This post by Ren Jender appears as part of our theme week on Movie Soundtracks.

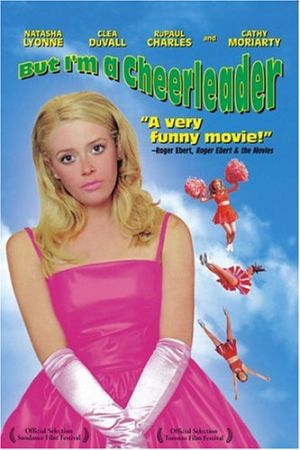

When I listened to post-punk and New Wave bands as a teenager in the ’80s I never dreamed that members of some of those bands would someday write the scores for successful, mainstream films: Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo composed the music for many movies including Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums. Danny Elfman of Oingo Boingo is the composer for Edward Scissorhands, Good Will Hunting and more. These two men followed a path that Randy Newman–who was a great, satirical songwriter before he became the composer for films like Toy Story–and Henry Mancini, composer of the score for Breakfast at Tiffany’s and The Pink Panther, tread before them. This pipeline has not, historically, been open to women musicians, even though Kate Bush, for example, was popular at the same time Devo and Oingo Boingo were, and during that time put out music that could already pass for the soundtrack to a movie. Although Karen O of The Yeah, Yeah, Yeahs was nominated for an Oscar this year for her work on the movie Her, she also, at one time, dated the film’s director which shouldn’t be a prerequisite for a woman (or anyone else) getting the job.

Lisa Gerrard of Dead Can Dance, one of the few successful women musicians who made the transition to film composer (she won a Golden Globe for her work on Gladiator), wrote and performed the music for 2002’s Whale Rider–-and she didn’t have to date writer-director Niki Caro to do so. Gerrard might seem an unlikely choice: when I briefly worked in a women’s sex shop in the 90s, the store owner told me not to play Dead Can Dance on the sound system because they scared away customers. But Gerrard’s score for Rider does what the best movie music is supposed to do: reinforcing the drama of the film without calling unnecessary attention to itself.

Whale Rider is an adaptation of the book of the same name by Māori author Witi Ihimaera about an 11-year-old girl (played by Keisha Castle-Hughes with the same confidence and solemnity Quvenzhané Wallis brought to Beasts of The Southern Wild; both girls received well-deserved Oscar nominations) who believes she is destined to become chief of the Māori living in the small community of Whangara, New Zealand, and her conflict with her grandfather, the aging chief, who believes only men can lead.

Pai’s grandfather (Rawiri Paratene) is often cold toward her, seeming to blame her for the death of her twin brother at birth, whom he believed was destined to be the community’s leader. Pai says, “(He) wished in his heart that I’d never been born, but he changed his mind.” In spite of himself, the grandfather sometimes shows great affection for and great pride in his granddaughter, letting her ride with him on his bicycle and telling her the legend about an ancestor (for whom Pai is named) migrating to New Zealand on top of a whale.

Although sexism seems entrenched in their traditions (as they are in so many Western ones) the Māori women (played, as all of the nonwhite characters are, by people who are actually Māori) in the film are hardly doormats. When the grandfather is so upset at the loss of his newborn grandson that he barely acknowledges his granddaughter, the grandmother (Vicky Haughton) ignores her husband and coos to the baby girl, “Just say the word and I’ll get a divorce.”

The grandmother’s friends aren’t above teasing and laughing at Pai and are bawdy when they talk to each other. When Pai tells these older women to stop smoking because it will interfere with their reproductive capabilities, the women raise their eyebrows and after she leaves, one retorts, “You’d have to be smoking in a pretty funny place to wreck your childbearing properties.”

Pai is given the chance to stay with her father, a successful artist in Germany, who says of his father (the grandfather) and his hopes that a young male leader will rid the community of the poverty and malaise we see, including casual drug and alcohol abuse, “He’s just looking for something that doesn’t exist anymore.”

Pai agrees to go live with her father, and the shiny, new SUV they ride in as they leave the grandfather’s modest house is a world away from the bicycle the grandfather uses to get around. But when they pass the ocean we hear Gerrard’s distinctive vocals, akin both to whale “singing” and to the traditional Māori chants we hear in the film. Pai, feeling like the whales are calling to her, opts to stay.

While her grandfather starts to train the ragtag group of “first-born sons” in the ancient ways. Pai, with encouragement from her grandmother and some coaching from her uncle, masters songs, dances and weapon training–without letting her grandfather know she is doing so–too. The grandfather throws his carved whale tooth pendant into the ocean from his boat and waits for one of the boys who accompany him to bring it back, but he takes to his bed when none of the boys can pass this final “sword in the stone” test. Pai, later on a boat with her uncle, his drinking buddies and girlfriend, dives to the bottom and retrieves both the pendant and a lobster at the same time.

Gerrard’s ethereal vocal style combined with electronic flourishes make for an unusual soundtrack, but one that meshes with the film’s bracing mixture of mysticism and realism set against the strange and beautiful New Zealand landscape with its high grey cliffs and bright green hills (which audiences might recognize from The Lord of the Rings movies) better than a more traditional soundtrack from John Williams (or Randy Newman) would. When Pai pushes her forehead into the skin of a beached whale, then climbs the clusters of barnacles on its side to steer the animal into the water, the sound of the waves melds with the music and we feel like we are taking off with her.

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtZC5OOxoAQ”]

___________________________________________________

Ren Jender is a queer writer-performer/producer putting a film together. Her writing. besides appearing every week on Bitch Flicks, has also been published in The Toast, RH Reality Check, xoJane and the Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @renjender.