—–

Tag: Comedy

Animated Children’s Films: Anthropomorphism and Sexism in Disney’s The Aristocats*

Animated Children’s Films: From the Archive: Fantastic Mr. Fox

Note to Wes: if your one female character (wife + mother) is supposed to be a professional artist, could you at least show her working during the DAY in her STUDIO, not cooking all day and painting outside at night with her kid and husband sitting around her?It’s disappointing that this film incorporates Dahl’s lack of interest in women (that veers close to misogyny). I guess it’s not that much different from other Wes Anderson films that way…but with a little more imagination it could have been so much better.

1) In the original, Mrs. Fox was complicit all along. 2) Mr. Fox never went on the wagon. 3) Mr. and Mrs. Fox had four cubs, not one little nutcase, and Dahl made no mention of a yoga-bending super-nephew. 4) I’m pretty sure the point of the story wasn’t Mr. Fox’s flagging self-esteem or his strained relationship with his son. But this is cinema in the time of Oprah, when Reductio ad navelgazing is the inevitable narrative arc.

Animated Children’s Films: Lilo & Stitch

This is a guest review by Sarah Kaplan.

|

| The Grand Councilwoman |

|

| Jumba and Pleakley |

|

| Lilo |

Life isn’t easy for Lilo, whose parents are dead, leaving her sister as her legal guardian. Lilo describes her family as “broken,” and it’s clearly a difficult situation for both sisters. Lilo is aware that her family isn’t normal, but she still considers the concept of “ohana,” family, very important. It’s a central theme in the movie.

Lilo also faces the cruelty of female cliques, despite her young age. In the scene pictured in the screenshot above, other girls her age refuse to play dolls with her. (In a nice touch, the other girls’ dolls, while Barbie-shaped, match their different hair colors. Two of these girls, like Lilo, are native Hawaiians.) To be fair, she had bitten one of them not long before. This movie doesn’t whitewash its protagonists, and it isn’t afraid to show children as cruel and violent at times.

|

| Nani |

Lilo & Stitch is a wonderful, thoroughly feminist children’s movie, and one of my personal favorite movies of all time. It’s funny, thoughtful, and a surprising treat from Disney.

—–

Animated Children’s Films: Is Smurfette Giving it Away? Let Your Kids Decide

Animated Children’s Films: Megamind: A Damsel Who Can Hold Her Own

|

| Megamind (2010) |

|

| Roxanne Ritchi, voiced by Tina Fey |

|

| Hal and Roxanne |

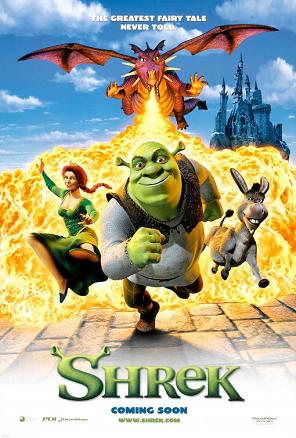

Animated Children’s Films: Onions have Layers, Ogres have Layers – A Feminist Analysis of Shrek

|

| Shrek (2001) |

|

| Artwork by William Steig |

|

| Fiona, imagined by Dreamworks |

Animated Children’s Films: ‘How to Train Your Dragon’

There is plenty to enjoy about How to Train your Dragon. The animation is lovely, the story is energetic, and the landscape feels fresh and inviting. The film also contains a number of plot elements that are far too common in children’s films these days.

|

| How to Train Your Dragon (2010) |

The film doesn’t make much use of its female characters. Hiccup’s mother is dead like many mothers in animated films geared towards children. Her only purpose is to provide the male protagonist with some sort of emotional complexity. There is a female elder who picks which student slays a ceremonial dragon but she is only in the film for a few seconds and she has no dialogue. The most prominent female character is a young Viking hotshot named Astrid. She is the star pupil in dragon training who is tough as nails and always on edge. If this character seems familiar it’s because she is. She’s Colette from Ratatouille, Eve from Wall-E, and Tigress from Kung Fu Panda. She is the latest in a long string of female characters that are tough and talented but second in importance to the males. Perhaps the most iconic example of this trend for our current generation would be Hermione from Harry Potter. She’s the brains but not the hero.

