|

| Arrested Development promo. |

When

Arrested Development first aired in 2003, the news cycle was heavy with stories of Enron-like corporate scandals and the escalating Iraq War. The first run of the series–from 2003 to 2006–relied heavily on inspiration from news stories about crooked corporations and wartime scandals to draw the Bluth family and their

“riches-to-rags” story.

After a seven-year hiatus, during which rabid fans hoped, speculated and begged for more, the fourth season of Arrested Development debuted on Netflix on May 26, 2013.

During the hiatus, America has dealt with the housing bubble and economic collapse, high unemployment, sweeping legislation against reproductive rights and a

lot of hand-wringing over the

“Mancession” and the supposed

“end of men” in American culture. There is plenty of comedy fodder buried in the depths of societal despair, and Mitch Hurwitz and company took full advantage.

In the first three seasons of the show, Michael Bluth was our good guy–the ethical, self-aware, hardworking man in a sea of familial dysfunction.

|

| Michael considers his failings while a vulture watches on. |

In the first episode of season 4, however, we first see Michael drunkenly ascend the stairs of the stair car (now emblazoned with the “Austero Bluth Company” logo) to try to settle a debt with Lucille 2. Sally Sitwell makes a snide comment about how she’s glad she didn’t marry him, and Michael attempts to seduce Lucille 2 for the money.

Michael is not the golden son we knew before. And while everyone in the Bluth family is, on some level, remarkably terrible, Michael’s fall from grace is especially jarring–and it’s supposed to be.

|

| Lucille 2 is not interested in Michael’s desperate advances. |

He’s living in George Michael’s dorm room and taking classes through the University of Phoenix. He’s clueless and desperate, lost after the housing market crashed and he loses control of his company. He tries to construct a new subdivision, but it doesn’t have the proper utilities. He can’t quite get anything right.

Arrested Development‘s new season is a comical, satirical look at the idea of the Mancession and the threat to traditional American masculine identity that writers and pundits have been analyzing and panicking about for the last few years. Jobs that have typically been held by men–construction and manufacturing, as well as finance–disappeared during the recession. Michael’s fall from grace echoes the fall from dominance that men in his position seem to have suffered during the recession.

The patriarch of the family, George Sr., is also a “victim” of emasculation in this season. Living in a commune-turned-corporate retreat with Oscar, a 21st century Roger Sterling and his female companions, George Sr. partakes in maca root that is downhill from a porta-potty. (A reddit commenter

noted that the maca was probably affected by women who were on birth control pills using the toilet, which is a common

anti-birth-control battle cry.) George Sr. is indeed feminized by his drug use, and a doctor confirms that he has the estrogen levels of a normal, healthy woman, and that he has almost no testosterone. He cries, feels weak, complains that he hates the way he looks and worries about looking fat (Lucille 2 responds by calling him a “drama queen”).

|

| Her? |

George Sr.’s continuous fall from power into obscurity is shown by his becoming more and more like a woman. While on another show this might be unbelievably offensive, it works on Arrested Development because we are laughing at the characters, and their dysfunction is highlighted by sexist remarks, cultural appropriation and casual racism.

Perhaps most noteworthy about Michael and George Sr.’s descents is that the two men have little to no control over what’s happening to them or around them. A hallmark of the recession’s effect on men, and the proceeding news that women are increasingly breadwinners and are out-pacing men in college and rising in the ranks in the workforce is just that: a desperate feeling of a lack of control. This is why pundits on

Fox News engage in “man-panic” and try to say that science shows men are superior. This is why bloggers list all of the ways the

“American man” is threatened by the changing economy.

The other men are involved in sub-plots dealing with masculinity and homosexuality. George Michael (who hates his name and tries to disconnect himself from his father) studies in Spain, growing a mustache and having an affair with a Spanish woman who he works as a nanny for. Gob’s episode is a spoof on the masculine-fueled

Entourage, and he struggles with aging out of the youthful party scene. Gob and Tony Wonder, trying to enact revenge upon each other, fall in friendly love and blur the lines between friendship and romance. When George Michael says that his name is “George Maharis,” he chose the name of an

actor who in 1974 was arrested for having sex with a male hairdresser named Perfecto Telles (the name of Maeby’s under-aged boyfriend).

