|

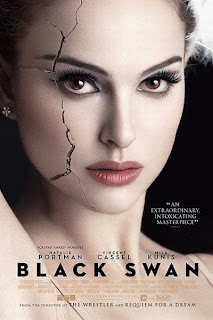

| Nina is cracking… |

Amber’s Take:

There’s a lot to say about Black Swan, and the more I think about it, the fewer definitive, and perhaps positive things I have to say. Before getting too ahead of myself, though, I must say that the performances–particularly Natalie Portman’s–were amazing, the dance sequences were compelling and seemed very well done, and the film was, overall, visually stunning. This is the most intensely visceral film I’ve seen in some time, and simply remembering certain moments still causes me to cringe. I loved the image of the goose flesh appearing on Nina Sayers’ (Portman’s) skin, as she began to physically embody her role as the Swan Queen, and the nod to Cronenberg’s The Fly when thick, black feathers began to sprout from Nina’s skin (as the hairs sprouted from Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle during his physical transformation into, well, a fly).

On a literal level, the film seems to be about the transformation of an artist–in this case, a dancer–into a role. It also is, very specifically, about the physical rigor of ballet, and the lengths an artist will go to in perfecting her performance. Ballet is a physically grueling art form that seems diametrically at odds with the female body. Like gymnasts, from what I understand, a ballet dancer must fight against a mature woman’s body, maintain an impossibly thin-yet-strong physique, and endure at times severe physical pain. On a more metaphoric level, this is what society expects all women to endure, though I don’t think we can read the white swan/black swan as a direct metaphor of the virgin/whore dichotomy or expectation for women in our culture. There are several other things going on in the film, one of the most problematic being (s)mother love.

What on Earth is Barbara Hershey’s character doing in this film? In a near-deranged, over-the-top role, we see a woman who couldn’t make it out of the corps during her own ballet career, and who blames her daughter for the unhappy end to that career. Erica Sayers infantalizes her daughter, dominates her life, pummels her with guilt for under-appreciating her (the cake scene, anyone?), and generally serves as the movie’s biggest villain–worse than an artistic director who sexually assaults and torments Nina. Oh, that’s nothing compared to Mommy Dearest. So what do we make of Nina’s mother–and why was she even in this movie?

Stephanie’s Take:

While I share some of your concerns with (s)mother love, and Barbara Hershey’s character in general, I really enjoyed the film. So before I respond to some of the issues you mention, let me say what I liked so much about Black Swan:

First, a fairly obvious but no less interesting way to read the film is as an indictment of prescribed femininity. Nina’s entire existence is wrapped up in an attempt to be perfect, whether it’s striving to be the perfect ballerina or the perfect daughter. We see what her breakfast looks like, grapefruit and a hardboiled egg (if I remember correctly), and as you mention, the struggle to maintain a child’s body resonates throughout. While that may be particularly important for careers in ballet and gymnastics, it’s also our society’s ideal body type for all women, so I very much like that Black Swan delves into (however metaphorically) the potential consequences of restrictive and unattainable “perfection” in women.

When Nina can’t live up to the casting director’s Perfect Ballerina or her mother’s Perfect Daughter, she basically loses her shit. Thomas (the casting director, played by Vincent Cassel) wants her to embrace her sexuality, to seduce the audience with it (channeling the Black Swan). Erica (her mother) wants her to remain childlike and innocent (channeling the White Swan), and both Thomas and Erica represent the double-edged sword that all women face: be sexy, but not slutty; be sweet, but not a total prude. In the words of Usher, “We want a lady in the street but a freak in the bed.”)

When Nina can’t fulfill both these roles simultaneously, as much as she tries, the film shows us her breakdown: her body betrays her in literal ways, with bleeding toes and scratch marks that suggest self-mutilation (another hallmark characteristic of young women struggling to cope with similar stress); and her body betrays her in ways that suggest hallucinations: pulling “feathers” from her flesh, or ripping off her cuticles, only to discover moments later that her hand is fine. I found that part of the film, the hallucinatory transformation into the Black Swan, super interesting because it seems to happen to her accidentally—as she experiences the transformation, she doesn’t understand what’s happening, and it frightens her.