|

|

|

|

There are a number of other problems with female sidekicks of the types that I have just listed. One is that they are only skilled when it comes to playing by the rules. Characters like Astrid and Tigress are shown as being obsessed with following instructions. They work hard to receive approval from their teachers both of whom are male. Likewise Colette told Linguini that it was their job to “follow the recipe.” Female characters like this are shown operating specifically within the boundaries that have been laid out for them by male superiors. They are not shown to have the insight to break rules and challenge the system the way the male protagonists do. Another problem with these types of female sidekicks is that while they are very talented they often don’t possess the talents that the stories they exist in value. Take Hermione for example. While she is incredibly smart, the story she exists in only treats intelligence as second in importance to bravery, which is what Harry embodies. With How to Train Your Dragon, it’s the same problem. Astrid is strong-willed, physically powerful, and full of fighting spirit, but this is not what is valued in a story that ultimately preaches gentleness and a sense of compassion, which is what Hiccup represents.

The film’s final setback is that it boasts antiwar and antiracism credentials that it doesn’t live up to. While it is true that Hiccup is presented as the symbol of peace between humans and dragons, the story also uses a battle as its climax. Hiccup and Toothless have to save everyone by defeating a giant dragon in combat in a sequence that is clearly set up for audience suspense and enjoyment. Even more troubling is the relationship between the humans and the dragons at the end of the film. While they may be at peace the dragons have become Viking pets. It is a peace that is built on a hierarchy and it makes the film’s message very disturbing if the dragons are to be viewed as a metaphor for another race of people. This movie wants to have it both ways. On the one hand it uses the dragons to tell a story about different races rising above war. On the other hand it portrays the dragons as less intelligent pets because the audience will find this amusing and empowering. The title of this movie is not How to Coexist with a Dragon.

How to Train Your Dragon is an attractive and at times enjoyable movie, but in the end its problems outweigh its charms. The characters are too simplistic, the plots are too familiar, and the politics are too compromised. If a film is going to teach politics to children (or adults for that matter), the film should challenge them, not cater to them.

Guest Writer Wednesday: Why Watch Romantic Comedies?

|

| some romantic comedies |

This guest post by Lady T previously appeared at her blog The Funny Feminist.

I also think that looking at romantic comedies is a worthwhile feminist project. I want to look at how men and women are represented in these films. I want to look at the way romantic expectations are presented in our popular culture. I want to look at issues of consent. I want to look at the way the comedy genre affects the romance genre and vice-versa.

For the parody or spoof film genre, the entry lists three examples. 0 of 3 of these examples have female protagonists.

For the anarchic comedy film genre, the entry lists two examples. 0 of 2 of these examples have female protagonists.

For the black comedy film genre, the entry lists fourteen examples. 1 of these 14 examples (Heathers) has a female protagonist without a male co-protagonist, and fewer than half have a female co-protagonist.

I think you can all start to see the pattern here, but let me continue just to belabor the point.

Action comedy films. 9 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Comedy horror films. 9 examples, 1 female protagonist (in Scary Movie).

Fantasy comedy films. 6 examples, 2 female co-protagonists (The Princess Bride, Being John Malkovich), 0 female protagonists without male co-protagonists.

Black comedy films. 3 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Sci-fi comedy films. 8 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Military comedy films. 9 examples, 1 female protagonist (Private Benjamin).

Stoner films. 4 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Some might argue with me on particular examples, but it’s obvious that dominant characters in comedy films are overwhelmingly male. (I also understand that Wikipedia is not an entirely accurate source of information, but the examples that are used to represent these different genres explains a lot about our cultural attitudes.)

If you look at the entry on romantic comedies, you see many more films that have female protagonists, or at least female co-protagonists. Especially significant is the list of top-grossing romantic comedies. 22 films are listed. More than half of them have female co-protagonists, some have one female protagonist, and one has (gasp!) more than one female protagonist (Sex and the City).

—-

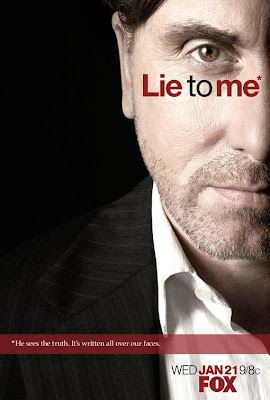

Some Scattered Thoughts on Detective Shows and Geniuses

After an episode of Monk, I spend some time with Cal Lightman from Lie to Me, a current show in its third or fourth season that centers around an agency called, The Lightman Group, which specializes in reading facial expressions. Apparently, we all have these things called “micro-expressions” that betray us when we’re lying, but only highly-trained people can catch and decode these micro-expressions, (e.g. the employees at The Lightman Group). Dr. Lightman is literally a human lie detector, and it’s fun to watch him get up in the faces of liars and act like a cocky British bad-ass. He, too, works with women who, while brilliant and talented in their own right, spend a significant amount of their screen-time playing sidekick to Lightman and cleaning up his messes.