For a brand of men for whom being emasculated is pretty terrifying, they are subjected to a great deal of it in season 4.

Buster, who grows from a “mother boy” to a “mother man,” has an affair with the wife of a politician (Herbert Love, a black Tea Party-inspired politician who is strongly against birth control coverage). He re-joins the Army and becomes a drone pilot, thinking he’s getting unlimited juice boxes and playing video games. His inability to kill a kitten, however, gets him discharged.

Arrested Development manages to parody everything–even drone strikes–and make it work.

|

| Tony Wonder plays gay for his act, but he and Gob share an intimate relationship that evolves into a game of sexual chicken. Speaking of chickens, here’s a National Geographic post that analyzes the Bluths’ chicken dances. Amazing. |

Hannah Rosin turned her

Atlantic piece,

“The End of Men,” into the book,

The End of Men: And the Rise of Women. She examines the changing roles of men in society, and how women are taking charge at home and at work.The women of

Arrested Development often have a sense of agency and control that women don’t always have in comedic sitcoms. Lady T, who looked at the main female characters through a feminist lens in her piece for

Bitch Flicks, says,

“The Bluth-Funke women make up some of the most entertaining, well-rounded characters on television. They provide just as much laughs as the male characters on Arrested Development and help to dispel the ridiculous claims that ‘women aren’t funny.'”

Lucille (1 and 2), Lindsay, Maeby and even Ann are powerful figures in season 4 and figure prominently in plot lines involving the leading men. I think it’s safe to say that compared to the male characters, we feel less sympathy for the women, because they are, on the whole, less pitiful.

|

| Lucille on The Real Asian Prison Housewives of the Orange County White Collar Prison System. |

Lucille Bluth and Lindsay are both shallow and conniving as ever. Lindsay’s spiritual journey is laughable (“I read some of Eat, Pray, Love,” she says), but she does what she wants, just like Lucille, who manages to infiltrate a gang of Asian women in prison. In flashbacks, Kristen Wiig is amazing as a young Lucille.

|

|

“I’m surrounded by squalor and death and I still can’t be happy.”

|

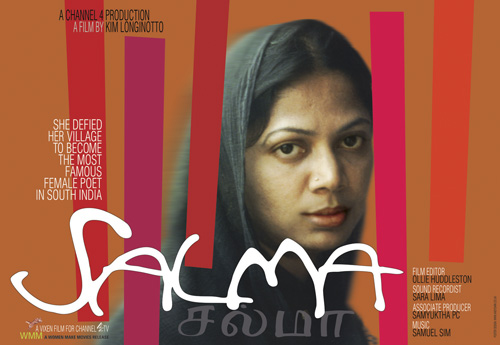

Lucille Austero is running for office against Herbert Love, and has a powerful corporate position.

Maeby, attempting to finish high school and feeling insecure about the fact that she hasn’t and the fact that her career in film production is ending, pimps out her mother and runs an aggressive PR campaign for George Michael’s fake FakeBlock.

|

| Maeby’s film career gets cut short, so she gets creative. |

Ann had a child with Tony Wonder and is planning on marrying Gob, but he backs out, and she manages to get back at both of them.

In short, the women of Arrested Development continue to have a great deal of twisted power, just as they did in previous seasons.

George Michael and his father have been dating the same woman, Rebel, and the two come to blows at the end of the season. George Michael rejects his name and punches his father, and enters himself into the canon of men with daddy issues in film and media, including his own father and grandfather.

This third generation of Bluths–George Michael and Maeby–are products of the arrested development of their family and are fulfilling the roles that have been laid out for them, even as they try to rebel.

The way that Arrested Development tackles–no, skewers–current issues and societal woes makes it brilliant and surprisingly timeless. From corporate fraud to war scandals to economic crashes to gender norms, the same issues and problems arise time and time again. Society is, indeed, one big roofie circle.

|

| You can catch Tobias on the evangelical television network. |

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.