This guest post by Kim Hoffman appears as part of our theme week on Female Friendship.

I was pretty excited about Sara’s 11th birthday party. Her mom owned a print shop and I was told we’d be having cake and playing games there; I enjoy the smell of paper so it didn’t seem like an odd place to have a party. After Sara opened presents we were outside at a picnic table lit by a floodlight from the print shop, glittering and bedazzling hats and T-shirts.

Sara’s birthday was in March, and just a few months before, a group of us went to the movies to see a new film called Now and Then. Since then, it was all any of us could talk about. We’d gone back to see it countless times, and one of those times, we were the only ones in the whole theater, a group of four or five of us girls, running around, doing cartwheels and singing and dancing. (I’d be remiss not to mention that I actually still have the original soundtrack, and it’s in my car as we speak.)

What Sara hadn’t told us was that her mom’s print shop was located right next door to a crematorium. It was a small grey building with a giant stone yard, filled with coffins of all sizes. I saw that my finished hat masterpiece was drying next to one that said the same thing as mine, “Teeny,” speckled with orange and yellow flower power decor. A blonde girl walked over with an impressed-looking grin on her face. “Wow, you actually look like Thora Birch,” she said to me. A few other girls formed around us and we all began to gush over our favorite movie of the year. A fancy car drove by at that very moment and we all squealed, pumping each other with a sugar high as if one of the actors from the movie was in our neighborhood, you know—cruising by the print shop and the crematorium on a dark Saturday night.

Now and Then wasn’t just a coming-of-age ‘90s girl movie. It was intersecting itself into my life as an 11-year-old fifth grader; I was same age as the characters in the film. And I felt we were all doing this “growing up” thing together. I cut out any clippings from magazines I could find on the movie, though it wasn’t hard because Devon Sawa, who played wormy Scott Wormer, was a common household name among girls my age. He was a teen heartthrob all over the pages of Tiger Beat and Bop and I instantly obtained both the movie soundtrack and the film score (and amassed a huge pile of pinup photos of Sawa). In 1995, there was a resurgence of the trippy hippie ‘60s style and I was obsessed with rock ‘n roll for the first time. The only thing my bedroom was missing was a lava lamp. You could say I didn’t care all that much about the boys in my class, just what my friends and I would do over the weekend at our upcoming sleepover. I savored this new art of forming real bonds with girlfriends.

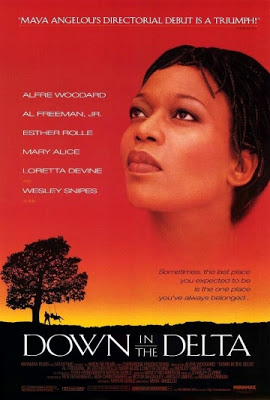

Now and Then is a film about four friends: Samantha, Teeny, Roberta, and Chrissy, who are growing up in the Midwest in the ‘70s (though much of the film was shot in Savannah, Georgia). A couple of decades have passed and Chrissy (played by Rita Wilson) is pregnant, living in her parents’ old home, and married to a guy she once thought was a mega dork. Teeny (Melanie Griffith) is a blossoming actress in Hollywood, with, as Roberta puts it, “Long legs, a tiny waist, and large, perky breasts.”

“Roberta you know how I feel about swearing,” Chrissy says back.

“Chrissy, breast is not a dirty word,” Roberta insists.

Which leads me to Roberta (Rosie O’Donnell), who has become a doctor and according to Chrissy, “Lives in sin with her boyfriend.” But more on that in a moment. Last but never least is Samantha (Demi Moore), a writer, and the narrator of this film; she is sarcastic, jaded, and arguably depressed. She explains that she hasn’t been to the Gaslight Addition in years (the neighborhood where all the girls grew up, which looks like any other midcentury American neighborhood). Now the girls reunite at their familiar stomping grounds for the arrival of Chrissy’s baby—and boy is she ready to pop. Waddling around in the house in a bow-tied muumuu dress, Chrissy opens up her home to her old friends, who awkwardly situate on the plastic-covered couch as if nothing’s changed in 25 years. Roberta is helping Chrissy around the house and offers the girls a beer, Samantha slinks into the backyard in all-black threads perfect for a moody writer, and Teeny inches through the yard in her heels, wearing a pearly white skin-tight skirt and matching jacket. As they play catch-up, they stare up at the treehouse they spent so much of their time as kids saving up money for, and slowly that eternal summer of their youth begins to skim back to the surface…

