This guest post written by Robert V Aldrich appears as part of our theme week on Interracial Relationships. Spoilers ahead.

Two of the greatest love stories in anime are interracial relationships.

Now, to be fair, that might seem a little surprising. After all, while generally being (or at least seeming) progressive on an array of social issues, the anime medium as a whole has a strained relationship with people of color, with the general absence of characters of color as, sadly, just the tip of the iceberg. When characters of color do appear, they are often highly generic (read: racist) stereotypes, although some popular anime cross the line and employ straight-up blackface antics (looking at you, Dragon Ball Z).

While the industry as a whole generally eschews characters of color, that hasn’t stopped some series from featuring prominent people of color characters in narratively significant stories. This has led to interracial couples being featured in two of the greatest anime series of all time: The Super Dimension Force Macross and Revolutionary Girl Utena.

Quick disclaimer: So, any discussion about race in anime needs to acknowledge the difficulties in identifying race in anime’s heavily stylized character designs. While some shows illustrate with more of an eye towards realism and racial distinctions can be made, most characters of white and Asian background are usually shown with nigh-identical features. This often makes distinguishing between the two races quite difficult (with nothing to say of distinctions between different ethnic groups within races). As such, it’s very easy for the token American woman to have largely the same facial features as her Japanese counterparts.

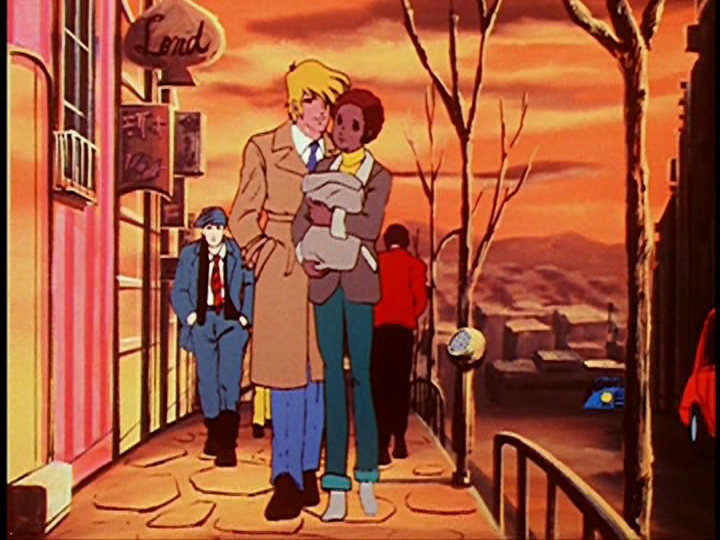

It’s for this reason that discussing interracial relationships can be a little tricky, simply because there are many more interracial relationships than first appears evident. For example, Aresene Lupin the Third (of Lupin III fame) is at the very least a quarter French (if not fully French), yet he is drawn with features comparable to fully Japanese characters (for example, his nemesis Inspector Zenigata). As such, his on-again/off-again dynamic with the patently Japanese Fujiko doesn’t seem interracial at all.

