|

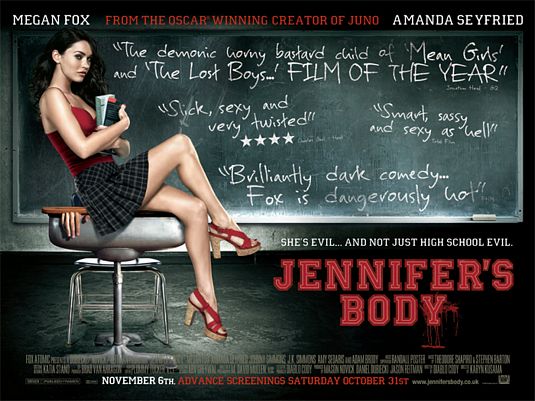

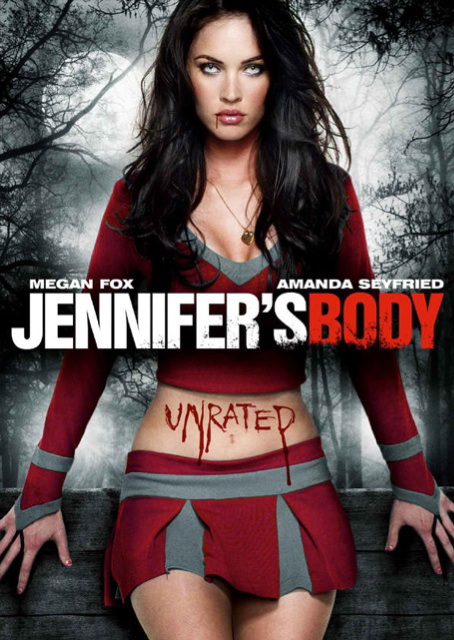

| Jennifer’s Body (2009) |

Jennifer’s Body, the 2009 horror chick-flick that was a coming-of-age for sex goddess Megan Fox after hyper-lucrative, career-building toil under the aegis of Michael Bay’s teenage-boy-centric Transformers franchise, now enjoys a cult following outside the Transformers demographic. And yet, on release, Jennifer’s Body was widely panned by reviewers who were oddly outraged by its unworthiness. (Maybe they were bought off, but that would be another story.)

Maybe the male critics and audience somehow sensed this was the break-up film. Simultaneous to its release, Fox untied her tongue in interviews, famously comparing the Transformers director to Hitler, a salvo that sealed her fate with the franchise and, at least initially, its fans. They felt betrayed.

|

| Megan Fox as Jennifer |

They were right, they had been betrayed: by their own phallocentric delusion that women exist to serve men, and its tributary delusion that Megan Fox enjoyed performing the objectified sidekick to Shia LeBoeuf’s action hero, and more poignantly, that she intuited from the far side of the screen how hot she made them, each guy individually, and that meant something to her beyond a sense of power and a pay check. She was their admission-priced, inaccessible, fantasy, group girlfriend. Until she wasn’t any more. Sorry, Boys. Game over.

It took chutzpah to give Bay that well-publicized kiss-off. The same year Jennifer’s Body, directed by Karyn Kusama, grossed $30 million worldwide on a $15 million budget and uniformly dismal reviews, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, directed by Michael Bay, grossed $400 million on a $200 million budget. (But that’s yet another story.)

SPOILER ALERT: Out of respect to writer Diablo Cody’s wondrous storyline, I’m not pretending this movie is only worth seeing once and in total ignorance. In fact, it must be seen at least twice to be fully appreciated. Call it complex storytelling, hidden depth, flaws in the plot structure and/or direction, or all of the above.

Jennifer’s Body is the story of a lush cheerleader ritualistically murdered by the cute lead singer of boy band Low Shoulder, in a pact with the Devil for fame and stardom. Unfortunately for the teenage males of suburban Devil’s Kettle, the cheerleader is thereby transformed into a bite’em’n’eat’em serial killer, selecting, seducing, and isolating male classmates before offing them at their most pathetically tumescent — on the brink, they think, of experiencing the private pleasures of her flesh. Bummer for the guys onscreen and a refreshing, amusing twist for a jaded female audience.

