|

| Saber Sharifi trains women boxers in The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

This is a guest post by Rachael Johnson.

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Saber Sharifi trains women boxers in The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

This is a guest post by Rachael Johnson.

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

|

| Image from The Boxing Girls of Kabul |

The Life of Million Dollar Babies (aka Golden Gloves), 2007. Directed by Leyla Leidecker

The Life of Million Dollar Babies (aka Golden Gloves), 2007. Directed by Leyla Leidecker

The Golden Gloves competition is the most storied amateur boxing tournament in the U.S. More than any other sport, however, boxing has been a true boys’ club, and an unspoken tradition barred females from entering since its inception in the 1920s. A new round of equality began in the mid-90s when a streetwise Brooklyn female pugilist named Dee Hamaguchi joined forces with the ACLU and pried the door of bias ever-so-slightly open.

Through a narrative pattern we often see in sports docs, we follow eight hopefuls striving for their personal bests as they keep their eyes on the prize of the 2005 finals in Madison Square Garden.

The Life of Million Dollar Babies is a powerful window upon the friction athletes often face not only on the field of gender, but also race and class. While male boxers are funded by the USA Boxing League, a technicality disqualifies females from financial support. When we witness the winner of the climactic quarter finals, a brassy Puerto Rican unable to go on to the finals simply because she can’t pay for it, we can’t help but feel the sting of social inequality.

The Heart of the Game, 2005. Directed by Ward Serrill

The Heart of the Game, 2005. Directed by Ward Serrill

Perhaps a female-oriented cousin of the classic documentary Hoop Dreams, The Heart of the Game is at its core about the inspiring, unlikely relationship between African-American basketball player Darnellia Russell and tax lawyer-turned-coach Bill Rensler.

Russell’s remarkable journey begins with her struggle for identity at an almost exclusively white, privileged high school, plunges into her unexpected motherhood and the complications of being a teen mom and athlete, and climaxes with her graduation from high school and garnering of her region’s Player of the Year Award.

A movie as much about growing up as about sports, this gem will uplift anyone with a heart … and with its shoestring budget of $11,000, it’s a testament to the possibilities of independent filmmaking.

Unmatched, 2010. Directed by Nancy Stern Winters and Lisa Lax

Unmatched, 2010. Directed by Nancy Stern Winters and Lisa Lax

A standout episode of ESPN’s ongoing 30 for 30 documentary series, Unmatched is a deftly-edited wealth of candid interviews that plays out like an epic clash of the titans. From their inauspicious entrance onto the women’s tennis scene in the early 1970s to their elevation to sports icons, Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova are bared to the audience in an intimate portrait of ardent competition and mounting admiration that matures across a span of over 80 fiery matches.

As a nuanced essay on the complex relationships obtained through time-ripened sports rivalries, this feature is truly “unmatched,” and along the way sketches the seismic shifts that have defined women’s tennis throughout the decades.

Training Rules, 2009. Directed by Dee Mosbacher and Fawn Yacker

Training Rules, 2009. Directed by Dee Mosbacher and Fawn Yacker

Subtitled “No Drinking, No Drugs, No Lesbians,” the short, bittersweet Training Rules is an expose of another front on which female athletes face prejudice: discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Made as a political consciousness-raiser by a lesbian activist and a psychiatrist, Training Rules brings to light the paranoiac witch-hunting atmosphere that pervades Penn State’s women’s basketball team. (In light of the notorious sex abuse scandal that rocked that school’s football team, the film is a doubly potent indictment of hypocrisy and double standards.) By focusing on the especially tragic case of Jennifer Harris, a promising hoop-star whose career was crushed by bigotry, Training Rules makes the pain of discrimination personal and impossible to ignore.

Dare to Dream: The Story of the U.S. Women’s Soccer Team, 2005. Directed by Ouisie Shapiro

Dare to Dream: The Story of the U.S. Women’s Soccer Team, 2005. Directed by Ouisie Shapiro

As with several of the docs already mentioned, Dare to Dream is not just about the struggle of individuals’ struggles for acceptance but also the grueling journey toward legitimacy within a particular sport. Over the course of the film’s duration, we get to know pioneering players Brandi Chastain, Mia Hamm, Julie Foudy, and Joy Fawcett, as well as the sweat and devotion they invested into making a once laughed-at franchise an Olympic spectacle.

