This is a guest post by Elle Schneider.

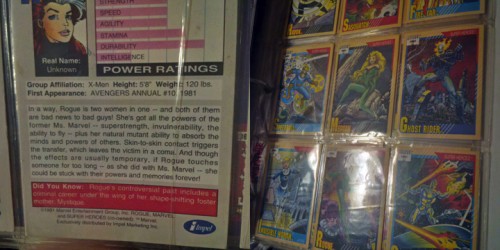

Blade Runner has been my favorite film since a sleepover in sixth grade, and I have 200 Star Wars figures and thousands of Marvel cards stashed away in in my childhood closet (in protective cases, obviously, what kind of barbarian do you take me for?).

It was Wes Craven’s Nightmare on Elm Street that made me realize I could make a film by splattering blood on some friends, and James Bond became my directing aspiration. And as far as I knew, this made me just like any other girl growing up in the 80s and 90s.

Nothing has made me more appreciative of my upbringing than the Verizon spot that’s gone viral in the past few weeks, about all the little micro-aggressions that bully women into a societally accepted mold, away from the common interests that all kids share like building and dinosaurs. The spot made me wonder about other ways this belittling behavior has affected women, especially in the way it affects the kind of films women want to watch—and make.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/XP3cyRRAfX0″]

What if you grew up hearing, “Isn’t this movie a little too scary for girls?”

We worry rightly about girls having heroes to look up to and there is an undeniable need for gender parity in onscreen protagonists. But why must we designate girl heroes for girls, and boy heroes for boys? What’s wrong with a character like Indiana Jones being a hero for both boys and girls? Because it teaches girls to be adventurous? And why, as an industry, are we so massively afraid of letting a woman make a film like Raiders of the Lost Ark?

We tell boys that they should tell any story they want—whether it’s their own struggle or Indiana Jones’ struggle. We laud men who adapt Austen, or make a great biopic about a female heroine like Hawaiian Princess Ka’iulani, as my friend Marc Forby fought for nearly ten years to do. At Cannes 2012, when no women appeared in Competition, filmmakers like Michael Haneke and Jacques Audiard were praised for making great films about “powerful” female characters. The question was raised: does it really matter how many women are represented as directors so long as stories about women are being told?

Sharon Waxman of The Wrap held court at a panel at the American Pavilion that year to discuss the issue of gender at Cannes, and I raised my own question: how can we help the women who want to work in genre films? Her response was one I’ve often heard from women disinterested in genre: “Women shouldn’t feel like they have to make the movies that men make.”

But what if that’s what I want to make? And why is that a bad thing? What if I want to make the same kind of film that excited me as a child, just like Gareth Edwards, Ryan Coogler, Rian Johnson, or any other male filmmaker has had the opportunity to do?

When women filmmakers get that rare chance to make a film, we’re usually encouraged to use the opportunity to focus on a “woman’s story” with a “strong female protagonist,” as if a female filmmaker’s first duty is to social issues rather than storytelling or forging a career. But what the hell is a woman’s story, anyway?

Try as society might, women are not one homogenous group; women are not a hive-minded audience solely interested in stories that reflect a single shared experience. Ticket sales show that women make up 50 percent of the theatrical box office, despite the low number of female protagonists on screen, and that’s because women are not myopic viewers. On the contrary, women see men and women as people; men see men as people and women as women. Unlike male viewers, a woman’s story really could be anybody’s story, if only we were encouraged to tell anybody’s story.

I recently had a conversation with a group of women filmmakers who were insistent that men and women are just different kinds of storytellers—women are just naturally more “grounded” and “realistic” in their characters and settings, and that’s why women can’t get work in the testosterone-driven studio system. Studio films are male-power fantasies anyway; one participant mentioned that average white guys are constantly writing action movies, imaging themselves as Ethan Hunt, when they look nothing like Ethan Hunt. Women don’t project fantasies like that; we write what’s real.

Except that’s not true. As the National Science Foundation study cited in the Verizon spot, 66 percent of fourth grade girls express an interest in science. Many young girls I knew growing up were writing amateur versions of Lord of the Rings, as George Lucas and James Cameron did on their path to making Star Wars and Avatar. These were personal fantasies, stories where we played out our day-to-day dramas, angst, and adolescent ideas about the world through the avatars of fictional characters and settings. As a 12-year-old, this was natural. But as a 28-eight year-old? Why bother writing what you know you can’t afford?

As Lexi Alexander succinctly put it: “What do we say to a 12-year-old girl who watches Star Trek for the first time and says: ‘I want to make movies like that.’ Do we say: ‘Yeah, try to reduce your vision to something that’s crowdfundable, you’re a girl after all’?”

The reality is we do say that, as a society, if not in so many words. Women’s stories do tend to be “small” and “personal” because we’re taught to pare down from the get go, to trim our own wings before we can fly. Women are taught to expect limited resources, to envision the world through the scope of our often purposely sheltered life experience. Women are not taught to ask for more, and worse, are not taught that asking is even an option. Women’s stories are the stories of those without a voice.

It’s a myth that women are inherently unable to envision or execute large scope or genre-driven projects, a myth that too many women buy into themselves. That myth is what keeps women from being studio contenders, as Indiewire blog The Playlist recently illustrated in their article “10 Indie Directors Who Might Be The Next Generation Of Blockbuster Filmmakers.” The article features 10 eligible white, male heirs to the throne of Hollywood—because the (male) writers at Playlist can’t envision even someone as accomplished as Debra Granik—whose Winter’s Bone launched the career of blockbuster and Reddit darling Jennifer Lawrence, and whose Vietnam vet doc Stray Dog just won the LA Film Festival—successfully helming a big-budget feature.

Granik has more than proved her chops as a storyteller, and she’s done it by with compelling, award-winning portraits about strong men and women. Brit Marling, Lexi Alexander, and countless others have done the same. When do we get to see their takes on Star Wars, whose best installment was written by a woman, Leigh Bracket, back in in 1979? That’s the kind of woman’s story I want to see.

Elle Schneider is a writer and director of the genre persuasion. Award-winning graduate of USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, she was the cinematographer of SXSW Film Festival selections I AM DIVINE and THAT GUY DICK MILLER, and is a co-developer of the Digital Bolex cinema camera. She is raising production funds for her action comedy HEADSHOTS this month on Seed&Spark. You can find her on the twitters @elleschneider, and she is deeply sorry to have exceeded 1,000 words.