This post by staff writer Sarah Smyth appears as part of our theme week on Demon and Spirit Possession.

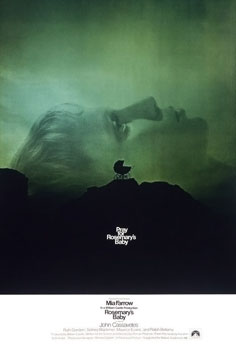

Who possesses the pregnant woman’s body? In Roman Polanski’s 1968 film, Rosemary’s Baby, the answer is twofold. The film’s titular protagonist, Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow), becomes physically possessed after she becomes pregnant with a demonic Devil child. Yet, this heightened and fantastical narrative allows for a broader discussion regarding the wider possession of the pregnant women’s body as Rosemary becomes intensely scrutinised, manipulated, and controlled by outside forces. Rosemary is not only possessed by the Devil; she is also possessed by contemporary patriarchal social, medical, technological, legal, and sexual controls.

Rosemary’s Baby tells the story of young newlyweds, Rosemary and Guy (John Cassavetes), who move into an apartment in New York where they befriend their seemingly harmless but overbearing neighbors, Minne (Ruth Gordon, who won an Oscar for her role) and Roman Castevet (Signey Blackmer). Rosemary quickly becomes pregnant, and the film then follows her painful, difficult, and confusing pregnancy. Despite the assurances from Guy, Minnie, Roman, and even her doctor, that her pregnancy is normal, Rosemary – and the audience – know that something is wrong. As her suspicion grows, in the film’s dénouement, Rosemary discovers that, in a pact reminiscent of Doctor Faustus, Guy promised his first born to a coven of witches, of which Minnie and Roman are part, in order to further his acting career. She discovers that she was raped by Satan, and has given birth to a Devil-child. The power of the film resides not only in its impressive combination of the naturalistic depiction of contemporary urban life with the surreal and fantastical depiction of the Satan-worshipping witches. It also resides in the way in which the film raises a number of complex questions: To what extent does a woman, pregnant or otherwise, “own” her body? To what extent can or should a woman’s (pregnant) body be subject to social concerns? Physically and socially, where is the divide between the mother’s body and the baby’s body? By raising these questions, Rosemary’s Baby is not only concerned with the spiritual but, also, the social possession of the female body.

The primary horror of Rosemary’s Baby lies not only in the creation and realization of an abject, grotesque, and demonic baby, but in the little control Rosemary has over her body and her pregnancy. After she discovers she’s pregnant, Minnie and Roman recommend a doctor who tells Rosemary not to read books, talk to friends about their experiences, or take vitamin pills. Instead, he recommends that Minnie makes her a daily drink. Discouraging Rosemary from gaining alternative opinions and pieces of advice from books and friends, and conspiring with Roman and Minnie to force Rosemary into consuming a strange drink, the doctor abuses his position of power; he controls Rosemary both physically and mentally. Even after Rosemary loses weight at the beginning of her pregnancy, complains of being in crippling pain for a number of months, and generally looks ill, the doctor assures her that this is perfectly normal. Betrayed, controlled, and manipulated by seemingly trustworthy people – her husband, elderly neighbors and doctors – Rosemary’s Baby plays on contemporary social, legal, technological, and medical anxieties regarding the “ownership” of the pregnant female body through this heightened and fantastical narrative about spiritual possession.

Released in 1968, Rosemary’s Baby reflects a time of change regarding the control over the reproductive female body. The Pill was approved for contraceptive use in 1960 giving women, at least in theory, greater control over their sex lives. The 1960s was an intense period regarding abortion laws in the States, eventually culminating in the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision Roe v. Wade. For A. Robin Hoffman, situating the film within its social and historical context is crucial as “we cannot understand what is horrifying about a horror movie without understanding the contemporaneous fears and concerns that penetrated both its production and the viewing public who first screened it.” Although Hoffman suggests that Rosemary’s Baby is a “social document of the growing horror of pregnancy…as reproductive technology and legal actions colluded to empower the fetus at the expense of the previously sacrosanct pregnant woman,” I relocate the horror of the film away from the visibility of the fetus and back onto the woman’s pregnant body. The horror, as played out in the narrative, is not primarily that the baby is a Devil-child, but that Rosemary has been coerced into carrying and then giving birth to this monstrous child. In this way, through the spiritual possession of Rosemary’s body, the film plays on the contemporary social anxieties surrounding the changing reproductive and sexual authority and autonomy women gained over their bodies due to the advances in medicine, technology and the law during this time.