In fact, I would argue that her body isn’t her own at any time during the film. Thomas wants to control her body in a sexual way, often groping her and kissing her against her will. And when Nina attempts to explore her sexuality, to take ownership of it through masturbation, she suddenly realizes her mother is in the room (to the gasps and laughter of audiences nationwide), and she buries herself under her covers like a child. Erica constantly explores Nina’s body either by looking at her or physically touching her, often insisting that she remove her clothes—creating an inappropriateness in their relationship that I don’t quite know what to do with.

Regardless, I like that Black Swan implies that these ideals for women can’t actually exist without women destroying themselves in the process of attaining them. We live in a society where women’s bodies exist as pleasure-objects for men, as dismembered parts to sell products, as images to be dissected, airbrushed, made fun of, all under a government that continues to chip away at women’s rights to bodily autonomy. In that kind of environment, when does a woman’s body ever feel entirely her own? Black Swan sets up that metaphor quite well, asking the viewer to experience Nina’s struggle to live up to society’s ridiculous expectations for women through several cringe-worthy moments.

That rocks. But I wonder if that effort gets trumped by some of the more objectifying scenes, like the “lesbian sex scene” and the masturbation scene. Is it possible to comment on society’s expectations of women and beauty without also objectifying women in the process? Does Aronofsky linger a little too long at times? And, in response to your second paragraph, why can’t we read the Black Swan/White Swan as a direct metaphor for the virgin/whore dichotomy? (Oh, and yeah, I’ll throw it back to you—what the hell is happening with Nina and her mom?)

Amber’s Take:

You make a lovely and convincing reading of the film as an exploration of the impossibility of society’s contemporary take on womanhood. I think my resistance to this reading—or, more specifically, my dissatisfaction of this being the ultimate reading—has everything to do with Erica Sayers, though neither of us is certain how to exactly read her character. More on that in a moment (ha ha). Though meaning doesn’t end (or begin, necessarily) with a director’s intention, I also think this reading gives Aronofsky too much credit; in other words, I don’t know that the film is that good—that altrustic, that interested in women’s experience—or that cohesive.

Aronofsky has a clear interest in the limits of the human body. While watching Black Swan, I thought about his previous movie, The Wrestler, and the ways in which that solitary person pushes his body to limits most us of (those of us who aren’t professional wrestlers or ballerinas) find absurd and painful to even see. We could extend our conversation indefinitely by bringing in other movies as objects of comparison (The Red Shoes

), but I do see some structural similarities between Black Swan and The Wrestler that warrant at least a cursory comparison–and I’m sure others have done this comparative work in reviews around the web.

An important question to ask when we’re trying to figure out Black Swan is this: How do we see Nina Sayers at the end of the film? Is she a victim of her society/mother/creative director? Or is she victorious, in that she conquered the perceived limits of her body to achieve her own stated goal: to be perfect in her Swan Lake performance. (Did we see the protagonist of The Wrestler as victorious or defeated in his final leap?) Nina masters her performance, nailing the Black Swan to the point she imagines her arms transforming into wings. This was the most thrilling sequence in the film—her performance was beautiful, and much more impressive than any of the other dance sequences. Is the Black Swan a villain? In the ballet, yes, and the White Swan is the tragic heroine. Films generally tend to do a better job of making the villain more compelling than the hero, but if both roles are (metaphoric) unattainable goals, how do we read those final moments?