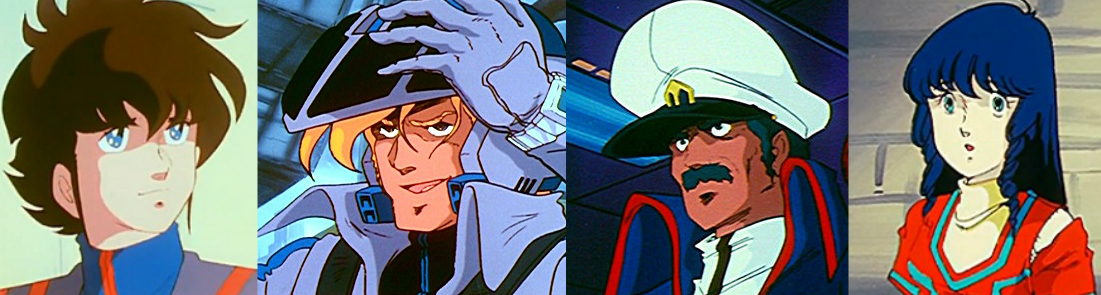

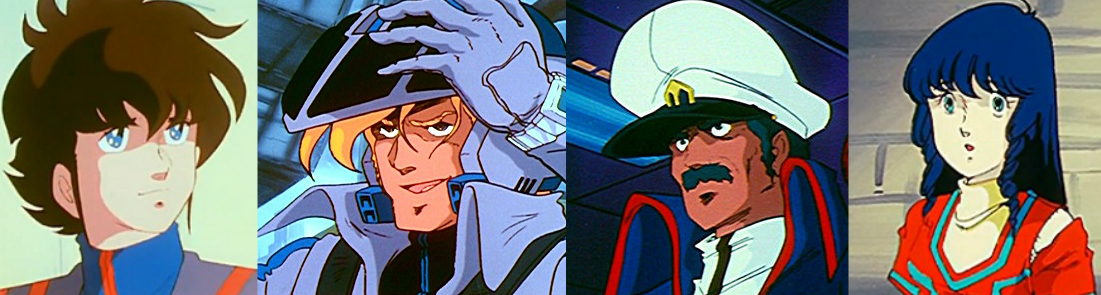

In Macross, the main protagonist Hikaru Ichijyo is drawn with features similar to his American friend Roy Focker, Russian captain Bruno Global, and even his Chinese pseudo-girlfriend Minmei.

This must be stated because it means that, technically, interracial relationships are actually quite common in anime; they are just very hard to distinguish. In order to draw attention to the very existence of interracial relationships, we will be discussing the very rare occurrences of a character of color not only being narratively significant (and not simply a one-off joke or a stand-alone episode), but involved with another equally narratively significant character of an obviously different race.

The Super Dimension Fortress Macross

Released in 1982, SDF Macross tells the story of Earth’s sole interplanetary vessel as it defends against an alien onslaught using reconfigurable aircraft. The story spans multiple years and features a wide array of characters, from grizzled war veterans to wide-eyed and naive starlets. It tells the story of survivors trying to endure the hardships that come as the cost of war, both on a community and culture and on the individual.

Most fans in the west know of SDF Macross as the basis for the first chapter in Robotech (an American product splicing together three separate Japanese shows, including Macross, to produce one three-generation narrative). Some elements of the show were amended for American/Western audiences but the vast majority of the story remained intact, including the violence and realism (well, as much realism as one can have in a show about a transforming aircraft). It would be this story that would introduce iconic anime characters like Hikaru Ichijyo (Rick Hunter in Robotech), Misa Hayase (Lisa Hayes), and many more. While Hikaru/Rick would be the main character and the story would follow his life and romances, a supporting story would be told following the tender love affair between command officer Claudia LaSalle (Claudia Grant) and ace fighter pilot Roy Focker (re-spelled Fokker in the U.S. for some reason).

