|

| Best Picture nominee Slumdog Millionaire |

This is a guest post from Tatiana Christian.

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Best Picture nominee Slumdog Millionaire |

This is a guest post from Tatiana Christian.

|

| The Curious Case of Benjamin Button |

This is a guest post from Jesseca Cornelson.

Once I settled into the movie, however, I was able to enjoy it like the popcorn fare that it is—pleasant, but not terribly complex and with little nutritional value. My very first impression of the film was that it is one of those movies whose story is designed simply to make the viewer cry, and for me, it succeeded quite effectively in that regard. I’m a sucker for stories shaped like sadness. My second impression was to wonder why on earth I was being made to cry about the tragic love story of two imaginary white people against the back drop of Hurricane Katrina, which was a very real and epic tragedy for the city this story is set in (as well as for areas well outside New Orleans). To this second point I will return shortly.

But first, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, based on a short story of the same name by F. Scott Fitzgerald, bears a family resemblance to another film adaption of a literary source, Forrest Gump, so I wasn’t terribly surprised to find out that screenwriter Eric Roth penned both films. In each film, we follow a quirky white boy in the south from his childhood through his adventures in adolescence and early adulthood and on into maturity. Covering such a large time span, the plots are largely episodic in nature but the feeling of an overarching structure is achieved through the protagonist’s varied and lifelong relationship with a woman he’s known since childhood. Both Benjamin’s Daisy and Forrest’s Jenny are remarkable, I think, only for their beauty and their rare understanding and appreciation of their respective misfit men. Both films also present what I think of as problematically unproblematic racial relationships. I don’t necessarily believe that every film, much less those that are comedic or fantastical in nature, needs to radically explore gender and racial relationships and stereotypes, but I suppose I don’t believe that we’re sufficiently post-racial to be able to gloss over historical struggles without such glossing over itself feeling like a distraction. And I think that’s part of what renders both TCCOBB and Forrest Gump ultimately conservative films.

Before I take on what I think is Benjamin Button’s most interesting relationship—that with Queenie, the African-American woman who adopts him, I want to talk about the film’s magical realism. While TCCOBB is clearly grounded in familiar historical periods and places—1918 New Orleans, Russia pre-World War II, a Pacific marine battle (if I recall correctly), not to mention the frame story set in a 2005 New Orleans on the brink of Hurricane Katrina—the world Benjamin Button lives in is also one of magic and wonder. In the frame story, Daisy’s daughter reads to her mother from Benjamin’s diary as Daisy prepares to die. The narrative in Benjamin’s diary is further framed by the story of Mr. Gateau’s backwards running clock, built out of Mr. Gateau’s desire for his son who died in World War I to return to him. Presumably, this backwards running clock had some kind of magical influence over Benjamin, who was born the size of a baby but with the features and ailments of an old man and, as anyone who is remotely familiar with the film’s concept knows, appears to grow younger as he in fact gets older. [I have to admit that I totally thought Benjamin was going to end up as a man-sized baby at the end, an idea I got from reading too much Dlisted where Michael K would go on and on about Cate Blanchett as an old lady having sex with Brad Pitt as a old man baby. Oh, Dlisted, I can’t believe I believed you! Also, try as I might, I cannot find the posts where Michael K says this, so maybe I imagined the whole thing.]

Other than these very important magical elements, the universe of TCCOBB is relatively realistic, save for its gliding over of both the women’s movement and the Civil Rights Movement. What are we to make of this? The way I see it, since TCCOBB works hard to incorporate historic events like World Wars I & II and Hurricane Katrina, (1) the filmmakers don’t think that race and gender figure very largely in 20th century and early 21st century American history; (2) they imagine that in the same magical world where a baby can be born with the features and ailments of an old man, issues of gender and race are magically non-issues; or (3) since this is Benjamin Button’s story, he just doesn’t give a crap about race and gender. Choice three is definitely the least plausible. Benjamin Button is one very nice guy who definitely gives a crap! (Maybe the point is “Here is a really nice white guy!”) He loves his black momma Queenie (as portrayed by Taraji P. Henson)! He loves Cate Blanchett’s Daisy, even when she’s an unlovable prick. I sympathize with filmmakers and writers of all kinds, for that matter, who want to tell stories set in the historic south about something other than race. Must every story set in the historic south be about race? No, certainly, I don’t think so. But when race comes up—as it most definitely does here since Benjamin is adopted by an African-American woman—it seems strangely unrealistic to neglect the complexity of historic race relationships.