It’s not that I disagree with your reading—I really want that to be what the movie is ultimately about, but there are too many half-baked ideas competing with each other to allow me to say Okay, it’s about X. And, frankly, there’s an awful lot of pleasure to be had by gazing at tormented bodies in the film for me to wholly believe its feminist message. Before Nina gets the lead role in Swan Lake she looks hopefully at a woman walking toward her at a distance, and sees herself in the face of a stranger. So, she’s looking for her a reflection of herself, evidence of her own existence in other people. I don’t think this is a statement about a woman’s unstable identity; I think it’s what an artistic performer does. And possibly a person grappling with mental illness. What about Lily (Mila Kunis)? Her cheeseburger, ecstasy, and alcohol-fueled night with Nina, leading to empowered club dancing (sarcasm), random dude-kissing, and imagined sexy lesbian action between the two, does…what, exactly? Neither the skeezy artistic director’s advice (masturbate!) nor San Francisco Lily’s trite transgressions work to sexually liberate Nina…or do they? At least they bring her into active conflict with her mother.

Now. Nina lives with a mother who is basically a lunatic. I mean, let’s just say it: Nina’s mother is fucking nuts. Why (in the world of the film) does Nina need to have a mother who is fucking nuts? Couldn’t she have been moderately nuts, like most of us, with contradictions, who acts in moderately selfish ways which can moderately mess up a daughter? That would’ve allowed the themes we’ve discussed to be played out just as intricately and interestingly. How does this character fit into the movie? Taken literally, Nina’s mother is at fault for her child’s problems. As mothers tend to be in films made by men, and as psychiatrists believed in the 1960s (I’m thinking of the concept of the schizophrenogenic mother here–the idea that an oppressive mother could actually cause schizophrenia in her children). While we might be seeing a version of Erica Sayers from Nina’s untrustworthy perspective, what good is it—even if it’s not an accurate representation—for Nina to see her mother this way? Taken metaphorically…what? There’s no feminist reading I can discern in a film that I want to be feminist.

Stephanie’s Take:

I completely agree that it might not be useful, or even possible in a film as complicated as Black Swan, to come up with a definitive reading. But I still believe so much is at stake with regards to women and identity and the fluidity of that identity, in a culture that forces women to possess multiple, often contradictory identities. Maybe I’m giving Aronofsky too much credit, but I disagree with your suggestion that Nina’s literal reflections aren’t a statement about a woman’s unstable identity.

Yes, this film comments plenty on the artist and how performance can impact an artist’s life, how the artist must take on certain traits to enhance her performance, and how that act might impact her life when she isn’t on stage. However, given the fact that we’re all “performing” our identities to an extent (like the prescribed gender roles we’re taught from birth to perform), it’s worth looking at how Nina, a character whose identity seems so wrapped up in the expectations of those around her, copes—or doesn’t cope—with the pressures of womanhood and what’s required of that particular role.

It’s impossible not to notice Nina’s reflection everywhere. She sees herself reflected in mirrors as she dances, or when she’s reading the word “whore” on the bathroom mirror of the dance studio, or when she sees her face in the subway car windows. And as you mentioned, she sees her face superimposed on the faces of strangers in public—and even in the mirror at her own house, where she and Lily’s faces are superimposed.

It happens again during the sex scene; Lily’s face becomes Nina’s own face at one point, and we can hear Lily creepily whispering the words of Nina’s mother, “my sweet girl” over and over. Since we learn later that this sex scene is most likely Nina’s hallucination (and I think there’s enough evidence to even make the argument that Lily’s entire existence is a hallucination), it’s useful in interpreting the film to think about why Nina sees Lily, hears her mother’s words, and even sees her own image during a sex scene.

All this swapping of voices and faces (identities, if you will, haha) lead me to read all these people, Erica, Beth (Winona Ryder), and Lily as facets and projections of Nina’s identity. Beth, Thomas’s first “little princess,” is the aging ballerina who gets replaced by Nina, the younger ballerina. Erica, her mother, is the ballerina who slept with her director, got pregnant, and had to end her dancing career as a result. And Lily is the ballerina who embodies everything Nina tries so desperately to find within herself. She’s a carefree, sexual woman who repeatedly threatens Nina’s role in the ballet. Both when Nina is late to rehearsal and when Nina is late to the show’s opening—Lily stands in the background, threatening to take Nina’s place.