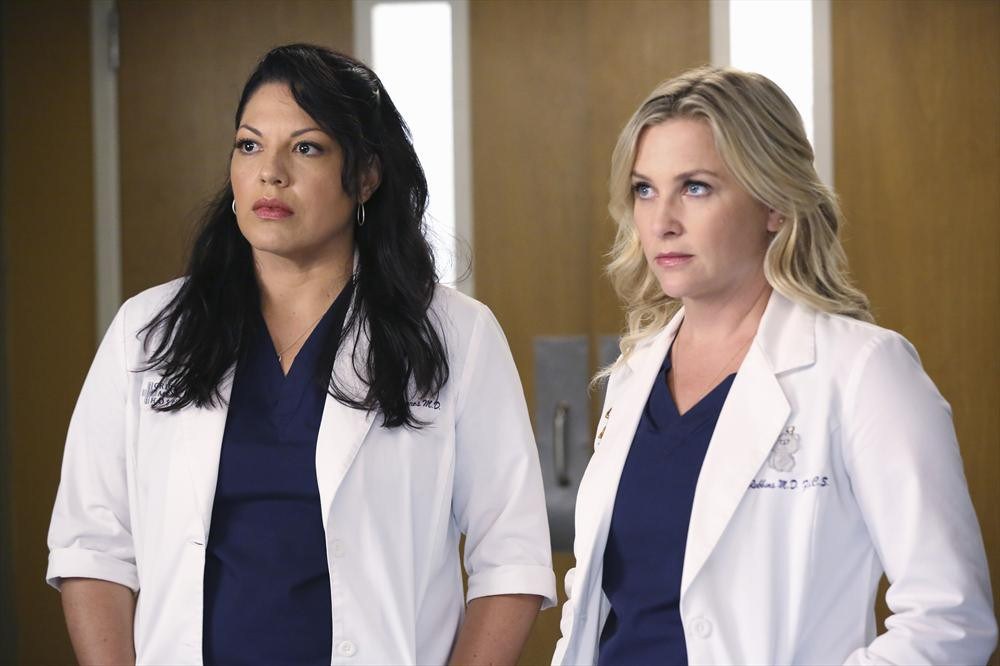

Claudia is the bridge officer in charge of weapons and navigation of the Macross (the giant space fortress that serves as the set and centerpiece of the show). She’s seen as a veteran officer and a mentor/big sister to other female characters in the show (especially Misa Hayase). She’s often the level-head in the bridge crew but also has a wild side as evidenced by her oft-referenced romantic life.

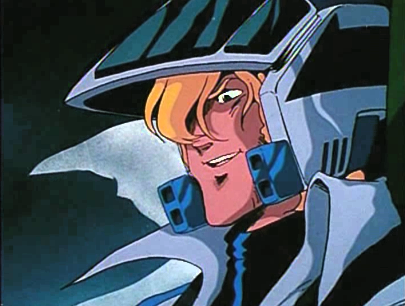

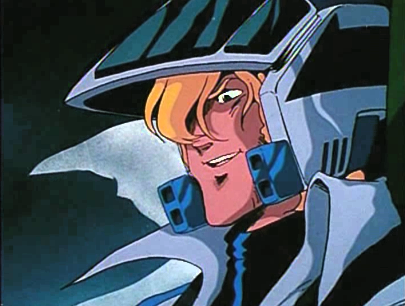

Opposite Claudia, we find Roy Focker. The ace fighter pilot for the humans against the early onslaught of alien forces, Roy seems to be the action hero of the first half of the story. At first glance, Roy is little more than an American stereotype. Tall, brash, and with copious blonde hair, he seems the antithesis to Hikaru’s Japanese stature and pacifist nature. This slowly evolves into a fully-formed character as we see Roy’s fraternal feelings for Hikaru as well as his romance with Claudia.