All this boy drama started to become stifling, so I browsed Netlix and found Medium (which first aired in 2005), a show I’d seen a few episodes of—and liked—but that I never really pursued, probably because of my embarrassing fear of the occult. Medium centers around Allison DuBois, a woman who can communicate in various ways with the dead, and who also has some psychic ability, such as knowing when a person might die, or experiencing creepy flashes of the horrible shit people have done in their pasts. DuBois interests me because, in addition to holding a job as a consultant for the district attorney (similar to Monk’s role in some ways) she’s also a mother of three young girls and has a rocket scientist husband who gets fed up on a regular basis with her mind-reading, afterlife communing talents. He admires her crime-solving abilities but deep down wishes she’d continued to pursue her law degree instead, in the name of normalcy. In this show, the man slash husband plays sidekick.

These three detective characters are similar in that their main role on their respective television shows is to catch criminals. All three of them aid the police force. All three of them often endanger themselves in the process of tracking down criminals. All three of them always succeed (which is the formula for crime dramas), and we’re led to believe that the criminals wouldn’t have been caught without the help of these characters. Monk, for instance, even with all his quirks and the accommodations he requires, is hailed as an absolute genius by his colleagues and is constantly referred to as “the greatest detective in the world” by his assistant. And he is, in fact, a scary good detective, and it’s for that reason that his quirks and his often abusive behavior (while played for laughs) is forgiven—the audience is led to believe that Monk wouldn’t be a genius detective without these eccentricities. (An episode where Monk takes an antidepressant for his phobias and subsequently becomes useless as a detective confirms that theory.)

Cal Lightman, too, might be one of the most egotistical characters I’ve seen on television, and he’s immensely likeable. He breaks all the rules and consistently does pretty much the opposite of what anyone tells him to do. His lack of respect for authority often helps him win his cases; his immediate contempt for and suspicion of The People in Charge sends him in unusual directions to solve crimes, so the audience is treated to episodes where he (hilariously) and deliberately does things like checking himself into a mental hospital, or going undercover as a coalminer and threatening to blow up the place if he doesn’t get answers—but we, and his colleagues, respect him more for his unorthodox detective work. Yes, he may step all over the people around him, but that’s just how he does things; who are they to get in the way of a genius in his element? But Cal inevitably leaves some sort of mess behind when he operates outside the box (i.e. pisses off so many authority figures), and it’s no surprise that his colleague, Dr. Gillian Foster, a psychiatrist who partnered with him to start The Lightman Group, gets stuck making amends on his behalf. (I’m very much reminded of the Dr. House/Dr. Cuddy dynamic here from the television show House.)

Interestingly (or not), both Monk and Lightman find motivation and success in their careers because of dead women; Monk is literally obsessed with finding Trudy’s killer (which is the one crime he hasn’t been able to solve), and Lightman wasn’t able to save his mother from killing herself; he watches old video tapes of her, repeatedly pausing them to read and reread her micro-expressions. This “I’m avenging the death of my [insert relationship to woman here]” theme shows up in, like, every movie about a man who achieves anything. In these shows and movies, even the dead women exist as nothing more than plot points to drive the narrative forward. It’s sick and demeaning to women. In fact, I should make a list of the films and television shows in which this trope exists and call it the “I’m Avenging the Death of My [Insert Relationship to Woman Here] Trope.” (I’m doing it.)

Did you think I forgot about Mrs. Allison DuBois? I love her. And oh what a difference gender makes on a detective show. In her world, she’s successful not because she’s eccentric or because she has a god complex but because she has special powers. In her world, even though she solves case after case, and sheds new light on past cases, she must always fight to be taken seriously by her boss, by her family, and often by her husband. The audience watches DuBois struggle both with solving the cases (while trying to raise a family of young daughters and keep her marriage intact) and dealing with the way her job directly impacts her interpersonal interactions. She isn’t, as is the case with Monk and Lightman, surrounded by an endless network of supportive characters no matter what; instead, her kind of “genius” is scary and unnatural and not to be trusted.