|

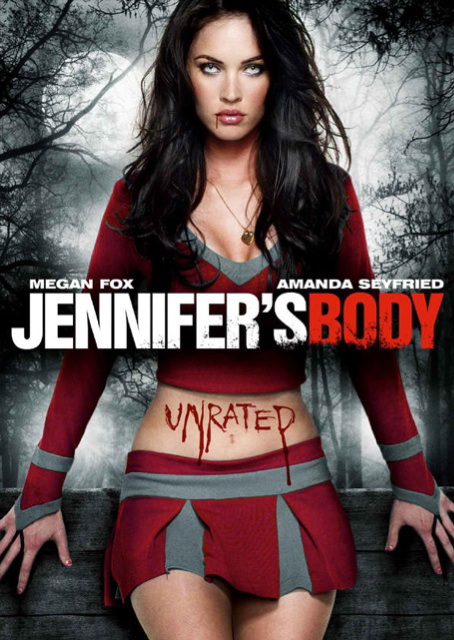

| Needy (Amanda Seyfried) and Jennifer (Megan Fox) |

Demon-Jennifer is a bodacious avatar of female rage — plus other less righteous emotions, hormones, and vanities. Her story is told by best friend Anita, nicknamed Needy, the gawky sidekick in glasses who’s a bit smitten by Jennifer’s “saltiness.” Needy eventually figures out her friend is “actually evil.” For her boyfriend Chip’s sake, Needy is forced to fight her to the death. As narrator, Needy frames the action, told in flashback, from her prison cell. This formal device complicates the plot but pays off in a clever denouement shown in a montage of stills and video under the closing credits. As I write that sentence, I have to wonder why this vital piece of story — Needy’s revenge massacre of Low Shoulder — is relegated to an afterthought.

So, it’s a (media) story within a (movie) story, a star within a character, and a film within a genre or two. Any way you slice it, Jennifer’s Body is disputed territory — which gives that awkward title the post-modern cachet of multiple readings. Is it slasher? Chick flick? Coming-of-age? Vampire? Feminist? Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. It’s even vampire-lesbian, a tease it declines to exploit; teen psycho, cultural satire, and New Romantic.

|

| Amanda Seyfried as Needy |

Two things make the film hard to watch, or clearly “see.” First, Megan Fox’s bravura glamour. As Needy, Amanda Seyfried is every inch an actress and holds her own, but Kusama’s camera gives Fox’s fearsome symmetry the kind of attention ultimately detrimental to a storyline. No one’s going to complain, but droolworthy Fox detracts from Needy’s story, and that’s a problem because Needy is our low-profile protagonist, and she bookends the film. For the script to work, we have to root for both halves of this dynamic duo, until we let go of Jennifer and follow Needy, whose rage is less psychosis and more personal-is-political focus.

Second, Diablo Cody’s free-form plotting, with its gratuitous flashbacks and ill-timed exposition, impedes the film’s forward drive. The most glaring example comes three-quarters in, when Jennifer suddenly decides to let Needy and the audience in on the details of her own heinous murder. We don’t know why we’re suddenly watching a missing narrative chunk in flashback, but the footage is compelling and when it’s over, Jennifer suddenly comes on to Needy in their much hyped lesbian moment. Heat trumps logic, just like in high school. Are they going to do it? No. Was it actual lesbian heat? Um. Can hormonally unstable Jennifer’s power plays be assigned a stable orientation other than “on?”

|

| Demon Jennifer |

Since Jennifer herself is clueless how she returned from the dead, Needy makes a trip to the Occult section of the campus library to discover “demonic transference happens when you try to sacrifice a virgin to Satan who isn’t an actual virgin.” Great. Now Needy’s best friends with a demon. She tries to warn Chip, who, as her boyfriend, is the obvious next victim on Jennifer’s list of perversions.

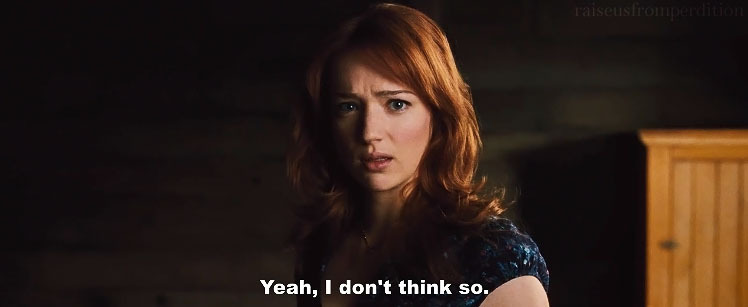

Needy: Jennifer’s evil.

Chip: I know.

Needy: No, I mean, she’s actually evil. Not high-school evil.

Such stock-in-trade dialogue wherein the danger to an individual or the community is willfully ignored, is kept to a minimum, yet it’s one of the treats of the monster genre. Remember the original Dracula (1931), with Bela Lugosi? It’s worth a look, in sumptuous black and white. Yes, it’s ham-fisted, stilted, stagey, featuring a bat on a string, but it’s pretty authoritative about Transylvanian vampire lore — sleeping habits (coffin, native soil, diurnal), telltale signs (no reflection in mirrors, fear of sunlight), and remedies (garlic, crosses, stake through heart). Tracking and dissecting vampire quirks is half the fun of having them around.

|

| Vampire trope |

The pleasure of recognition, that ghastly chill down the spine, is mostly missing here, because this is less a genre movie than a rite of passage dressed-up in the tropes of horror. Emotion, intuition, everyday telepathy between close friends are on a sliding-scale from everyday reality to full-blown inexplicable mayhem. Rules governing demons are introduced piecemeal, and Jennifer’s sudden new talents — like projectile vomiting black goo — are momentary gross-outs devoid of gravitas. Such tricks work less well a second time. Worse, Jennifer’s ability to rise in the air and hover is abruptly revealed in the climactic fight scene to no strategic advantage. Surprising but not really satisfying, the hovering trick later powers Needy’s prison escape. Is that why it was introduced when it wasn’t necessary?