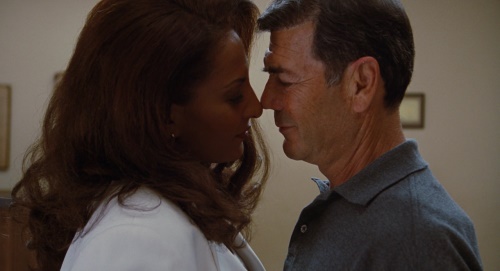

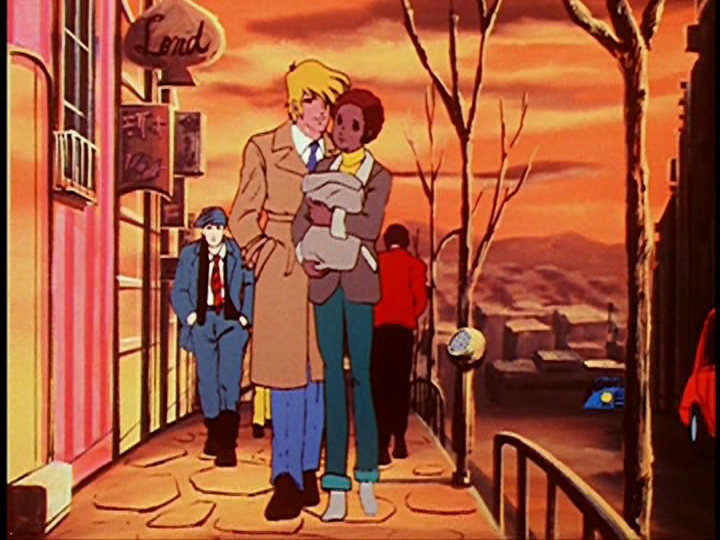

We see little evidences of Roy and Claudia’s romance throughout the first half of the show. They flirt after combat missions and we hear about their plans to see each other (events that usually transpire off-screen). In fact, our introduction to Claudia in the first episode includes Misa chastising her for her scandalous behavior with a night out with Roy the night before the big launch at the start of the show. Later, we see Claudia butting into Misa’s official exchange with Roy to tease him about his performance. All this builds to show an idealized relationship that includes passion and commitment.

And then Roy dies. (Uh…thirty-year-old spoiler alert?)

After a vicious dogfight with the alien ace pilot, Milia Fallyna (Miriya Parina Sterling in Robotech), Roy shakes off the suggestion that he go to the hospital. He instead retreats to Claudia’s apartment aboard the Macross. Despite coming out of a fight with her from an earlier episode, she makes pineapple salad for them during what should be rare quiet time together. Strumming away on a guitar, Roy slips from life on Claudia’s couch.

The pallor of Roy’s death hangs over the characters for the remainder of the show, affecting everyone in ways big and small. Claudia grows a bit melancholy in the wake of Roy’s absence but continues to soldier on. She clearly carries warm memories of Roy, as best evidenced when she advises Misa about her romance with Hikaru. During a late-season flashback, we are treated to a full episode of Roy and Claudia’s relationship when it first blossomed. We see Claudia as a stiff junior officer and Roy as a careless and callous fighter jock. They are at odds with one another until Claudia discovers Roy at her door during a rainstorm, determined to explain to her his feelings and to make her understand why he is who he is. Their love blossoms from there and becomes the stuff of legend.

Roy and Claudia’s relationship is not perfect. It is not ideal. It is tested constantly by the working lives of two professionals in tense situations with impossibly high stakes. Yet despite their backgrounds and despite their differences, their love for one another is undeniable.