However, the issue of bodily possession not only reflects the contemporary anxieties over a woman’s ownership of her body through pregnancy, but the assumption and investment in the pregnant body as a social issue. In the film, Rosemary’s body is subject to intense and constant scrutiny from other characters. She’s told she looks too chalky, too tired, too thin. Although these comments often stem from a place of genuine concern for Rosemary’s health, there’s an underlying assumption that the pregnant body is one on which we can freely comment. Indeed, at one point, as Rosemary’s (male) friend, Hitch, claims that “I was alarmed by her appearance”, Roman responds, “She has lost some weight, but that’s quite normal. Later she’ll gain, probably too much.” Roman’s response demonstrates the way in which the pregnant body, particularly with reference to weight, is constantly kept under surveillance. This is also true in our wider culture today. A regular feature in celebrity gossip magazines and newspapers, the “baby bump watch” observes the female celebrity’s weight gain (and then weight loss after the baby is born), maternity style, and diet and exercise regimes. As in the case of Kim Kardashian, the pregnant woman is viciously mocked and chastised if she does not fulfil the desired expectations. Likewise, among “normal” people, if a pregnant woman should choose to drink or smoke, she becomes the subject of disgust and disapproval due to the moralizing attitude society has towards her. Whilst there may be good health reasons not to drink and smoke (once again, we trust the doctors for this advice), it is the demand that women fulfill certain expectations, and the assumption that people have the authority to comment and criticize on another women’s body which is most worrying. Crucially, it demonstrates the extent to which a women’s autonomy over her body is limited. The child, the human race’s investment for its own continuation, and the embodiment of society’s futurity, becomes such a critical and crucial concern that the pregnant women’s body becomes a site of fleshy societal possession.

The final way in which Rosemary’s body becomes possessed is sexually. When Guy “sells” Rosemary to the witches, demonstrating his consideration of patriarchal entitlement over her body, Rosemary passes out after eating a drugged dessert made by Minnie, and is then raped by Satan in a bizarre, surreal, and extremely disturbing sequence. Later, after she’s awoken from this “dream” – the boundary between the imagined and the actual are indistinguishable at this point–, she finds scratches over her body, and Guy tells Rosemary that he “didn’t want to miss baby night”. In other words, he admits to marital rape. Although Rosemary seems a little upset and distressed at this, the film glosses over this fact. Given that marital rape, astoundingly, wasn’t made illegal in all 50 states until 1993, the film offers no position for Rosemary to be outraged at this violation. Her body, it seems, really does belong to her husband.

Famously and controversially, the sexual possession of the female body is not contained within the intertextual parameters of the film. In 1977, Roman Polanski, the film’s director, was arrested and charged with five offences against a 13-year-old girl, Samantha Gailey, including rape. Although he initially pled not guilty, Polanski later admitted to the charge of rape, but fled to France before he was sentenced. The United States authorities have failed to extradite him and, to this day, the charges remain pending. For some, particularly in the case of Woody Allen, the need to separate art from the artist is crucial. I remain skeptical over the auteur approach to filmmaking because, although film directors often have a pervasive vision and the overall authority when making creative decisions, it also neglects the contribution made by other departments including producers, screenwriters, and cinematographers. In this way, I do not read Rosemary’s Baby as wholly Polanski’s vision. Nevertheless, the crimes of which he has been accused are abhorrent, and a discussion of the possession of the female body, particularly the sexual possession of Rosemary’s body, must be read in light of these crimes. For me, on a personal level (for I do not wish to speak on behalf of women who have experienced sexual abuse and may perceive and react to the film differently), these crimes lessen the impact of the moments of resistance in the film. At one point, at the beginning of her pregnancy, Rosemary gets a haircut, suggesting her desire to reclaim her body, even in a small way. Similarly, at another point in the film when Rosemary, looking particularly ill, throws a party, a group of her female friends rally around her and encourage her to seek a second opinion due to her current doctor’s failure to acknowledge her difficulties with the pregnancy. Crucially, they shut Guy out of their conversation, claiming it’s for “girls only”. This moment, whilst in other circumstances, may powerfully demonstrate the way in which women, as a communal force, are able to undermine patriarchal dominance, for me feels hollow. Infiltrating the way in which I read the film’s inter-textual moments of the resistance, the extra-textual events forcefully undermine the moments of power and autonomy offered to these women.

Through the fantastical spiritual possession narrative, Rosemary’s Baby powerfully and effectively reveals the contemporary social, medical, legal, technological and even, to an extent, sexual anxieties surrounding the possession of women bodies which remain relevant and pervasive today. However, although the film reveals these anxieties, it fails to resist them, and even, through the acts of the director, becomes complicit in them. Nevertheless, by continually challenging the way in which the female body – pregnant or otherwise – is considered to be “owned” by outside patriarchal forces, we can anticipate a future where the female body is unanimously her own. In other words, we can anticipate a future where the female body is neither spiritually nor socially possessed.

__________________________________________________

Sarah Smyth is a staff writer at Bitch Flicks who recently finished a Master’s Degree in Critical Theory with an emphasis on gender and film at the University of Sussex, UK. Her dissertation examined the abject male body in cinema, particularly focusing on the spatiality of the anus (yes, really). She’s based now in London, UK and you can follow her on Twitter at @sarahsmyth91.