|

| Willow Rosenberg (Alyson Hanigan) on Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

Written by Lady T.

Joss Whedon is known for creating and writing about strong female characters in his science fiction shows. One of the most popular and complex of these characters is Willow Rosenberg from

Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Willow speaks to many people and quite a few have named her their favorite character on the show, from Mark at

Mark Watches to Joss Whedon himself, who put the most Willow-centric episode of the series (“Doppelgangland”) on

his list of favorite episodes.

Another thing that makes Willow so appealing is the fact that her character arc over seven seasons can’t be described in only one way. Some see Willow’s story as a shy, brainy computer geek embracing her supernatural power in becoming a witch.Others relate to her arc as one of a repressed wallflower who explores her sexuality and finds more confidence in coming out as a lesbian. Still others are fascinated with the different ways she handles magic, and her recovery after drifting too far to the dark side.

What story is told when those three arcs are put together? For me, the story of Willow Rosenberg is the story of a woman who spends years defining and re-defining herself, rejecting roles that other people have chosen for her – for better and for worse.

From the very first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Willow has been presented as a shy, sweet, helpful friend to the titular heroine– and from the very second episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Willow has shown herself not to be as sweet or innocent as everyone thinks she is. When she meets Buffy for the first time, she’s eager and friendly, bubbling over with information, in awe that this mysterious, cool new girl is talking to her, but also wanting to help in any way she can.

|

| Willow (Alyson Hannigan) talks to Buffy (Sarah Michelle Gellar) |

This eager beaver persona is the one that Willow adopts for most of seasons one and two.She becomes the Hermione to Buffy’s Harry, using her computer hacking skills to assist whenever Buffy needs more research for demon-fighting and she can’t find the answers in one of Giles’s books. And for these two years, Willow is notonly content in this role, but she thrives in it. Like her best friend Xander (my favorite character on Buffy), she’s found a place where she belongs. She’s found a purpose in fighting the good fight against the forces of evil, and she doesn’t seem to mind that she’s a second banana to Buffy. As long as she can put her skills to use and she’s fighting the bad guys, she’s happy.

This changes when Willow discovers magic.

Near the end of season two, Willow begins exploring supernatural arts. She doesn’t do much beyond research and reading, but despite her lack of practice, she thinks that she has what it takes to perform a spell that will restore Angel’s soul.

Watching the season two finale with the perspective of hindsight is more than a little uncomfortable, because we know how much Giles turns out to be right when he tells Willow, “Challenging such potent magics through yourself…it could open a door that you might not be able to close.” It’s also uncomfortable because we can see that Willow is more interested in proving her skills in magic than doing the right thing. She wants to help Buffy, obviously, but she also wants to prove to everyone – and to herself – that she can do the spell.

And she does.

|

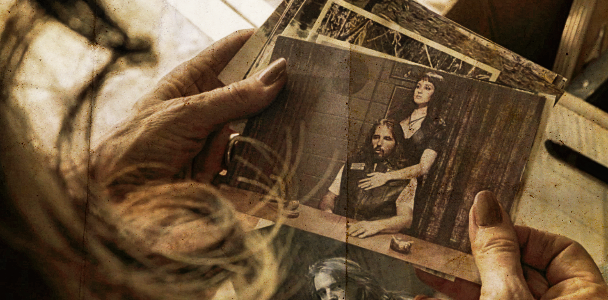

| Willow possessed as she performs the spell |

Angel’s spell is restored several minutes too late, and Buffy has to kill him anyway. But Willow doesn’t think about this potential consequence. She excitedly tells her friends, “I think the spell worked. I felt something go through me.”

After that,Willow becomes less meek, less shy, and more risky with her use of magic. She tries to use magic to make her and Xander fall out of lust with each other (in a plotline that I hate and always will hate, by the way), and is angry with him when he confronts her for resorting to spells. She becomes even angrier in season four when she, Oz,Buffy, and Xander are trapped in a haunted house and Buffy criticizes her aptitude in magic, saying that Willow’s spells have a 50% success rate. Willow responds with a flustered, “Oh yeah? Well – so’s your face!” but then follows up with a bitter, “I’m not your sidekick!”

Shortly afterwards, Willow tries to perform a spell that winds up failing. This is in an episode entitled “Fear, Itself,” where each major character confronts his/her major fear. Oz is afraid of the werewolf inside him, Xander is afraid of being invisible to his friends, Buffy is afraid of abandonment, and Willow…seems to be afraid of her spell going wrong?

|

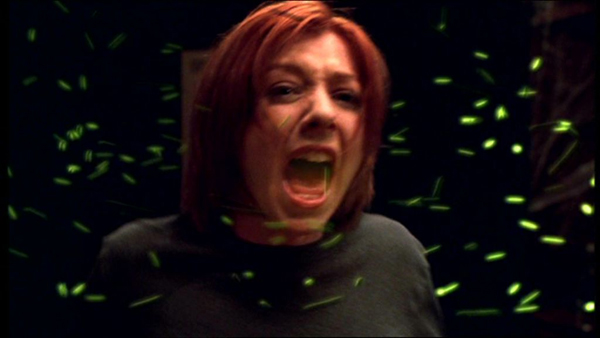

| Willow’s spell goes wrong |

Compared to her friends’ worries, Willow’s fear seems a little superficial. At the end of the season, though, we learn that Willow’s fears are about much more than simple experiments going wrong.