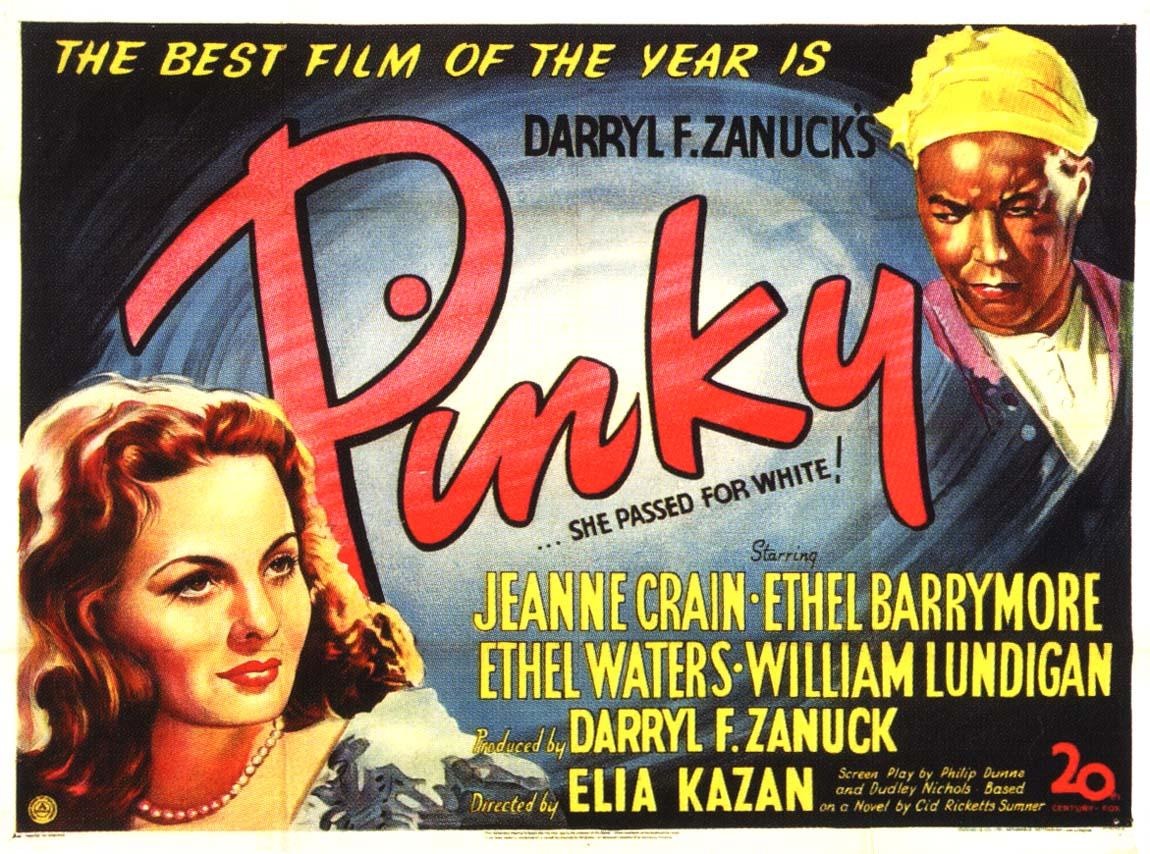

To fans in the 1980s, tuning in on Saturday mornings, this was quietly subversive. In the west, television shows were (and still are) lacking people of color, except occasionally in a single token role. To see a Black woman in a leading role (whose name wasn’t Uhura) was something many fans still remember distinctly. But an interracial love affair? There were states in the US where that was technically still illegal! And here it was, not only on a beloved cartoon, but depicted beautifully, with the respect to be realistic but also the idealism to be wonderful.

Revolutionary Girl Utena

Whereas Macross would see Claudia and Roy’s love in the background of the larger story of humanity persevering against annihilation (as well as the far less satisfying love triangle between Hikaru and Misa and Minmei), 1997’s Revolutionary Girl Utena would put the interracial relationship front and center. It did this by not just involving the two main characters of the story, but by making their love the very centerpiece of the whole story.

The story of Revolutionary Girl Utena revolves around a sword-fighting contest at an elite private school where the prize for victory is the hand of the lovely and demure Anthy Himemiya. Anthy is of indeterminate racial background, but most guesses is that she is Indian or of Indian descent. While she is drawn with dark skin tones in the comic and early episodes of the animated series, Anthy’s skin tone is noticeably lightened in later depictions, most notably the 1999 feature film.