Maybe the question I should be asking is what purpose does Queenie’s blackness serve? Does her blackness make her more accepting of Benjamin when even his own father abandoned him and others were repulsed by him? Does it make the film feel integrated and inclusive while still focusing mostly on white experience? Perhaps it’s better to ask what possibilities might Queenie’s blackness have presented in this magical version of historic New Orleans. If historical gender and racial issues are going to be ignored, I think it’s an exciting possibility to think of how they might have been re-imagined altogether. That’s one of the great possibilities of speculative fiction: it allows us an opportunity to imagine how else we might be—both in utopic and dystopic senses. But even as TCCOBB neglects historical oppression, it also fails to present an imaginative alternative, and that feels like a missed opportunity.

Essentially, Queenie, as a black woman, is limited in her employment as a servant to whites. And even though she fully accepts Benjamin as her son and Benjamin does seem to love and appreciate her, he seems to fail to see how the world treats her differently and, as he grows up, he surrounds himself with white people, almost forgetting about Queenie altogether. Ultimately, the stereotype of the nurturing black woman as a loving caretaker of whites is not greatly challenged or expanded upon. African Americans are presented largely as servants. And they are truly only “supporting” characters for the white characters. Benjamin doesn’t seem to see African-American women as potential lovers or mates—only as mother figures, or rather as his mother, since the only African-American woman presented in any kind of depth is Queenie. Most strikingly, he doesn’t use his inherited wealth to get Queenie her own place or otherwise take care of her, and the last time we see Queenie, she serves Benjamin and Cate cake before retiring to bed. My heart broke for Queenie that Benjamin didn’t see to her retirement in the same way that he looked after Daisy. Is TCCOBB saying that a black woman’s motherly love is expected for free but the romantic affections of a white woman are worth money? Certainly, I think the film suggests that while black women may make good enough mothers for white boys, those boys will grow up only to desire white women. Or perhaps the film simply suggests that black women are perfectly acceptable as caretakers, but they aren’t sexually desirable like white women are. If that last sentence seems far-fetched, think about how the black women who are seen as sex symbols in our culture have or affect features often associated with whiteness. At very least, it seems that the role of lover is elevated above that of mother.

This could have been a more radical movie—and not just one in which a white character has a revelation about what it’s like to know and love black people but one whose very imaginings might show how our racial conceptions and constructions might be otherwise. Instead, we get the opposite: race relations are sanitized of all conflict, while the segregation of family and romantic relations is upheld, with the sole exception of Queenie and Benjamin.

Queenie’s preposterous explanation that Benjamin is her sister’s son “only he came out white”—possibly the film’s most hilarious moment—suggests a missed opportunity. What if in this imagined world black women commonly had white babies and vice versa? Even in our own world, racial designations aren’t as clear cut as we often assume them to be. (See “Black and White Twins”; “Parents Give Birth to Ebony and Ivory Twins”; “Black Parents . . . White Baby”; and “My Affirmative Action Fail”.) What if TCCOBB totally upended everything we think we know about race and women’s roles in the south of the past? Wouldn’t that be interesting?

Moreover, it’s one thing to neglect race and gender issues of the past, but what about in the frame story of the present? All of the nurses and caretakers in Daisy’s hospital are also black women. Daisy is kept company by her daughter, Caroline, and a black woman the same age as Caroline, who eventually leaves to check on her son and never returns to the movie. WTF? Why is she there? Is she Caroline’s girlfriend? A good friend? If we’re not going to see her again, why is she there in the first place? Okay, I looked up the script. For what it’s worth, it specifies that she’s “a young Black Woman, a ‘caregiver,’” though nurses in scrubs are also present and Dorothy dresses in civilian clothes and spends most of her screen time thumbing through a magazine. I so wish that Dorothy had been Caroline’s girlfriend or wife.

And what of Hurricane Katrina? In the end, all we see is water rising in a basement, flooding the old train station clock. There’s nothing about what happened in the hospitals, in the Ninth Ward, in the attics, in the streets, in the Superdome. I don’t even know what to say about that. That the preposterously tragic love of two imaginary white people trumps and erases all the suffering of real, mostly black people? Even through my great big ole sappy tears as Daisy dies, that just doesn’t feel right to me.