So, okay, Cody’s script is loose-weave. It’s also fresh, grrrl-centric, fed-up with male ego/privilege, and full of satiric touches. And yeah, Megan Fox overwhelms the cast and crew with her performative beauty, but she’s both a great icon for most-popular-cheerleader-with-perfect-cheekbones and a recognizable teenager: a bipolar wreck under her foundation, an insecure bitch seducing her best friend’s boyfriend, a naive groupie seeking validation from a small-time boy band “from the city.”

The central pleasure of Jennifer’s Body — the confusing love Needy feels for Jennifer, and the trouble she takes to clarify that feeling, and act on it (revenging Chip), then act on it again (revenging pre-demon Jennifer) — might be precisely what turned off male reviewers. For all the promise of eye candy going in, this is a story about young women negotiating the horrors of the adolescent-to-adult obstacle course with some dignity, loyalty, and social conscience intact. The infamous male gaze has to work harder to appropriate a film told from the p.o.v. of cute but bookish, shy but self-respecting Needy, whose closest bond is, and might ever be, her friend Jennifer.

The two girls have four big scenes together:

Date with Destiny: Jennifer uses Needy as a disposable date in her quest for the Low Shoulder lead singer, to the annoyance of Chip, who had a date with his girlfriend. When bad things start to happen at the rustic Melody Lane Tavern, Jennifer ignores Needy’s screams to leave. Oblivious to danger or perhaps unconsciously courting self-destruction, Jennifer gets into the band’s scuzzy retro van. Cue: loss of innocence.

|

| Jennifer and Needy’s much-hyped lesbian moment |

Same-Sex practicum: Jennifer hides in Needy’s bed, confesses her own murder, then starts making love to Needy, who lets herself go until she jumps off the bed screeching, “What are you doing?” By scene’s end, Needy knows she has to be the adult.

Prom Night from Hell: in a swampy, abandoned public pool, Jennifer kills Chip and fends off a tongue-lashing from Needy before slithering away without eating his flesh. This climactic scene is less exciting than it should be, crushed under the weight of an overly elaborate set and Jennifer’s ho-hum hovering, but signals the beginning of the end.

Liebestod: Jennifer’s bedroom, when Needy comes in through the window to kill her. In this passionate encounter, the two young women fight like wildcats on the bed and in the air. The fight is physical, metaphysical, and deeply emotional. When Needy rips the BFF locket from around her neck, Jennifer’s eyes register defeat, loss, submission. If she’s not Needy’s best friend forever, what’s the point of immortality? With suddenly slack lids, she gazes into Needy’s eyes in eroticized surrender. How do you spell Romantic death wish? Finally, Needy has topped Jennifer. Maybe that’s all she ever wanted. Then comes the death blow: box cutter to the heart. Wow.

Online movie review clearinghouse Rotten Tomatoes gives Jennifer’s Body a measly 43% rating, which I take as an indication of factors, like misogyny and male entitlement, beyond the reach of wonderful filmmaking. Their summary judgment: Jennifer’s Body features occasionally clever dialogue but the horror/comic premise fails to be either funny or scary enough to satisfy. I guess it all depends on who you’re trying to “satisfy.”

———-

Erin Blackwell is a practicing astrologer who blogs at venus11house and pinkrush. Congratulations to Megan Fox and Brian Austin Green on their new baby boy.

The refrains go something like this: the books are poorly written and riddled with cliches, the people who like them must be dupes of the patriarchy or simply burdened with bad taste. These screeds overlook what makes the series compelling for millions of women and girls. In my time with Twilight fans around the world—from the occasional forum participant and those who watched the films fifty times to the person who corralled her entire office into choosing Team Edward or Team Jacob—I have found they also spoke of how the fanpire transformed their everyday lives, not as mere escapism but as a vehicle for connecting with others and forging new identities beyond that of Mormon mother or ordinary teen.

The refrains go something like this: the books are poorly written and riddled with cliches, the people who like them must be dupes of the patriarchy or simply burdened with bad taste. These screeds overlook what makes the series compelling for millions of women and girls. In my time with Twilight fans around the world—from the occasional forum participant and those who watched the films fifty times to the person who corralled her entire office into choosing Team Edward or Team Jacob—I have found they also spoke of how the fanpire transformed their everyday lives, not as mere escapism but as a vehicle for connecting with others and forging new identities beyond that of Mormon mother or ordinary teen.