I get it. Dead people tell her shit, which is a little different than being aided by obsessive-compulsive disorder and a lucky mixture of intelligence coupled with extreme arrogance and defiance. But DuBois must decode the messages she gets, too. A dead person doesn’t just show up and say, “Hey, that dude killed me, and my body’s buried behind that dude’s house over there. Find me. Thanks.” The occult is obviously way more complex than that (eek!). While Lightman and Monk find themselves surrounded by people who worship them, she deals with the extra struggle of convincing people she isn’t crazy—but like, how many cases does she have to solve before people just admit she’s fucking awesome?

Arguably, DuBois is a much more fleshed-out character than Lightman or Monk. She has a husband, a family, a career, unacceptable sleep patterns, daycare to deal with, a possible alcohol problem, parent-teacher conferences to deal with—a life! The men, though, just kind of do the same shit every episode. Lightman does, however, have a teenage daughter, and season two ends with him flipping out about his daughter losing her virginity. I’m not joking. That’s how the entire season ends—in an episode where Lightman gets upset about his daughter not being a virgin anymore. I’m serious. It’s called “Black and White,” and it’s a horrible episode. (Seriously.)

I’m at a bit of a disadvantage in discussing Medium because I’m only familiar with the first season. Perhaps things get better for Allison in later seasons. Perhaps the men in her life stop expressing so much condescension and distrust toward her and endow her with some Lightman- and/or Monk-esque respect. Perhaps she no longer feels compelled to apologize for her own idiosyncratic crime-solving abilities and develops Lightman’s uber-masculine arrogance about it. (But don’t take that confidence too far, Allison—no one wants to work with a bitch.) At the very least, in the first season of Medium, I sort of love her husband. I mean when is a male rocket scientist ever the sidekick, hmmm?

I guess ultimately what concerns me about these portrayals of male and female detectives is that it mirrors real life. Men are geniuses. It’s a fact. I think I once heard someone refer to Sylvia Plath as a genius in a lit class, but it’s absolutely uncommon to hear a woman referred to as such. Being a (male) genius comes with perks, too. You’re forgiven your bullshit, your weirdness, your unorthodox behavior, your screw-ups, your law breaking. I always think specifically of Roman Polanski—a film director who drugged and raped a 13-year-old girl, never went to prison, and managed to garner support from thousands in Hollywood who signed a petition on his behalf. He’s a genius! He’s paid his dues! Let him come back to the U.S.!!!!! I also recall the outrage surrounding the Julian Assange rape accusations—men across the globe immediately came to his defense (including “liberals” Michael Moore and Keith Olbermann), arguing: It’s a setup! Those women are lying! He’s a genius! Kneel before Zod!

Even though I really want to end this post on the phrase “Kneel before Zod!” I’d also like to say that while I love DuBois and think she is a genius and want to see her treated as such (in the same manner as her male counterparts) I’d also love to see more regular-ass women characters achieving genius-level shit. We need and love our women with superpowers (Buffy, too, of course), but I personally want to see a woman who looks like me, who does weird and unacceptable shit like me, who sometimes goes out in public wearing sweatpants like me, achieving some genius-level shit. I truly believe, as someone who studies pop culture and media, that we’re not going to make much progress toward ending misogyny in our everyday lives if we don’t deal with the misogyny we’re bombarded with in television shows, music videos, advertisements, films, and children’s programming. If we see it reflected all around us constantly, it becomes the norm. So, we need to call this shit out and keep calling it out, even when it seems like a tiny thing—like douchebag male detectives with unorthodox methods getting a free genius pass while brilliant female detectives with unorthodox methods have to endlessly prove their competence to significantly less competent people.

That right there is fucking patriarchy in action. Now:

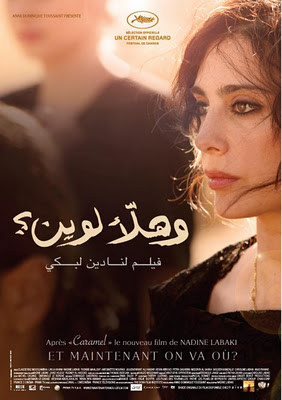

Guest Writer Wednesday: Where Do We Go Now?

|

| Arabic movie poster for Where Do We Go Now? |

—