Finally, I am reminded that part of my reluctance to watch The Curious Case of Benjamin Button lies with its format as a film. Over the past decade, I’ve grown to prefer serial dramas to just about everything—film, books, whatever (though I’ve recently become consumed with popular fantasy and horror novels). HBO led the way and remains at the top of the serious television game. Deadwood and The Sopranos developed true ensemble casts with richly developed morally-complicated characters shaped by their social, historic, and economic milieux, with deft dialogue that could be emotionally moving or belly-shaking hilarious. The mere invocation of Hurricane Katrina makes it impossible for me not to compare the long but ultimately light fare of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, which aside from its technical and artistic wizardry is ultimately forgettable, with the robust, lifelike, brilliant work of art that is Treme. Where TCCOBB uses its historical setting like a painted backdrop to affect historic depth without actually engaging history, Treme is a masterpiece of the fictionalized drama of the everyday real life of one of America’s great cities. Where women and African Americans are given roles in TCCOBB that support white stars, every character in Treme’s diverse cast is treated as the star of his or her own life, and they are richly complicated people whose lives are never defined solely by their relationship to white main characters. So that’s my loopy recommendation about The Curious Case of Benjamin Button: you’re better off watching Treme.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button was nominated for thirteen Academy Awards in 2009. It won three Oscars for art direction, makeup, and visual effects. It was nominated for cinematography, costume design, directing, film editing, original score, sound mixing, best picture, best actor in a leading role, best actress in a supporting role, and best adapted screenplay.

Stephanie Brown is the author of two collections of poetry, Domestic Interior and Allegory of the Supermarket

. She’s published work in American Poetry Review, Ploughshares and The Best American Poetry series. She was awarded an NEA Fellowship in 2001 and a Breadloaf Fellowship in 2009. She has taught at UC Irvine and the University of Redlands and is a regional branch manager for OC Public Libraries in southern California. She grew up in the same area as Richard Nixon and lives in San Clemente, where the Western White House still stands at its southernmost shore.

This is a guest post from Megan Kearns.

|

| Juno |

It turns out, however, that after an initial adjustment period to the dialogue (and a question about whether the film is set in the early ‘90s), Juno turns out to be planted in a feminist worldview, and is a film that teenagers, especially, ought to see. It was thoroughly enjoyable, funny and touching. I liked it so much that I watched it again, but when I started to write about it, what I liked about the movie became all the more confusing. I loved the music, although Juno MacGuff is way hipper than I was (or am), and I saw a representation that reminded me of myself at that age. I saw a paternal relationship that I never had and a familial openness that I’ve also never had. I saw characters who I wanted as my childhood friends and family.

It turns out, however, that after an initial adjustment period to the dialogue (and a question about whether the film is set in the early ‘90s), Juno turns out to be planted in a feminist worldview, and is a film that teenagers, especially, ought to see. It was thoroughly enjoyable, funny and touching. I liked it so much that I watched it again, but when I started to write about it, what I liked about the movie became all the more confusing. I loved the music, although Juno MacGuff is way hipper than I was (or am), and I saw a representation that reminded me of myself at that age. I saw a paternal relationship that I never had and a familial openness that I’ve also never had. I saw characters who I wanted as my childhood friends and family.  The film’s real progressive moment comes when Juno realizes that her idea of perfection isn’t perfect. She realizes that a father who doesn’t want to be there would be as bad as a mother who hadn’t wanted to be there. She sees that a father isn’t a necessity–or perhaps simply that two parents aren’t a necessity. Yet what does this all add up to mean? There’s certainly a moment of female solidarity (and this isn’t the only one, certainly, in the film), and a difficult decision that she makes independently. But, as with other conclusions I’ve made, I’m left with the question of “So what?”

The film’s real progressive moment comes when Juno realizes that her idea of perfection isn’t perfect. She realizes that a father who doesn’t want to be there would be as bad as a mother who hadn’t wanted to be there. She sees that a father isn’t a necessity–or perhaps simply that two parents aren’t a necessity. Yet what does this all add up to mean? There’s certainly a moment of female solidarity (and this isn’t the only one, certainly, in the film), and a difficult decision that she makes independently. But, as with other conclusions I’ve made, I’m left with the question of “So what?”

I’d like to start this review with a confession: Atonement is the second book in my long history of reading that has made me so angry, so upset, that I literally threw it across the room.

Both as an Academy Award-nominated (and winning, for soundtrack) film and as a book adaptation, Joe Wright’s Atonement succeeds. The film is a gorgeous and gritty, if frustrating, portrait of childhood, of war, of love, of lies and the lies one tells to correct them.