In our own little ways, my friends and I were making our own pacts for the first time—Sara, me, and our friend Taylor, plus the new girls we’d just met at Sara’s birthday. We would ride our bicycles from Taylor’s to Sara’s house, singing and laughing, stopping downtown at an old diner in the hopes we might see Janeane Garofalo in character as Wiladene, diner waitress by day, clairvoyant mystic by night. You could say I was enamored by this new, untapped part of me that the film was bringing out. I had a mix of confidence and fear—to explore, not just on our bicycles, but also in our minds—through séances and tarot cards, music and making up stories. (We commenced our friendship that night at Sara’s birthday party when we snuck over to that crematorium and had our first-ever séance.) We were in search of Dear Johnny in our own ways. But as our knees bobbed against one another’s and we formed a circle that night, I simply felt that brief but blissful form of excitement you feel when you’re a kid.

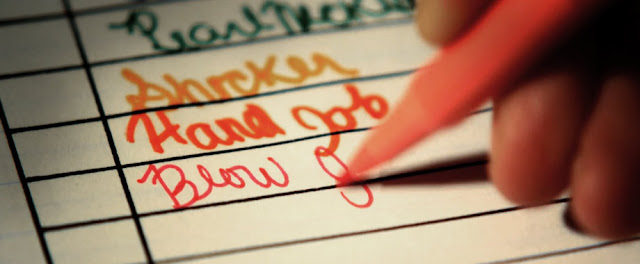

Now, the line about Roberta and her boyfriend “living in sin” is somewhat of a discussion among fans of the film, because word has it that from the beginning, Roberta’s character was written to be gay. I. Marlene King, writer, producer and director of Pretty Little Liars, was the writer on Now and Then. In earlier versions of the script, Chrissy says, “Roberta, for example, has chosen to be alternative, but she is still normal. She hasn’t been married four times or gone through a series of monogamous relationships…or wear all black. She’s happy. Aren’t you Roberta?” When the girls flash back to that summer when they were kids, we meet young Roberta (played by Christina Ricci), binding her chest and stumbling over her macho brothers wrestling in the hallway. Her mom died when she was four, and she is deeply bothered by it, refusing to succumb to any bullshit standards set aside for girls and the ways girls are supposed to dress or act.

Instead, Roberta is the girl at the softball game who’s throwing punches at boys or pranking her friends in a not-so-funny incident where she fakes drowning. She’s constantly testing her limits and the trust she so craves with the people in her life. But what she doesn’t yet understanding is that she needs to give others a chance to get through to her, too. Samantha (played by Gaby Hoffmann) is next to kin when it comes to tough-girl stuff because she’s in the midst of her parents’ divorce, and she’s completely in favor of rebelling against her clueless mother—which also means punching out a boy at a softball field if the moment calls for it, especially if she’s standing up for a friend. (I bet Sam is a Libra.) I used to wonder if there wasn’t more to Roberta and Sam’s relationship, especially because I could totally see Rosie O’Donnell and Demi Moore’s grown-up versions getting together and living “alternatively” as Chrissy puts it. Whatever happened in post-production to cause anyone to add in that line about Roberta’s boyfriend is a terrible shame.

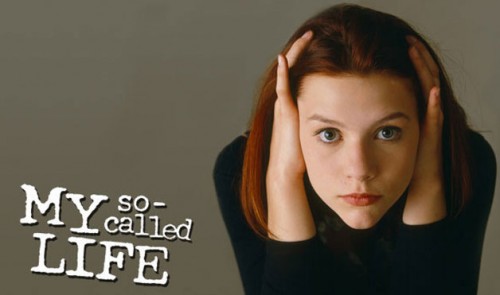

Young Teeny (played by Thora Birch) is the girl who sits on her roof and memorizes lines from old movies playing on the big drive-in screen. Her parents are always hosting lavish parties while she floats about in her room upstairs, obsessing over actresses from the Golden Hollywood heyday. Teeny is down for everything and anything, but we quickly get the sense that it’s all smoke and mirrors and in truth, she’s the least experienced, at least for right now. She stuffs her bra with vanilla pudding-filled balloons to bide her time before she reaches adolescence. (She got the idea from the Wormer boys after they surprise-attack the girls with water balloons.) Sex, dating, and romance—it’s all mysterious and lusty to her and she is rushing to grow up. In one of my favorite scenes in the movie, Teeny is making all the girls take a quiz and she discovers she’s a sexual magnet, “attracting men from all four corners of the world.” The look on her face as she reads her results say it all–she’s googly-eyed over all this possibility.