By the end of season four, Willow has gone through a few pretty significant changes. She’s become more focused on magic and less focused on her scientific, “nerdy”pursuits. She’s farther apart from Buffy and Xander than ever, despite loving both of them. She’s entered a romantic relationship with a woman. Most significantly of all, Willow is confident. She has a life that is fully her own, where she has two things (Tara and magic) that are hers. She’s entered a new phase in her life.

Or has she? After watching Willow’s dream in “Restless,” we can’t say that this new Willow is any more confident or self-assured than the old one who couldn’t stand up for herself when Cordelia Chase insulted her by the water fountain.

Joss Whedon’s writing for Willow’s dream is clever and filled with misdirection. Characters talk about Willow and her “secret,” a secret that she only seems comfortable discussing with Tara. Dream-Buffy constantly comments on Willow’s “costume,”telling her to change out of it because “everyone already knows.” We’re led to believe that Willow is afraid that her friends will judge her for being gay and being a relationship with another woman…but this isn’t the case at all.

Instead, when Dream-Buffy rips off Willow’s costume, we see a version of Willow that is eerily reminiscent of season one Willow: a geek with pretensions of being cool.

|

| Dream-Willow delivering a book report |

In her dream,Willow is dressed in schoolgirl clothes, delivering a book report on The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.Anya and Harmony are snarking at her from the audience, Buffy is bored, Xander is shouting, “Who cares?!” and Tara and Oz are mocking her and flirting wit heach other.

This sequence is haunting, heartbreaking, and foreboding. Those of us who watched Buffy for the first four years know that Willow’s perceptions are far from accurate. Buffy was supportive of Willow far more often than not and Xander defended Willow against anyone who threatened her. As for her love interests, well, Tara practically worshiped the ground Willow walked on, and Oz admitted that Willow was the only thing in his life that he ever loved.

But none of that changes the way Willow feels. Despite the friends she’s made, despite thechanges she’s had, she still thinks that everyone will eventually discover her secret: that she’s an uncool, childish, awkward geek.

I think that this fear, more than anything else, is what motivates Willow’s actions over the second half of the series. The show talks about magic addiction and getting high off of power, but ultimately, Willow wants to change who she is. She doesn’t want to be the nerdy, lonely bookworm that defined so much of her childhood and adolescence. She jokes to Tara, “Hard to believe such a hot mama-yama came from humble, geek-infested roots?” and she might as well be pleading, “I’m not that geek anymore, am I? Tell me I’m not.” She says to Buffy, “If you could be, you know, plain old Willow or super Willow, who would you be?…Buffy, who was I? Just some girl. Tara didn’t even know that girl.”

|

| Willow talks to Buffy after coming down from a high |

Eventually, Willow confronts her addiction and power issues with magic. Her arc in the last season of the show is largely about the way she learns to be more careful with magic, her steps forward and her steps back, until she handles her power more responsibly. But one thing she never does is confront her deepest issue: her fear of being an unlovable geek.

I could write for another two thousand words about how Willow’s insecurities made her dangerous to people around her, and how her arc paralleled the arc of the three misogynistic sci-fi geeks who provoked terror all throughout season six, and how her fear of abandonment turned her into the abuser in a controlling relationship, but that’s an essay for another day. I will probably write that essay in the future, but for now, I want to talk about how Willow’s insecurities affected Willow.

A part of me feels truly sad that Willow could never find it in her to reclaim the geek label. I look back at the cute, eager computer nerd from the first two seasons and feel nostalgic for her Hermione Granger-like enthusiasm. I wish she had felt comfortable enough in her own skin to realize that being smart and knowing a lot about computers is a good thing, dammit!

At the same time, I wonder if there’s another lesson in Willow’s story. Audience members like me might yearn for the days when Willow was more interested in computers than she was in magic, but who’s to say that hacking and breaking into government files was the best way for Willow to spend her life? Sure, she was good with computers, but did she had to let that skill define the rest of her life? Isn’t it positive for her to branch out and explore that she has talent in other things in more than one area? After all, even if we’re nostalgic for Willow’s nerdier days, doesn’t she have the right to explore other sides of herself, even if she makes mistakes along the way?

To this day, I still don’t know how I feel about Willow’s arc. I’m glad she discovered another side to her personality, but I’m disappointed that she couldn’t reclaim her geeky days and make it a source of power instead of embarrassment and loneliness. Ultimately, I would have liked to see the show address Willow’s “geek-infested roots” in the last season of Buffy,so we could have seen her make a choice about that part of her life and her identity, instead of seeing that part of her character fall to the wayside.

Lady T is an aspiring writer and comedian with two novels, a play, and a collection of comedy sketches in progress. She hopes to one day be published and finish one of her projects (not in that order). You can find more of her writing at The Funny Feminist, where she picks apart entertainment and reviews movies she hasn’t seen.