Keeping that in mind, it’s interesting that Nina “murders” Lily; on one hand, Nina seeks to absorb Lily’s empowerment, but on the other, the only way she can ultimately accomplish that is by killing it. Since murder is a pretty empowered act, I guess I get that. In fact, I think I liked it. Because Nina basically says Fuck You to the idea that Lily, who represents Nina’s unattainable sexual identity, is separate from herself, her whole self. In that moment, Nina transforms fully into The Black Swan, allowing Lily’s metaphoric death to push Nina to do what she previously thought herself incapable of accomplishing.

You argue that the alcohol-fueled, “imagined sexy lesbian action between the two” does nothing to really sexually liberate Nina. I struggled with this scene in the film probably more than any other scene because it feels exploitative and objectifying in the same way most Hollywood faux-lesbian sex scenes do. But I also believe it’s important to pay attention to all the stuff I mentioned previously. There’s tons of identity-shifting in this scene. Nina’s eventual sexual liberation (if we equate her successful transformation into the Black Swan with sexual liberation) begins here; when identities become interchangeable in this scene, we get the first images of the gooseflesh appearing on Nina’s skin. Something empowering seems to be happening. Whether it’s actual sexual liberation or the first signs of Nina embracing all these facets of herself (Beth, Erica, Lily), it complicates things. But what does it mean?

Well! I’ll go back to my original argument: Black Swan implies that these ideals for women can’t actually exist without women destroying themselves in the process of attaining them. How many identities can we effectively perform before we forget entirely who we are? Women struggle with that in a way that men never will. More often than not, it’s women who have to give up careers for children (Erica). They get pushed out of their professions when they get older (Beth). They’re expected to balance innocence with sexuality and to know when (and when not to) express them (Nina/Lily). And the attempt to balance, express, and suppress these prescribed roles often doesn’t work without having a detrimental impact on women individually and as a whole.

Interestingly, Nina and Lily both “die” in the end. So women in this film end up visibly crazy, hospitalized, or dead. In a less complex film, that would seriously piss me off. But the death and/or disappearance and/or insanity of these women make a larger point: if they’re all separate facets of Nina’s own personality and identity, which I believe they are, it’s necessary to watch each separate character struggle—it reinforces the idea that these performed identities aren’t possible without sacrificing one’s entire self.

You asked: If the Black Swan/White Swan “roles are (metaphoric) unattainable goals, how do we read those final moments?” Good question. It fascinates me most of all that Nina claims, after the White Swan’s suicide, that her performance was perfect. But, it wasn’t. She fell down in the middle of the damn ballet. To a gasping and appalled audience (not to mention, director). If her “I was perfect” claim applies only to the ballet, then she’s referring only to her performance as the Black Swan; after all, it’s the Black Swan whose dance partner whispers “wow” as she’s walking off stage; it’s the Black Swan whose audience gives her a standing ovation; it’s the Black Swan whose director beams with pride when she leaves the stage.

So yeah, I see Nina as a victim at the end of the film. Because she wasn’t perfect; she was never perfect. The conquering of her role as the Black Swan comes at a great sacrifice to her role as the White Swan (her fall during the ballet and her metaphoric death at the end of it). The two identities can’t coexist perfectly, as much as she wants them to. In the end, she still hasn’t attained the superhuman ability to perform competing identities for a critical audience. Sure, the audience may have loved Nina’s empowered, sexualized Black Swan, clearly enough to forgive the earlier screw up as the White Swan, but that isn’t surprising if you read the audience as a metaphor for society (why not?), a society that loves more than anything to be seduced by its women.

——————————-

We still have more to say! Let the conversation continue in the comments section, and leave links to reviews you’ve written or read.