All of these films are as packed with joy and pain as any glossy Hollywood product, and through the passions of their filmmakers, convey a sense of humanity few fiction flicks can compete with. By taking us through the lows as well as the highs, the crushing defeats as well as the delirious triumphs, these films inspire us by capturing the ineffable richness of sports and even life itself.

|

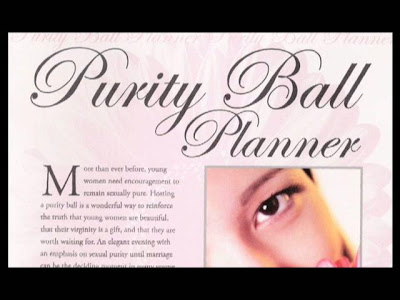

| How to Lose Your Virginity poignantly points out that in our culture, if you are a woman and have sex, you’re doomed, and if you don’t have sex, there’s something wrong with you. |

My favorite part of this film is that it is upbeat from start to finish. There’s no anger, there’s no judgment. I don’t want to riff on the “angry feminist” stereotype, but I know I tend to get pretty worked up and, well, angry when I talk about our culture’s toxic obsession with female sexuality and expectations of virginity. Shechter’s ability to teach, dismantle, expose and explore is remarkable. The audience is left with newfound knowledge with which they can criticize myths of virginity in our culture. However, the audience is also left with respect for everyone’s stories–those who are remaining virgins (no matter their personal definition), those who don’t and those who have no idea what it all even means. When a documentary can do that, it succeeds in a big way.

|

|

The phrase “purity balls” will never not make me giggle.

|

Throughout How to Lose Your Virginity, Shechter establishes common ground and values every individual’s experience, criticizing only the cultural myths that make us feel fear and shame about our sexuality. Even when she tackles pornography and purity balls, she does so with respect and cultural criticism, not disdain.

|

| The Grey Area: Feminism Behind Bars promotional still. |

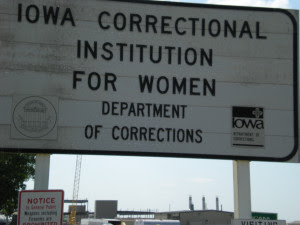

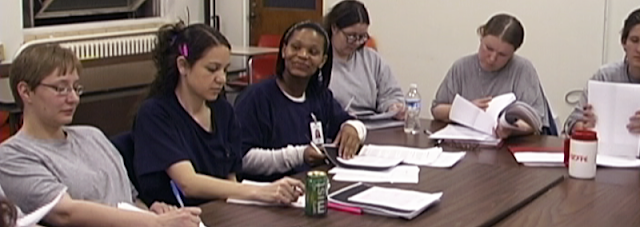

“I wanted to make a documentary about my experience there because I had a feeling that teaching a feminism class at the women’s prison would be a good framework to talk about women’s issues in the criminal justice system in general and to bring the stories of these women to the public through this film.”

|

| The documentary was filmed at the Iowa Correctional Institute for Women. |

|

| These women’s stories were highlighted throughout the documentary. |

|

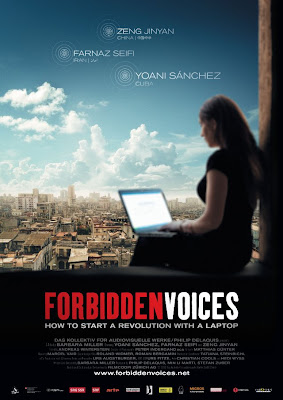

| Forbidden Voices movie poster. |

Written by Leigh Kolb

|

| Yoani Sanchez |

|

| Farnaz Seifi |

|

| Zeng Jinyan |

Forbidden Voices is a selection from Women Make Movies, an organization that “facilitates the production, promotion, distribution and exhibition of independent films and videotapes by and about women.”

|

| Salmai movie poster. |

Written by Leigh Kolb

|

| Salma, a Tamil poet and politician. |

|

| Salma still must confront resistance from her family and the next generation. |

|

| 20 Something Documentary Poster |

Written by Amanda Rodriguez

The documentary 20 Something is a labor of love for its creator Lanze Spears.With a non-existent budget while sleeping on floors as he filmed, Spears followed and actualized his dream, which is exactly what 20 Something is about.

|

| A Girl and A Gun movie poster |

|

| “You move through the world as a target when you are female.” – Blue Violet |

|

| “People ask me how I came to own a handgun. I tell them because I have felt the fear.” – Robin Natanel |

|

| Scotsdale Gun Club ad playing upon and, perhaps, exacerbating the female fear of attack in the public sphere. |

|

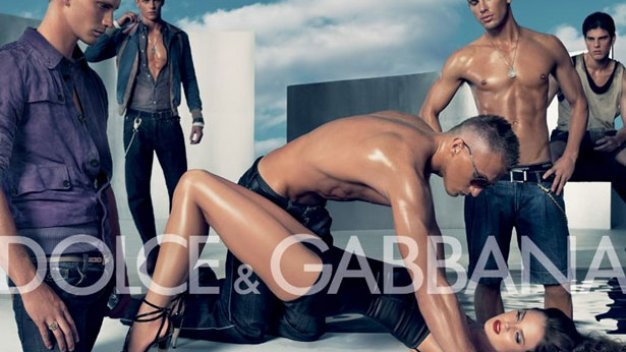

| I find this ad (for gang-rape) offensive, and it certainly triggers me. |

|

| Don’t tell me that’s not a phallus. |

|

| Movie poster for Stories We Tell |

So, how do we define “real” anymore or, for that matter, what is “true”?

|

| Polley and her father in Stories We Tell |

Mary Jo Murphy gives some background on the film in her New York Times review:

A bit more about “the story”: Ms. Polley is the youngest of five siblings. Dad was an English actor in Toronto; Mom, an actress, had two children from a marriage before she met him. She died of cancer when Sarah was 11, and at some point after that, one or more of her much older siblings began to tease her about her paternity. Eventually she did a little investigating.