The first section of the film and novel set up the plot. The wealthy Tallis family has temporary custody of their lesser-off red-headed cousins, the Quinceys, and young Briony (Saoirse Ronan) is determined to lead them all in a play to celebrate her older brother Leon’s homecoming. Mother Tallis is sick in bed, and older sister Cecilia (Keira Knightley) is awkward around the son of the Tallis’s lawn worker, Robbie (James McAvoy) and excited to hear that her brother is coming home, despite news that he’s bringing along a friend, cocky Paul Marshall.

In direct contrast to this innocence comes Paul Marshall, introduced as a dapper gentleman who intends to make money off of the war with his Army Amo chocolate bar factory. He descends upon the safe haven of the nursery where Lola is meant to be watching over her twin brothers. “You have to bite it,” he says, handing her a bar of chocolate, his face stony.

The sexuality, too, of Robbie has another angle. His attempts at a polite apology devolve quickly into crude sexual expression. Robbie is faced with the sheer absurdity and irrationality of expressing sexual attraction to one who is of a higher class. Paul Marshall experiences the opposite problem, his power over Lola used to his advantage as he inflicts first rough treatment and then a rape in the woods. That power keeps Lola from seeing the truth, that she has been mistreated, brutally; Paul Marshall keeps Lola at his side, and she eventually marries him.

What follows is Rob and Briony’s means of atoning for their crimes. Rob, unable to fight the accusation against the wealthy and certain young Tallis, is sentenced to prison and then to fight in WWI. Briony, realizing years later that there were cracks in what she witnessed, that there are, perhaps, alternate truths, becomes a nurse in an attempt to undo some of the wrong she has inflicted upon Cecilia and Robbie.

A story is being crafted, an attempt to fill in the blanks. An attempt to create rational cause and effect as happens in all stories when we are young. An attempt to understand what must be truly random and unpredictable. Motive must be established.

But of course, things don’t follow a logical order. The wrong person is blamed for a tragedy while another gets off scot-free. War happens and the best and worst of us are lost, caught in causes we might not respect ourselves. Illness, a car crash, a lightning strike. Do we blame Briony, then, for trying to set order in her confusing world? Do we blame her for attempting to set things right that she helped to set wrong? I remember upon first completing the novel, my rage was so complete, so strong. I hated Briony for what she had done, for creating ugly and beautiful lies to cover up the truth, for believing that life was as simple as “Yes. I saw him with my own eyes.” I hated Briony for the very reasons that I love reading and watching films: writers and directors create lies for us, and we indulge in them. Fiction is called such for a reason–it isn’t real.

The soundtrack, interlaced with the sounds of a typewriter, never lets us completely forget that this is a story that is being crafted. It is no mistake that the first shot of the movie is Briony typing away at her play, “The Trials of Arabella,” taking her work very seriously. Briony expresses the difficulty of writing: that a play depends on other people.

The difference between play and story, as Briony postulates, are similar to the difference between novel and film. McEwan spends pages describing the intricacies of the vase, complete and then broken, whereas in a film, the vase is simply there. A long camera shot transports the viewer from room to room; instead of the turn of pages, the soundtrack interacts with the actions on screen instead of, for example, a rowdy neighbor or interrupting child pulling attention from the work.

While it is, in a way, refreshing to give the narrative over so completely to a woman in what is most certainly not a “chick flick,” and while Cecilia appears to be a strong, fierce woman in charge of her own sexuality, and while Briony, if not the most trustworthy of narrators, is more than skilled enough to do the job of telling this story, both of their stories center around Robbie. Even small conversations between Briony and Cecilia, Briony and Lola, Briony and a young nurse at training devolve quickly into a discussion of Leon, or Robbie, or marriage.

Any deconstruction of the traditional romantic narrative does have the potential to be feminist, however in this case, because the story is filtered not only through Briony Tallis’s obsession with that very narrative but through a male author and director, the deconstruction is seen as a loss of something good. A loss of cherished innocence, of childlike femininity.