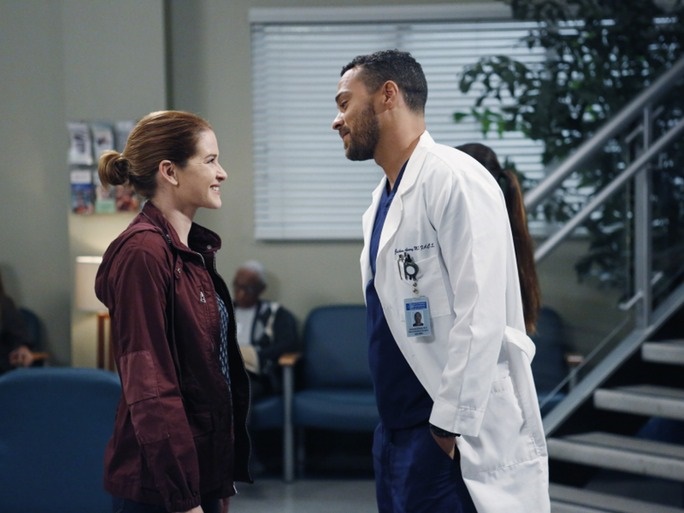

As the centerpiece of the series, Anthy is an initially enigmatic figure who appears to be little more than an abused damsel in distress, being passed around between the elites of the school. The heroine of the show, Utena Tenjou, more or less stumbles into rescuing her from the monstrous Saionji, resulting in the two being bonded to one another. Their relationship is extremely awkward at first, as much due to their same gender as well as simply being set in the adolescence of life, but their feelings slowly blossom as the series progresses, approaching thinly-veiled romantic overtones throughout the later episodes (and even explicitly stating a sexual dynamic in the film).

The issue of a sapphic connection between the two is very much a running theme in the story. Whispers of lesbianism are shared throughout the show, which makes the tomboy Utena uncomfortable and often explode defensively (at least initially). As the show progresses, the issue of same-sex love takes a backseat as the stakes raise for Anthy’s hand (and the inferred cataclysmic implications of her affection). Whatever novelty there is in their connection is lost as Utena fights for Anthy’s freedom and even her very life. When the final turn comes, the heartbreaking rejection that occurs leaves both characters transformed and arguably not for the better.

Fans of all persuasions gravitated towards the bold love story on display. As the world wrestled (and continues to wrestle) to address issues of gender and sexuality, where the words “gay” and “lesbian” were often still whispered, Revolutionary Girl Utena came out brashly, confronting these issues head-on. To do so while also tackling an interracial couple underscored the pervasiveness of many prejudices and preconceived notions. On full display was a love story that trumped many of the legends of old and simultaneously blew away every single reservation and preconceived notion along with it.

In both of these classic anime series, the racial background of the respective love interests is never made an issue. Nobody remarks to Claudia that her race is an issue in her seeing Roy. Nobody makes an issue of Anthy’s race or ethnicity as she dates Utena. Anthy and Utena don’t even see any real protest regarding their same-sex relationship (regardless of however real or imagined it is at the time). With regards to Roy and Claudia’s pairing, the only protests are internal to Claudia as the relationship begins.

While Claudia would largely disappear from the spotlight of Macross/Robotech fandom as the franchise moved on, Anthy remains a popular character, especially among non-white cosplayers. As a rare character of color in a major series, and as the cornerstone of that series, she’s seen as an icon and deservedly so. She has few peers among a vast sea of comparative homogeny when it comes to character types. While styles, personalities, and all manner of characteristics vary widely in anime, ethnicity and race seem rarely varied. Characters like Anthy and Claudia are welcome respites from that monotony.

That their relationships are unrestrained is even more noteworthy. Claudia’s relationship with Roy is never questioned, and certainly not on the bounds of their differing ethnicity. Anthy and Utena are likewise free from such criticisms (though, to be fair, they have far bigger oppositions in the story).

Anime is not free of racism. Anime, as a whole, has an uncomfortable dearth of characters of color. While that trend is changing, we still see a long way to go. It is comforting, if only a little, that what few characters are depicted and shown so prominently, are free of many of the restrictions of love we see in much of the world today. Claudia and Roy’s relationship is simultaneously realistic and perfect, striking the balance of believability and idealism that we look for in fiction. Anthy and Utena’s love starts accidentally and burns slowly, until it ignites like a flame. Their love story is the stuff of legend and will live on in the annals of great love stories in fiction, anime or otherwise.

With interracial couples sorely lacking in popular depictions in all media, it is comforting to find not only examples in anime (however admittedly rare) but to find sterling examples that inspire hope for any love, no matter the persuasion. Plus, these two love stories are set against dramatic swordfights and pronounced dogfights with transforming aircraft.

Robert V Aldrich is a novelist based out of North Carolina where he lives in denial about his bald spot. He can be found on Twitter at @Rvaldrich, Facebook, at his website Teach The Sky, and at parties talking to the dog. When he’s not writing, he works as a convention speaker, cancer researcher, and martial arts instructor.