Sam is nothing like Teeny, but she doesn’t try to act prudish, she just prefers to focus on other things, like books, magic, science, and what really happened to Dear Johnny. She’s the one with the bag of candles and cards who’s happy to tote her wares to the cemetery. Sam has to look out for her little sister, but she also has to contend with her mom’s new dating life. Here, she’s expected to act mature and mind her manners, while she sees her mom dressing differently and gushing over a man who isn’t her father. Her only way to cope is to escape, and her friends support that; in their not-as-R-rated way, they’re basically saying, “Fuck that. We’re your family.” Sam and Teeny make great friends because they’re so out of each other’s way and they so easily understand this place their at in their lives—with Sam’s parents’ divorce and Teeny’s parents being nearly as absent under the same roof.

Roberta and Chrissy have a special bond that’s set to the side too, because they’re so opposite yet they balance each other’s personalities to a tee. Chrissy (played by Ashleigh Aston Moore) feels Roberta is her best friend. I can’t imagine what Chrissy’s mom must think of that—what if Roberta were to track mud into her pristine home? Chrissy’s bedroom is perfectly tidy and manicured pink. She is completely sheltered by her mother’s discussions about sex—and probably still believes a garden hose and a watering can are involved. She’s the last in line when the girls hit the road on their bicycles, and she’s the first one to say, “I’m not doing that,” when she feels uncomfortable or nervous. But a little mild giggling and convincing and the girls have Chrissy believing in herself and feeling connected to them in no time. Despite her doubts that she isn’t as pretty or skinny as the other girls, Chrissy manages to find her place in the group by just being Chrissy. That’s why Roberta makes such a great best friend. For her, friendship and acceptance isn’t about appearances. Chrissy has a heart of gold. A promise is a promise with her.

There is purpose to these friendships in Now and Then like there is purpose to Chrissy’s naivety about sex, Samantha’s imaginative curiosities, Teeny’s desires for passion in romance and career, and Roberta’s capacity for strength and weakness in equal measure. See, it was easy for all of us little girls who loved the film to attach ourselves to a character we related to or liked a lot because we too were on the verge of something—and being on the verge of anything is a beautiful and surreal feeling. When you’re 11, or 12, or 13, you are a part of this magical in-between moment that connects childhood with adolescence, and the friends you have during those few years may be some of the most important friends you will ever have—not because of how long they’ll be in your life, but because they’ll be the first people on board in your life journey who are up for the same adventures you are, and they’ll challenge you somehow—maybe to get in touch with your emotions when you’re embarrassed you cried in front of them, maybe to remind you that you’re all in this together. It’s the age where you’re searching for something, anything, and you’re old enough to find those things with your friends.

It wasn’t that long after Now and Then that I became the class scapegoat—they had decided I was weird. Instead of leaving it at that, they just had to hammer away at my self-esteem for good measure. What happened to riding our bikes, playing in our backyards, jumping into swimming pools and playing slumber party games? Now, friendship was considered by how much you impressed some queen bee, how far you’d go to stake your coolness. An eighth grade girl named Tara once saved me from a bathroom incident where a girl I once thought was my friend was mocking and making fun of me. I thought, “Here’s a true Roberta.”

I treasure the time around 1995 with an appreciation that goes soul deep. Those friends opened my eyes to the kinds of friends I would look for later on in my life, hoping to attract by weeding out the fair-weathered friendships, hardened, jealous-types, and egocentric bullies. Forget the thrill of being popular, well-liked, admired and noticed—those accolades are blips on the maps of our lives. Instead, relish in your weirdness, the glue that makes you who you are, and remember that embracing something weird is not a bad thing, it’s actually a wonderful thing; that’s the lesson I learned as a kid, when we snuck in to see Now and Then for the umpteenth time. Summer has always been a magical time where childhood lingers, and every time I get on a swingset again, or have a hankering for a push pop, or throw on my Now and Then soundtrack, I think of my childhood and feel invigorated with that rush of youth. I think of Taylor and Sara, and a time when we were so eager to make our own adventures. I also think of those four girls from the Gaslight Addition; somehow they affected my life by making me appreciate what it means to be and have a true friend in this wild world.

All for one and one for all.

Kim Hoffman is a writer for AfterEllen.com and Curve Magazine. She currently keeps things weird in Portland, Oregon. Follow her on Twitter: @the_hoff