There is no denying the technical mastery of Atonement. Simply look at the long shot as Robbie arrives at Dunkirk, despair and small hope surrounding him and swooning around him as the camera floats through soldiers waiting. Look at small consistent hints of cracks in the narrative, look at changes in perspective looped together by setting and soundtrack. Atonement is a master work of fiction and of film, but feminism is not something I believe it can claim.

|

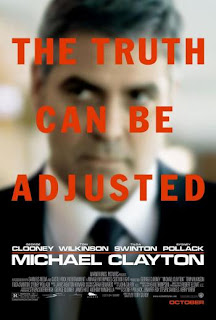

| Best Picture nominee Michael Clayton |

|

| Best Picture Oscar nominee, There Will Be Blood |

I’m one of those hothouse flower film enthusiasts who feel relieved whenever Citizen Kane comes on Turner Classic Movies, as if it were a remedy for my chronic migraine. I’m oddly grateful to Ted Turner (my undergraduate commencement speaker and an American mogul/eccentric much like Kane and Plainview) for TCM, though I find myself muttering after I’ve clicked back over to, say, some Jennifer Aniston rom-com, “What happened to Hollywood?” Sure, it’s a cliché of a question, but the answers are myriad and complicated, having mainly to do with changes in the culture and in the medium itself. There are certain images, ideas, and obsessions that are inherent to our collective identity as a nation, and every once in a great while contemporary filmmakers who happen to have the money, the talent, the connections, and the audacity, explore them with varying degrees of success. P.T. Anderson’s 2007 Oscar-winning There Will Be Blood is one if those movies, a masterpiece in the tradition of Welles’ Citizen Kane and, yes, I can without hesitation tell you that I absolutely adore it. Classic Hollywood lives on.

There Will Be Blood is loosely based on Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel Oil! Though I haven’t read the novel, I do know that while adapting the material for his screenplay, Anderson chose to concentrate on the troubled and troubling relationship between Daniel Plainview, a self-made oilman played to perfection by a John Huston-inspired Daniel Day Lewis, and his more politically and emotionally progressive “son,” H.W., rather than the Teapot Dome Scandal of the 1920’s; it was an important and effective choice. During the first ten minutes of the film, Anderson provides us with all the exposition we’ll need through a largely dialogue-free sequence in which we’re witness to the crudity and danger of early American oil exploration, our main character’s relentless vigor and drive, and H.W.’s entrance into Plainview’s life as an infant orphaned by an oil-well accident. The final scene in the opening sequence is masterful: Daniel Plainview alone on a train with H.W. as a baby tucked into an open suitcase. H.W. plays with Daniel’s mustache as Daniel looks down on him with tenderness. Right from the start, Anderson is confounding our initial assumptions about Daniel specifically and about turn-of-the-century oilmen in general, by juxtaposing ruthlessness with familial love and loyalty. This is, after all, a movie in which conflict is created and developed via a collection of Biblical proportioned antagonisms—father v son and brother v brother. The film ultimately ends with the dissolution of any real (or imagined) family connection between Daniel and H.W. in lieu of a philosophical (and literal) battle of sorts between two conmen—Daniel Plainview the oilman, and Eli Sunday the preacher (played by the excellent Paul Dano. Dano, who can go toe-to-toe with the finest screen actor working today, is definitely one to watch.)

It’s important to pause here and mention changing views concerning the portrayal of women, minorities, the disabled, and the disenfranchised at large in American films. If we consider some of our American cinematic “masterpieces,” we often find them absent vibrant female characters, for example (think The Godfather, Citizen Kane, and Chinatown to name just three). As much as I desperately want to see my gender portrayed with respect, honesty, and integrity, many films that deal with the great American mythos don’t have much room for female characters, simply because women haven’t been a part of, and are often still excluded from, the creation story we tell ourselves—a story of brutal boots-on-the-ground capitalism and, negatively speaking, punishing exploitation. It’s a Judeo-Christian story in which the individual male forges his path through the wilderness, an anti-hero who, despite his great wealth and power, can’t overcome his subsequent moral corruption. What’s important to recognize is that the marked absence of “the other” in these films is a comment on an institutionalized patriarchy that extends beyond our everyday interactions to the very heart of our cultural mythos. There Will Be Blood is yet another film that further cements a white male-dominated American story of origin.

But what makes this particular film so thrilling is that it’s ultimately much more than a postmodern cop to an earlier American form; it’s a visceral, earnest portrayal of the forces at work in opposition to, and in support of, our American fantasy of self-sufficiency and self-reinvention. Anderson creates a highly stylized world in which a boy can seemingly spring from Plainview’s oil well, sans womb, in a sort of male Immaculate Conception. It’s a Cain and Abel world (though the twentieth century has already obscured the moral clarity of earlier epochs) where blazing fire erupts from great swaths of desert and where men, faces blacked by oil, seem to crawl up from the earth’s very crust. It’s a film that leaves us wondering which of the two “brothers” is more evil: Paul or Eli? Daniel or Henry? What I mean is, at its core, There Will Be Blood describes the convoluted love/hate relationship between capitalism and Eli Sunday’s frontier-style Christianity. Who will win in this war for men’s (and women’s, I guess) souls?