When she found her answer, and talked to her father and siblings about it, she became fascinated with how each of them was “telling the story and embellishing the story and making the story their own.” The act of telling the story, she said, “was changing the story itself.”

|

| Polley’s father in Stories We Tell |

Polley is making a film about her father, her late mother, her siblings. She should protect them. What she shouldn’t do is offer up the resulting feel-good whitewash to the scrutiny of a watching world. She shouldn’t force on strangers the task of sitting through this. And she shouldn’t present a work of vanity and closed-in narcissism as an exercise in soul baring, because it’s embarrassing for everybody.

|

| Polley’s mother and father in Stories We Tell |

Leigh Kolb wrote a piece for Bitch Flicks last November called, “Female Literacy as a Historical Framework for Hollywood Misogyny” in which she suggested that, “When women finally break through and are able to tell their stories, those stories are immediately dismissed as silly and trivial.” She goes on to say:

Perhaps this bleak, largely anti-feminist landscape in Hollywood is more deliberate. If we acknowledge women’s long history of being neglected education and literacy, and that women have been repeatedly told (or observed) that their stories lack action and intrigue for a broad audience, how can this not have larger social effects? And at some point, do we come to the conclusion that these messages are what the dominant group wants?

|

| Polley’s mother in Stories We Tell |

|

| Sarah Polley, badass |

|

| Anne Braden: Southern Patriot (2012) |

She wanted a different world.

|

| Anne Braden |

Award-winning filmmakers Anne Lewis and Mimi Pickering created this first-person documentary, and its brilliance rests greatly on the fact that Braden herself and her contemporaries, biographer and mentees tell the story. The seemingly hands-off approach by the filmmakers (no audible interview questions or voiceovers) works incredibly well, and lets Braden’s remarkable legacy unfold on its own merits. The soundtrack is appropriately present, but not noticeably so, as it should be in a documentary.

This documentary, in short, is amazing. Aside from the technical success of the film is the fact that Braden herself was an extraordinary human being.

Braden says that when she had the realization that something was wrong, it was like photography: “You put the film in the developing fluid and it begins to come clear, but it’s been there all along.”

The images kept becoming clearer and clearer to Braden as she worked as a journalist in the south and covered the courthouse, seeing black men be imprisoned for looking at white women the wrong way, and seeing how murdered black people were not newsworthy.

She didn’t feel guilt. She felt motivated to change her world.

Early on in her career, Braden recognized that issues of class and race were inextricably linked. She says,

“I was in a prison and life builds prisons around people and I had the prison that I was born white in a racist society. I was born privileged in a classist society. The hardest thing was class. I don’t know that I could have ever broken out of what I call the race prison if I hadn’t dealt with class.”

She married Carl Braden, who was a “radical” activist active in the labor movement. “We got married to work together,” she says. By 1951, Braden was combining marriage, motherhood and activism.

Early on, her activism focused mainly on writing for and talking to black audiences about white people’s roles in racism and classism. The head of the Civil Rights Congress, William Patterson, told her that black people already know what she’s telling them–she needed to talk to white people, because they are the problem. She remembers that he said to her, “You know you do have a choice. You don’t have to be a part of the world of the lynchers. You can join the other America–the people who struggled against slavery, the people who railed against slavery, the white people who supported them, the people who all through Reconstruction struggled.” She says, “I was very young, and that’s what I needed to hear.” Her work began in earnest.

The Bradens bought a house for a young black family, the Wades, in an all-white neighborhood (it was a way around segregation–Andrew Wade gave them the down payment, the Bradens purchased it, and then transfered the deed). The Wades’ home was shot at, crosses were burned in the yard and a bomb was set off underneath their daughter’s window (remarkably no one was physically hurt).

|

| The Wades, showing where rocks had been thrown and broken the windows of their home. |

The bomber was never caught or tried, but the Bradens were, along with five other whites who helped defend the Wades’ house. They were charged with sedition–it was, prosecutors said, all a plot by communists to overthrow Kentucky and the nation.

Braden says that “If you use every attack as a platform, they can’t win and you can’t lose. It works like a charm.” They used their arrest and jail time as a platform. “You can’t kill an idea anyway,” she says. “To a segregationist, integration means communism.”

