This cross-post by Andé Morgan previously appeared at her blog No Accommodation and appears as part of our theme week on Child and Teenage Girl Protagonists.

Enter the Wayback Machine in your mind and go back to 2011. This was an era with only one Smurfs and only two Hangovers. More original fare like Rango and Super 8 was somewhat overshadowed by superhero movies, which were HUGE, and the sequelmatic masterpieces that were Transformers: Dark of the Moon and Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides. That’s OK, originality is overrated. For example, my favorite wide release of late 2010-early 2011 was True Grit. Based on the 1968 serial novel by Charles Portis, True Grit the movie had been done by The Duke in 1969. And by done I mean it did well; it was a financial and critical success and gave John Wayne his only Oscar. Nevermind that the script was less than faithful to the source material, or that Mammon possessed Paramount to spawn a horrific sequel, Rooster Cogburn.

Let me get my bias out front: I am a fan of the Coen Brothers, but I don’t always drink the Kool-Aid (am I the only person who thought Fargo and No Country for Old Men were just OK?). However, I loved True Grit. I don’t think it is hyperbole to call it a masterpiece. It represents an increasingly rare combination of excellent screenwriting, gripping cinematography, high production value, and masterful acting in a wide release film. Its story of vengeance is timeless, but the setting is as uniquely American as apple pie, Duck Dynasty, and gun violence.

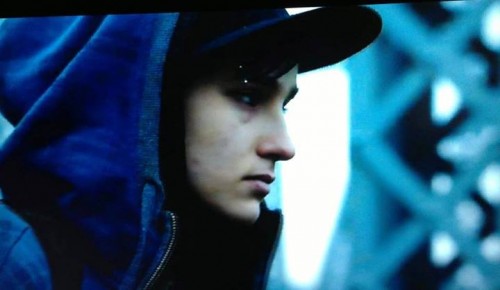

To summarize: in the American Old West (Oklahoma and Arkansas were part of the Old West in 1877), Mattie Ross (played by Hailee Steinfeld in the 2010 film) loses her father when he is murdered by his hired hand Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin). She enlists the help of U.S. Marshal Rooster Cogburn (Jeff Bridges) and Texas Ranger La Boeuf (Matt Damon) to bring the fugitive Chaney to justice. Because she is an adolescent female, no one takes her seriously until the strength of her persistence wins out. Vengeance is hers in the end, but not without cost.

All of the incarnations of True Grit are popular fodder for analysis from a feminist perspective not only because it is well-known and well-respected as an “American” story, but also because it is an unusual story. It features a young, female protagonist with a single-minded focus on violent vengeance. Any analysis would be remiss to ignore that a) the serial was written in 1968, and Portis would undoubtedly be aware of the second-wave feminist movement and b) the 2010 film was written, directed, and produced by the Coen Brothers, who know how to do subtle development of nuanced characters and big-picture themes. The original 1969 film is less profitable for analysis. In their hurry to cash in on the popularity of the novel and John Wayne, the studio focused on the Rooster character. Mattie (referred to as a “tomboy” by promotional materials of the time) exists as a novelty and a variation on the damsel in distress.

While the 2010 film does pass the Bechdel Test on the slightest of technicalities, no one is going to confuse it with Melancholia. The plot of True Grit is an interesting variation of the Women in Fridges meme because the roles are a reversal of the usual young female victim and older male protagonist structure. In this way Mattie is much more of a Dark Knight than a Marvelous fighting fuck toy. The overarching patriarchal heterosexist concern is obvious: neither children nor women are allowed to crave bloody vengeance. Vengeance is a privilege reserved for good-but-violent men whose women-property are raped or destroyed.

Mattie wears dark, loose, practical clothing. She climbs trees and carries weapons. She shows utter disdain for male privilege or La Boeuf’s pervy allusions to sexual contact. She has no interest in the older men for romance or protection. She is only concerned with their usefulness to her task, and she uses her will and her reasoning rather than seduction to convince them. Steinfeld’s Mattie emanates competence and confidence.

While many in the blogosphere were quick to use Mattie’s stoicism, blood lust, and independence as examples of why True Grit should be considered a feminist movie, others, such as Anita Sarkeesian at Feminist Frequency, have remarked that those same attributes argue against that designation. Rather, the adoption of these characteristics by a female protagonist constitutes an enshrinement of male privilege and traditional action-movie-masculine vales rather than an assertion of feminist values. By contrast, a feminist True Grit would emphasize cooperation, empathy, and non-violent conflict resolution. Without delving into the deeper arguments raised by this argument (e.g., what exactly are feminist values and are they necessarily exclusive of all traditionally masculine values), I can say that my initial reaction was to agree with Sarkeesian. Too often we see action movies that “counterbalance” a “masculine” (and usually secondary) female character by either putting her in a skin-tight suit, giving her a fatal personality flaw, or by implying that she is worthy of death for her perceived masculinity (I’m looking at you, Kick-Ass 2).

However, after some reflection I tend to agree more with Amanda Marcotte’s argument that True Grit should not be analyzed in the same way as more typical westerns or action movies. The subtleties in the source material and in the Coen Brothers’ delivery lend themselves to deeper interpretation. True Grit comments on many things: the unfair treatment of Native Americans (the hanging scene); the corruption of justice in our legal system (the courtroom scene); and the fact that there is often very little space between the “bad” and the “good” in this world (Chaney’s dialogue with Mattie at the creek and mine; Ned’s dialogue with Rooster).

As Marcotte points out, to understand the commentary on the development of Mattie as a young woman, we must look to the ending. Marcotte notes the shared symbology of Rooster’s missing eye and (adult) Mattie’s missing arm. By engaging in violence and by accepting the traditionally masculine values of vengeance, both Mattie and Rooster literally and figuratively lost part of themselves. As viewers, we are left to wonder: did Mattie’s consumption by vengeance as a young woman rob her of spiritual wholeness in adulthood? Does the adult Mattie feel that she was wrong to pursue vengeance? I do disagree with Marcotte’s assertion that True Grit is a feminist movie because the bleakness of the ending serves as an ultimate repudiation of traditional action-movie-masculine values. Instead, I see the ending as commentary on the infectious, long-lasting, and ultimately detrimental nature of violence as a human trait. Consequently, I conclude that while Mattie Ross may be considered a feminist character (loosely) True Grit is neither a feminist movie nor a movie that reinforces the patriarchal heterosexist narrative. It is a human condition movie, and one worth watching.

As for Hallie Steinfeld, she’s been getting work, and recently played Petra Arkanin in the film adaption of Ender’s Game. I’d like to see it, but damn you Orson Scott Card!

Andé Morgan’s perspective stems from a life spent always on the boundary: white and black, rich and poor, masculine and feminine. She takes shelter under the transgender umbrella.