Both Daniel and Eli vie for the hearts, minds, and pocketbooks of Little Boston’s citizens, most effectively illustrated in the scenes between Daniel, Mary Sunday, and Abel Sunday—Mary and Eli’s father. Mary is really the only female character who gets any airtime in There Will Be Blood and, like the rest of the movie’s characters, she’s given a name with Biblical significance. As an innocent, she’s a likely victim and both her religious family and the faithless Daniel Plainview, attempt to use her as an example. When H.W. tells Daniel that Abel “beats her [Mary] when she doesn’t pray,” we watch Daniel’s wheels start to turn. As a slap-in-face to Eli, Daniel invites Mary to stand with him at the well’s christening, instead of allowing Eli to lead his “congregation” in prayer, and later, at the picnic, Daniel makes a point to tell Mary he’ll “protect her” from her father while Abel’s still in earshot. We could interpret Daniel’s gestures of warmth and affection toward Mary as genuine—after all, he was willing to take orphaned H.W. on as his son—but Anderson doesn’t shy away from also suggesting that Daniel is perfectly willing to use the cult of familial loyalty to win trust for financial gain—a savvy ploy we see time and time again in films like The Godfather, Chinatown, and, yes, Citizen Kane. It’s an ultimately destructive ruse and Daniel falls victim to it, naturally, in the end.

When H.W. is made deaf by another oil well accident, Daniel finds him to be a less than effective business partner, though Anderson and Day-Lewis endow the character with so much fervent contradiction, it’s hard to tell how Daniel really feels about his son’s handicap. Later, when a stranger approaches Daniel to tell him he’s his long-lost stepbrother, we can tell, in his own convoluted way, that Daniel is looking for an opportunity to trust—somebody, anybody—while he claims, of course, to have disdain for “these people.” And finally, after his own self-delusion proves, well, illusory, and he’s bereft of his “son” and his “brother,” (dispatched by his own hand, no less), we watch Daniel rage further into a kind of Charles Foster Kane-type isolation. The film closes with a terrifying scene that frankly verges on bathos (it takes place in Plainview’s private bowling alley of all places) in which Daniel forces Eli to submit, aloud, that he is “a false prophet” and that “God is a superstition” after Eli attempts to extort money from his old enemy.

Anderson has proven his tremendous potential with There Will Be Blood, so much so, I wonder how, after plumbing the bloody depths of our Great American Hang-ups, he could possibly top its achievement. It’s a difficult film and most likely not to everyone’s taste, but it’s a film I’m certain will age well thanks to its satisfying complexity and nuance. “Give me the blood,” indeed!

|

| Best Picture Oscar Winner, No Country For Old Men |

Cormac McCarthy doesn’t understand women.

Statements like this are responsible for the ever-growing dent in my desk and the permanent lump on my forehead. McCarthy is a very highly respected writer. He’s won the Pulitzer Prize. He’s a MacArthur Fellow. He’s been compared to Faulkner, Joyce, and Melville. Can you even imagine a female writer garnering such acclaim without writing a single prominent male character, and then telling Oprah, “I don’t pretend to understand men”?

The Coen brothers, happy to say, make no such nonsense generalizations about 50% of humankind. Not only did they create one of my favorite female characters of all time in one of my favorite movies of all time–Frances McDormand’s Best-Actress-Oscar-winning turn as Marge Gunderson in 1996’s criminally non-Best-Picture-winning Fargo–but they often portray prominent female characters in their films: notably in Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Burn After Reading, and last year’s True Grit.

The union of Cormac McCarthy and the Coen brothers is, aesthetically and thematically, an excellent idea. No Country For Old Men the novel, with its sparse and evocative prose, reads like a treatment for a Coen brothers film. Violence, greed, fate, and the average joe who gets caught up in criminal activity are all recurring Coen motifs, even if the unremitting bleakness leaves almost no room for their characteristic gallows humor. However, as Ira Boudway’s Salon review puts it, in the novel’s milieu “[w]omen exist mainly to show primordial attraction and inarticulate loyalty toward men; men are more at ease sawing off shotgun barrels or dressing their own bullet wounds than they are in the presence of women, children or their own emotions.”