The film highlights footage from Ku Klux Klan rallies, newspaper stories, meetings, marches, beatings and shootings during the red scare and the civil rights movement. The footage–often presented without narration–is powerful and provides the visual, historical context to Braden’s stories.

The film moves forward through each decade, highlighting social justice struggles (especially regarding race and economic injustice) and Braden’s continuous role. The complexity of anti-communist sentiment, the freedom of speech and association and violence of the ongoing civil rights struggles are examined in depth.

It was difficult watching the momentous struggles and changes of the 60s make way into the 70s, when she says, “That sense of being part of something larger gets lost.” Political activists were repressed and imprisoned, and much of the momentum was lost.

|

| Anne Braden |

As the footage from the 70s surfaces, it’s in color; all of a sudden history doesn’t seem so far away. When white women are screaming and chanting about “Niggers” when busing was implemented in 1975, and throwing rocks at the buses, it’s jarring how close it all is. David Duke screams about white power. Communist workers at an anti-Klan rally are shot and killed in the late 70s.

In a statement that seems all-too true today, Braden says of the lasting legacy of this era:

“And this idea of reverse discrimination took hold of the country, and I think it’s the most dangerous idea that’s ever been inflicted on this country. It tells white people that the source of their problem is people of color and it’s such a damn lie because it’s based on the theory that what black people got took something away from white people, and that is the opposite of what happened, every piece of legislation everything that happened that the black movement won, helped most white people and certainly poor and working class white people.”

At a 1980 rally in response to the communist workers’ deaths, she said,

“The real danger today comes from the people in high places, from the halls of congress to the board rooms of our big corporations, who are telling the white people that if their taxes are eating up their paychecks, it’s not because of our bloated military budget, but because of government programs that benefit black people; those people in high places who are telling white people that if young whites are unemployed it’s because blacks are getting all the jobs. Our problem is the people in power who are creating a scape goat mentality. That, that is what is creating the climate in which the Klan can grow in this country and that is what is creating the danger of a fascist movement in the 1980s in America.”

As the film progresses, we see Braden marching for economic justice and to end police brutality. She stands out, with her cropped gray hair, small body and denim jumpers. Her voice shakes into a megaphone when she speaks at rallies, but her age doesn’t stop her. She keeps marching. When she can’t march, she’s pushed in a wheelchair.

Braden passed away in 2006 at age 81. Right before she died, she said, “I just don’t have time.” She still felt she had too much to do.

|

| Anne Braden and Cornel West |

I don’t know that I’ve ever been so inspired by a documentary. By the end, I was crying, near-sobbing–in celebration of Braden’s life, in mourning her death and in feeling a burning fire in my white belly that I needed to do something in this world. Anne Braden had effectively told me that I needed to get to work.

At a march, Braden says, “We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it’s won.” It hasn’t been, and we must continue her legacy.

Anne Braden: Southern Patriot puts Braden’s lifelong activism into the developing fluid and makes it clear to all of us. We should all look carefully at these images and be moved to not just frame them for display, but to make them shape our world now.

|

| Wadley from Haiti |

|

| Mariama from Sierra Leone |

Connecting the nine stories are interludes which show other girls in school uniforms as they hold us up signs sharing dreary statistics about girls in the developing world, such as boys outnumber girls in primary schools by 33 million. The stories teach the audience that these girls live in families that love them—even if that love looks different than it does in “the West”—and that education, poetry, art, and organizing are the keys to giving each girl the tools to recognize her own importance and to find her voice.

|

| One of the interludes. |

Girl Rising knows and plays to its audience: women in “the West” with access to basic services and education who have some extra money in the bank and a desire to help other women. The documentary works to connect audience members to a movement with the lofty goal of raising money to ensure more girls are educated worldwide.

|

| Amina |

Here’s my concern: I don’t think any of these problems will go away if she rejects and sheds her burqa. So when (spoiler alert) veiled girls start to run up the hill tearing off their burqas as the music crescendos and the voiceover offers us the idea that liberation is just around the corner once the girls reveal their identities, I cringe. This gesture is a bravery manufactured for the audience. Taking off a burqa is a solution that makes the audience feel good. It echoes the rhetoric of post-9/11 warmongering when suddenly we needed to invade countries in the name of women who needed liberation, a convenient excuse when those same women’s plights were completely ignored up until September 10, 2001. Of course, the movie does this on purpose, allowing us to feel justified all over again in our simultaneous invasion and ignorance.

|

| An advertisement for Good Hair. |

|

| A six-year-old girl gets her second perm in Good Hair as Chris Rock watches. |

|

| Her definition of good hair- “something that looks relaxed and nice.” |

|

| Tracie Thoms discussing why she loves being natural. |

|

| Chris Rock talking to scandalously clad women about hair. |