I don’t want my role on this website to be that of some gross White Knight, the dude constantly defending (largely female) fandom as if fans are incapable of standing up for their pretty little lady selves. But I do want to talk about fandom a lot, because the broader culture denigrates fandom in a way that is not, I think, unconnected to the (perceived) female dominance of fandom (*COUGH* MOFFAT *COUGH*), and I truly believe that fandom is a really important space for carving out counterreadings.

I only started watching NBC’s Hannibal because of Bryan Fuller. Fuller created Wonderfalls and Pushing Daisies (and Dead Like Me, which I swear I will watch one day; please don’t let it ruin my credibility that I haven’t gotten to it yet), which are shows that seem tailor-made for me: they are charming and colorful and quirky and witty and delightsome, shows with a supernatural element and a slightly twisted edge and totally rad female characters. Much as I loved Silence of the Lambs when I was an angsty (and deeply closeted trans) teenager, I wasn’t at all sure how well the good Dr. Lecter would lend himself to the Fuller aesthetic, but it’s turned out quite interesting.

The aesthetic is definitely the most striking thing about the show. You’ll see it described in terms like sumptuous, operatic, Lynchian, bombastic. It’s a show that is deliberately dreamlike, blurring the distinction between fantasy and “reality” (where the reality is, of course, itself a fiction), exploring the beauty of horror in a febrile dream of refined grotesquery. It’s not, perhaps, traditionally “girly.”

The cast is also noticeably more male-dominated than Fuller’s previous shows. Even though IMDb’s cast listing suggests that Beverly Katz (Hettienne Park) and Alana Bloom (Caroline Dhavernas, or as she’ll always be to me, Jaye Tyler) are just as prominent as Hannibal and Will Graham, this is really not the case. Katz and Bloom are both pretty awesome, and the choice to genderflip the book’s Alan Bloom was a very good one, but they are definitely backgrounded in comparison to the main dudes.

I like the show fine, but to be perfectly honest I like the fandom more. The fandom is the thing that’s keeping me engaged. Fuller himself expresses it nicely in this Entertainment Tonight interview:

I was surprised at the demographic that the show was reaching. A significant portion was young, smart, well-read women; they really responded to this show and I typically relate to young, bright ladies [laughs]. It was nice to see how enthusiastic and passionate they were. And, also, happy in the face of the dark material. They found joy and hope in something that is arguably quite bleak. I found that really rewarding and as somebody who is a fan of many things myself, I appreciate and relate to being enthusiastic about a show you love. I think it’s wonderful.

One example of what Fuller’s talking about is the whole flower crown incident of 2013. Last year, for whatever reason (can you fathom the mysteries of memes?), the fandom started photoshopping flower crowns onto pictures of the Hannibal cast. The joke spilled over into real life at Comic-Con, where the show’s cast and crew wore actual flower crowns.

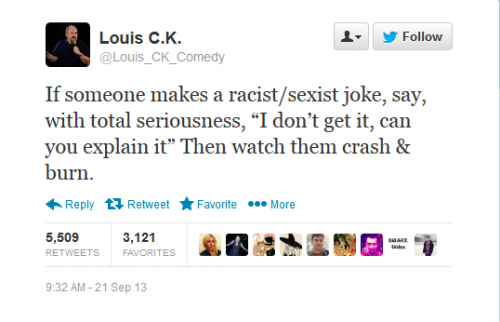

Then, of course, there is the inevitable shipping. Fans love their “Hannigram,” the proposed romantic pairing of Hannibal Lecter and Will Graham. Canonically, the relationship between Lecter and Graham is certainly intense and obsessive, but it’s fair to say that it’s not really sexual. Fuller’s reponse to the shippers is wonderful.

He’s gracious and respectful, recognizing that slash is an important creative outlet for a lot of people, and opening space for it to exist as a kind of paratextual AU with canon’s blessing. Bryan Fuller is the best at having fans.

The Hannibal fanbase has taken something potentially very twisted and grotesque, and reshaped it into something charming and cuddly, focused on love and flowers and puppies. That in itself is very Bryan Fuller, and it’s also something I find very delightful and redemptive. I think the (young, female) Hannibal fans are doing a really cool counterreading that’s extremely needed by our violence- and crime-obsessed culture. Long may it last.

____________________________________________

Max Thornton blogs at Gay Christian Geek, tumbles as trans substantial, and is slowly learning to twitter at @RainicornMax. You can donate to his surgery fundraiser here.