That’s as true of the film as it is of the book. In McCarthy’s portrayal of rural West Texas, 1980, women are receptionists, secretaries, loyal wives, and not much else. A handful of women make single-scene appearances in this movie to serve coffee or give motel room keys to the three main characters: average joe Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), old Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones, sporting a permanent worried frown that makes you want to hug him and feed him Snausages), and serial killer Anton Chigurh (a spine-tingling Javier Bardem). The only woman who really has something to do in the film is the wonderful Kelly Macdonald, whom you can witness being wonderful to the max in the terrific Boardwalk Empire (roll on fall!).

Of course, when I say “something to do,” I mean “a grand total of ten minutes’ screentime, all of it oriented to onscreen husband Brolin.” As Carla Jean Moss, Macdonald bears an expression of chronic worriment to rival Jones’s, and almost all of her scenes require her to do nothing more than fret at Brolin, asking him for guidance or expressing concern for his safety.

In a way, Carla Jean ties the film together, but she does so solely in terms of the male characters: she is the only character to share screentime with all three of the main characters (who never appear onscreen together). Occasional hints are dropped regarding her life outside of the men–“I’m used to lots of things. I work at Wal-Mart”–but, frustratingly, these are not expanded in any way. Only in her final scene does she talk about something other than Llewelyn.

Those three main characters are all men with a mission. Llewelyn’s mission is as simple as staying alive: stumbling on the scene of a drug deal gone kaput, he swipes a satchel full of cash, and in that singularly ill-thought-out action of basic greed he finds himself a hunted man, pursued by the chillingly ruthless and single-minded Chigurh. He in turn is hunted by Sheriff Bell, who is haunted by an existential crisis born of his age and sense of his own mortality. Of the three, only Chigurh operates within a clear and unambiguous moral code. Bell feels overwhelmed by the unremitting violence of his county and plans to retire, and Llewelyn dooms himself with an act of kindness (returning to the scene of the drug deal to help the wounded man who had earlier begged him for water, thus gaining the attention of his pursuers); Chigurh, though, shows no weakness or indecision, but complies fully with a set of inflexible rules.

In perhaps the movie’s most famous scene, Chigurh asks a too-observant store owner, “What’s the most you ever lost on a coin toss?” When the owner calls the toss correctly, the hitman abides by the coin’s ruling and lets him live. By allowing external cues–the sound of a toilet flushing, the ringing of a phone, the result of a coin toss–to determine his actions, Chigurh presents himself as an instrument of fate. In fact, he can be read as the personified figure of Death itself, hunting down his victims with absolute implacability, killing or sparing them on the basis of chance outcomes that invoke chaos theory and the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Over the phone, Chigurh offers Llewelyn a deal: “You bring me the money, and I’ll let [Carla Jean] go. Otherwise she’s accountable, same as you.” Even after Llewelyn is dead and the money has been recovered, Chigurh’s moral code demands that he honor the terms of this deal, and he hunts down Carla Jean.

If Chigurh is, as I read him, not Death itself but a man who believes he is enacting the works of Death on earth, then Carla Jean is the one character to call him out on this. Llewelyn, the store owner, bounty hunter Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson)–all operate within Chigurh’s framework, trying to trick him or compromise with him, accepting the rules he gives them: “You need to call it. I can’t call it for you. It wouldn’t be fair.” Only Carla Jean refuses to engage, declining to call the coin toss and telling him, “It’s not the coin [that determines your actions]. It’s just you.” It’s a fascinating glimpse into her character, which remains frustratingly underdeveloped, because recognizing the arbitrary nature of the rules does not free her from them.

The film’s final scene is of now ex-Sheriff Bell talking to (or possibly at) his wife Loretta over breakfast, aimless in his retirement. He describes his dreams of his late father, who “was goin’ on ahead and he was fixin’ to make a fire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold, and I knew that whenever I got there he would be there. And then I woke up…” His world has no place for an older man, for a sense of morality or law as he knows it. He might well be asking himself the question Chigurh asks of Wells, moments before killing him: “If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?”

