

Run Time:

Language: English

Determined to make her own path in life, Princess Merida defies a custom that brings chaos to her kingdom. Granted one wish, Merida must rely on her bravery and her archery skills to undo a beastly curse.

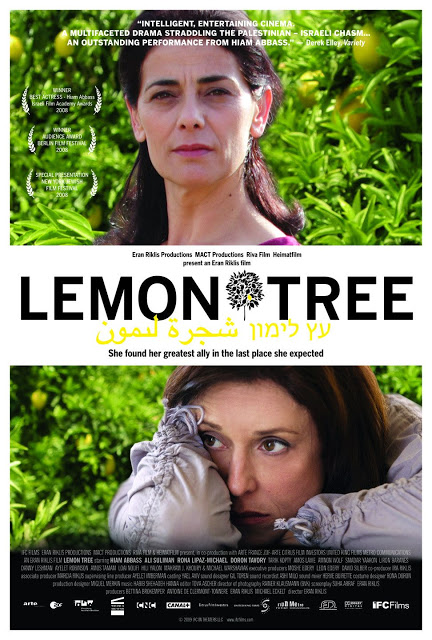

Fast Girls

Director: Regan Hall

Run Time: 91 minutes

Language: English

When a sassy streetwise runner meets an ambitious, wealthy competitor, their two worlds collide with explosive results. As the fast girls strive to qualify for the World Championships, they battle adversity and rivalry on a dramatic, heartwarming and inspirational journey.

Future Weather

Director: Jenny Deller

Run Time: 100 minutes

Language: English

Abandoned by her single mom, a teenaged girl becomes obsessed with ecological disaster, forcing her and her grandmother, a functioning alcoholic, to rethink their futures. Inspired by a New Yorker article on global warming, Future Weather uses the refuge of science and the environment as a backdrop as the two women learn to trust each other and leap into the unknown.

Ginger and Rosa

Director: Sally Potter

Run Time: 90 minutes

Language: English

London, 1962. Two teenage girls — Ginger and Rosa — are inseparable. They discuss religion, politics, and hairstyles, and dream of lives bigger than their mothers’. But, as the Cold War meets the sexual revolution, and the threat of nuclear holocaust escalates, the lifelong friendship of the two girls is shattered –by a clash of desire and the determination to survive.

The Girl

Director: David Riker

Run Time: 90 minutes

Language: English, Spanish with English subtitles

Emotionally distraught from losing custody of her son and running out of options to earn a living to win him back, single mother Ashley (Abbie Cornish) becomes desperate when she loses her job at a local Austin megastore. So when the risky opportunity arises to become a coyote—smuggling illegal immigrants over the Texas border—she takes it. The harrowing experience results in unforeseen rewards and consequences, as Ashley forges an intense bond with a young Mexican girl who forces her to confront her past, accept the mistakes she’s made, and look to the future.

Hannah Arendt

Director: Margarethe von Trotta

Run Time: 113 minutes

Language: English, German with English subtitles

Hannah Arendt is a portrait of the genius that shook the world with her discovery of “the banality of evil.” After she attends the Nazi Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem, Arendt dares to write about the Holocaust in terms no one has ever heard before. Her work instantly provokes a furious scandal, and Arendt stands strong as she is attacked by friends and foes alike. But as the German-Jewish émigré also struggles to suppress her own painful associations with the past, the film exposes her beguiling blend of arrogance and vulnerability — revealing a soul defined and derailed by exile.

Middle of Nowhere

Director: Ava DuVernay

Run Time: 97 minutes

Language: English

When her husband, Derek, is sentenced to eight years in a California prison, Ruby drops out of medical school to focus on ensuring Derek’s survival in his violent new environment. Driven by love, loyalty, and hope, Ruby learns to sustain the shame, separation, guilt, and grief that a prison wife must bear. Her new life challenges her identity, and propels her in new, often frightening directions of self-discovery. Winner of Best Director Award at 2012 Sundance Film Festival and Best Actor at the 2012 Gotham Awards.

La Rafle

Director: Roselyn Bosch

Run Time: 115 minutes

Language: French, German, Yiddish with English subtitles

This film is the story of the infamous Vel’ d’Hiv roundup in 1942 when French police carried out an extensive raid on Jews in greater Paris, resulting in the arrest of more than 13,000 people — including 4,000 children. Told from the perspective of the children and the nurse who cared for them, this is an emotionally astute and sensitive exploration of a long taboo subject in France — one that caused former French President Jacques Chirac to issue a public apology in 1995.

Violeta Went to Heaven (Violeta Se Fue A Los Cielos)

Director: Andrés Wood

Run Time: 110 minutes

Language: Spanish and French with English subtitles

This is the extraordinary story of the poet and folksinger Violeta Parra, whose songs have become hymns for Chileans and Latin Americans alike. Director Andrés Wood traces the intensity and explosive vitality of her life, from humble origins to international fame, her defense of indigenous cultures, and devotion to her art.

DOCUMENTARIES

Band of Sisters

Director: Mary Fishman

Run Time: 88 minutes

Language: English

The work of two nuns outside a Chicago-area deportation center introduces us to the tumultuous and engaged world of U.S. Catholic nuns in the fifty years following Vatican II. From sheltered “daughters of the church” once swathed in medieval dress to activists for social justice, Band of Sisters follows the journey of these religious women as they work for civil rights, and immigration reform, and become increasingly relevant and visible in aid of the poor and disenfranchised.