Fargo ends similarly, after all the action and thrills are played out, with a moment of intimacy between law officer and spouse. The tone of the two endings, however, could hardly be farther apart: Ed Tom Bell ends No Country a defeated man, adrift in a harsh and incomprehensible world, with death the only blessing on his horizon; Marge Gunderson ends Fargo smiling, sharing in her husband’s little triumph, and saying, “Two more months.” Fargo offers hope and redemption for humanity in the suggestion that there is indeed more to life than a little money, whereas the philosophy of No Country For Old Men is summed up by an old white man complaining bitterly about “the money, and the drugs…[and] children[…]with green hair and bones in their noses.”

Max Thornton is about to move halfway across the world to be a grad student. She writes words at Gay Christian Geek.

Incendies: Lebanon Is Scorched, Burned and Blistered

|

| A cinematic moment. The image comes first and the explanation comes much much later. |

|

| Violence and pain become sources of empathy and identification for the audience. |

|

| The now classic diasporic subject returning to the ‘homeland’ and looking. |

|

| The protagonist is played by Lubna Azabal, a Moroccan actress who is a contender to be the next generation Hiam Abbas. Hiam Abbas is the Arab world’s Meryl Streep. |

Just after the death of her newly-born sister, Chanda, 12 years old, learns of a rumor that spreads like wildfire through her small, dust-ridden village near Johannesburg. It destroys her family and forces her mother to flee. Sensing that the gossip stems from prejudice and superstition, Chanda leaves home and school in search of her mother and the truth. Life, Above All is an emotional and universal drama about a young girl (stunningly performed by first-time-actress Khomotso Manyaka) who fights the fear and shame that have poisoned her community … Directed by South African filmmaker Oliver Schmitz (Mapantsula), it is based on the international award winning novel Chanda’s Secrets by Allan Stratton.

By Liz Braun:

Life, Above All is an historical snapshot of the AIDS crisis in Africa and an indictment of sorts of the government bungling that allowed the epidemic to overwhelm South Africa. The culprits (ignorance, poverty, big pharma, religious and political leaders, etc.) are not so much the focus; the point of this quiet, heartbreaking drama is all those children left to cope, especially the orphans.

By Nora Lee Mandel:

Rather than focusing on the usual corrective lessons on the transmission and treatment of HIV/AIDS, the family’s struggles play out within systems of traditional care and limited modern medical facilities that are strained to the breaking point. Chanda rails against the stoic comforts of religion and receives only discouraging advice at an overcrowded clinic. Her illiterate and exhausted mother falls prey to the greed of a charlatan doctor, a demon exorcism, and horrific neglect by her revengeful sister, who has not forgiven Lillian for her flouting of tribal marriage traditions for the sake of love.

By Manohla Dargis:

Chanda’s silence is unnerving, as is the absence of tears, and while her calm conveys a preternatural strength of character it also suggests a lifetime of pain. No child, you think, should have to pick out her baby sister’s coffin. But she does, taking in the horror of the funeral home and its metal table without flinching and then pushing forward, still dry eyed, still determined, taking on life with an appealing (and enviable) toughness and grace that make this difficult story not just bearable but also absorbing. As the weight of the world bears down on her slender frame, she becomes the movie’s moral compass and its authentic wonder: the child who is forced to be an adult yet remains childlike enough to feel real.

By Mary Corliss:

Two years ago, a drama with a seemingly forbidding subject — an illiterate teenage girl, pregnant with her father’s child and hellishly abused by her drug-addicted mother — won over critics, audiences and the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The film was Precious. Now comes Life, Above All, which deals with the tragedy of AIDS in South Africa, as seen by a 12-year-old girl named Chanda. At the end of its world premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, critics cheered like schoolkids, giving it a 10-minute standing ovation.

By Alison Willmore:

… when its focus narrows onto Manyaka and her mother (Lerato Mvelase), their deep mutual affection and the terrifying sacrifices they’re ready to make because of it, the film sings, becoming a moving tribute to love holding fast against suffering. The ending, which offers a hint of relief, is unfiltered, frankly unbelievable melodrama, but something grimmer and more measured would be intolerable after everything that comes before.

|

| Good Dick (2008) |

For the lead male role I wanted to see the lover archetype illustrated in a way that is all loving, all kind, all ways. I knew the guy had to be strong and thereby protective, but not in a stereotypical sense. Definitions of masculinity often tend to be deformed in our culture, forgetting the good fight and glorifying what I like to call, “The cardboard cutout man.” In Good Dick the man’s power has nothing to do with his physical strength, his appearance or his social status. He is masculine in a way that is genuine; this masculinity stems from his lack of chauvinism. His chivalry is his depth of kindness.