Birth Story: Ina May Gaskin and The Farm Midwives

Director: Sara Lamm and Mary Wigmore

Run Time: 95 minutes

Language: English

Birth Story: Ina May Gaskin and The Farm Midwives captures a spirited group of women who taught themselves how to deliver babies on a 1970s hippie commune. They grew their own food, built their own houses, published their own books, and, as word of their social experiment spread, created a model of care for women and babies that changed a generation’s approach to childbirth. Today, as nearly one-third of all U.S. babies are born via C-section, they labor on, fighting to preserve their knowledge and pushing, once again, for the rebirth of birth.

Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has To Travel

Director: Lisa Immordino Vreeland

Run Time: 86 minutes

Language: English

The legendary Diana Vreeland was the arbiter of the fashion world for four decades. From her early days as a columnist at Harper’s Bazaar to her eight-year reign as Editor-in-Chief at Vogue beginning in 1963, Vreeland’s larger-than-life personality and flair for the slightly outrageous gave her the final word in pushing fashion forward.

Granny’s Got Game

Director: Angela Alford

Run Time: 74 minutes

Langauge: English

Granny’s Got Game tells the story of six fiercely competitive women in their seventies who battle physical limitations and skepticism to keep doing what they love. The film follows the inspiring women for a year as they compete for another National Senior Basketball Games Championship.

Inocente

Director: Sean Fine and Andrea Nix Fine

Run Time: 40 minutes

Language: English and Spanish with English subtitles

At 15, Inocente refuses to let her dream of becoming an artist be thwarted by her life as an undocumented, homeless immigrant. The extraordinary sweep of color on her canvases creates a world that looks nothing like her own dark past — punctuated by a father deported for domestic abuse, an alcoholic and defeated mother of four, an endless shuffle through San Diego’s homeless shelters, and the constant threat of deportation. Neither sentimental nor sensational, Inocentewill immerse you in the very real, day-to-day existence of a young girl who is battling staggering challenges. But the hope in Inocente’s story proves that the hand she has been dealt does not define her, her dreams do.

I Stand Corrected

Director: Andrea Meyerson

Run Time: 84 minutes

Language: English

Watch Jennifer Leitham perform and it’s obvious the striking redhead is an original. When this world-famous jazz bassist takes center-stage, she’s a special talent made all the more unique because Jennifer Leitham began her life and career as John Leitham. I Stand Corrected explores Leitham’s enlightening story of success and survival, of betrayal and compassion, and the risks she takes to embrace who she truly is.

Putin’s Kiss

Director: Lise Birk Pedersen

Run Time: 85 minutes

Language: Russian with English subtitles

Putin’s Kiss portrays contemporary life in Russia through the story of Masha, a 19-year-old girl who is a member of Nashi, a political youth organization connected with the Kremlin. Extremely ambitious, the young Masha quickly rises to the top of Nashi, but begins to question her involvement when a dissident journalist whom she has befriended is savagely attacked.

Women Aren’t Funny

Director: Bonnie McFarlane

Running Time: 78 minutes

Language: English

Female comedian Bonnie McFarlane sets out along with fellow comedian and husband Rich Vos (and their adorable 3 year old) to find out once and for all if women are funny and report her unbiased findings in this important documentary film. Working around stand up gigs, quarrelling with her husband and parenting their daughter, Bonnie manages to squeeze in interviews with a wide range of comedians, club owners, talent bookers and writers about why there remains such a pervasive, negative stereotype about women in comedy.

WONDER WOMEN! The Untold Story of American Superheroines

Director: Kristy Guevera-Flanagan

Run Time: 62 minutes

Language: English

Tracing the fascinating evolution and legacy of Wonder Woman and superheroines in film from the birth of the comic book superheroine in the 1940s to the blockbusters of today,

WONDER WOMEN! examines how popular representations of women reflect society’s anxieties about women’s power and liberation. Goes behind the scenes with Lynda Carter, Lindsay Wagner, comic writers and artists, and real life superheroines as well.

SHORT FILMS

Shorts Program 1

Shorts Program 2

Shorts Program 3

Works in Progress

PANELS AND DISCUSSIONS

A Hollywood Conversation with Gale Anne Hurd

Hear from this year’s winner of the Athena Film Festival’s Laura Ziskin Lifetime Achievement Award, Gale Anne Hurd, as she discusses her career and experience as one of the industry’s most respected and innovative film and television producers. Hurd has developed and produced films that routinely garner Academy Award nominations, and TV programs that win Emmys and shatter ratings records. She has carved out a leading position in the male-dominated world of the blockbuster, and become a recognized creator of iconic cultural touchstones including the blockbuster cable hit, The Walking Dead, and such iconic films as The Terminator, Aliens, The Abyss and Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

In Her Voice: Women Directors Talk Directing

In Her Voice is the first book to ever take the words and experiences of celebrated women film directors and put their voices front and center. This unique volume of interviews presents more than 40 feature and documentary directors from around the world including Debra Granik (Winter’s Bone), Courtney Hunt (Frozen River), Callie Khouri (Mad Money), Sally Potter (Rage), Lone Scherfig (An Education) and Lynn Shelton (Humpday).

Sundance Institute Presents: Women Directors in Independent Film

The Sundance Institute has partnered with Women and Film to examine the submissions and selections for the Sundance Film Festival and for Sundance Institute Feature Film and Documentary Film Programs to determine whether gender makes a difference. After examining data from multiple years, the research identifies systemic obstacles that hinder women directors at key stages in their independent film careers. The research was released at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival. Keri Putnam, Executive Director of the Sundance Institute will participate in the discussion.