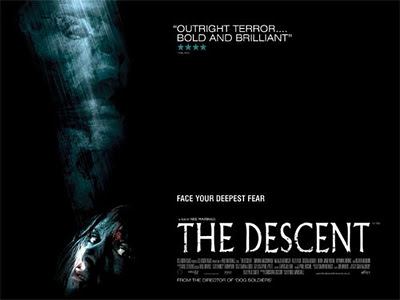

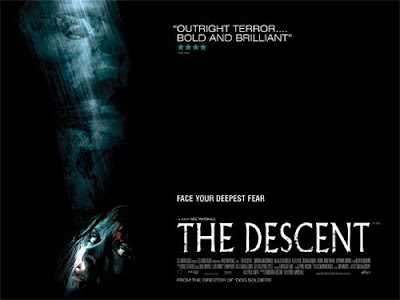

When I first heard of The Descent, around the time of its 2006 theatrical release, it was described to me as “a movie about a bunch of lesbians who go into a cave and there are monsters.”

Horror Week 2011: The Blair Witch Project

|

| The Blair Witch Project (1999) |

Viewers might hope that with its unconventional approach, shoestring budget, and status as the first blockbuster powered by Internet buzz, The Blair Witch Project could offer horror fans something they haven’t seen before, specifically in terms of how women are represented. At first, the flick looks promising because it centers on a female lead in a position of authority. While it’s arguable whether The Blair Witch Project’s through-the-viewfinder conceit is actually innovative (cinephiles like to point to the correlations between Blair Witch and Man Bites Dog and Cannibal Holocaust), it’s safe to say that—in 1999, at least—no films with this particular conceit had enjoyed such widespread popularity. The presence of this conceit might account for the film’s success, coming as it did in the watershed era of reality television. Its lo-fi, DYI qualities lend the film a realism that at that time felt new and potentially persuasive. While the ensuing years have brought us further variations on the motif—Cloverfield, Paranormal Activity, and Super 8, among others—it’s also become much easier to see how The Blair Witch Project, for all its putative realism, renders unduly harsh judgments on its female lead.

Horror Week 2011: Drag Me to Hell

This review, written by Stephanie Rogers, was originally published in June 2009.

But, I ask you, can a film that sacrifices a goat and a kitten really be taking itself so seriously?

Everything that exists in this movie is a stereotype: the skinny blonde who used to be fat and now refuses to eat carbs, the skinny blonde’s self-hatred and rejection of her farm-girl roots, the rich boyfriend who will undoubtedly help her escape it all, his rich and consequently vapid, overbearing parents who want their son to marry a nice upper-class girl, the patriarchal workplace where the skinny blonde gets sent for sandwiches by her male coworkers, the jerk who sells out a coworker in order to get promoted, the brown-skinned psychics who hold hands around a table and chant in an attempt to invoke The Evil Spirit, the gypsy, obviously, and not least importantly, the fucking goat sacrifice.

Everything that exists in this movie is a stereotype: the skinny blonde who used to be fat and now refuses to eat carbs, the skinny blonde’s self-hatred and rejection of her farm-girl roots, the rich boyfriend who will undoubtedly help her escape it all, his rich and consequently vapid, overbearing parents who want their son to marry a nice upper-class girl, the patriarchal workplace where the skinny blonde gets sent for sandwiches by her male coworkers, the jerk who sells out a coworker in order to get promoted, the brown-skinned psychics who hold hands around a table and chant in an attempt to invoke The Evil Spirit, the gypsy, obviously, and not least importantly, the fucking goat sacrifice.

The point is: it’s hard to play the I-hated-this-movie-because-of-the-blah-blah-“insert offensive stereotype”-game, when the film unapologetically turns everyone into a caricature.

Drag Me To Hell is about a young woman, Christine (played by Alison Lohman), who makes a questionable decision in an effort to get promoted at the bank where she works. She refuses to give a third extension on a woman’s mortgage loan, and in doing so, the woman, Mrs. Sylvia Ganush (played by Lorna Raver), could potentially lose her home. The twist? Christine could’ve given her the extension. But she chose not to. Instead, Christine wanted to prove to her boss that she’s a tough, hard-nosed, business savvy go-getter, and therefore certainly more qualified than her ass-kissing male coworker (who she’s in the process of, ahem, training) to take over the assistant manager position.

Then, as luck would have it, all hell breaks loose.

For the next hour and a half, these women go all testosterone and maniacally kick each other’s asses. This isn’t an Obsessed-type ass-kicking, where Beyonce Knowles beats the crap out of Ali Larter over, gasp, a man! and where all that girl-on-girl action plays like late-night Cinemax porn for all the men in the house. (Read Sady Doyle’s excellent review of it here). No, this is strictly about two women, one old, gross, and dead, the other young, gorgeous, and alive, trying to settle a score. Christine wants to live, dammit! And Mrs. Ganush wants to teach Christine a lesson for betraying her in favor of corporate success!

For the next hour and a half, these women go all testosterone and maniacally kick each other’s asses. This isn’t an Obsessed-type ass-kicking, where Beyonce Knowles beats the crap out of Ali Larter over, gasp, a man! and where all that girl-on-girl action plays like late-night Cinemax porn for all the men in the house. (Read Sady Doyle’s excellent review of it here). No, this is strictly about two women, one old, gross, and dead, the other young, gorgeous, and alive, trying to settle a score. Christine wants to live, dammit! And Mrs. Ganush wants to teach Christine a lesson for betraying her in favor of corporate success!

I vacillated between these two women throughout the movie, hating one and loving the other. After all, Christine merely made a decision to advance her career, a decision that a man in her position wouldn’t have had to face (because he wouldn’t have been expected to prove his lack of “weakness”). If her male coworker had given the mortgage extension, I doubt it would’ve necessarily been seen as a weak move. And even though Christine made a convincing argument to her boss for why the bank could help the woman (demonstrating her business awareness in the process), her boss still desired to see Christine lay the smack-down on Grandma Ganush. I sympathized with her predicament on one hand, and on the other, I found her extremely unlikable and ultimately “weak” for denying the loan. (Check out the review at Feministing for another take on this.)

Mrs. Ganush, though, isn’t your usual villain. She’s a poor grandmother, who fears losing her home. She literally gets down on her knees and begs Christine for the extension. Sure, she hacks snot into a hankie and gratuitously removes her teeth here and there, but hey, she’s a grandma, what’s not to love? Other than, you know, evil.

I love that this movie is about two women who are both arguably unlikeable to the point where you hope they either both win or both die. (The last time I remember feeling that way while watching a movie was probably during some male-driven cop/gangster drama. Donnie Brasco? American Gangster? Goodfellas? Do women even exist in those movies?) Everyone else is a sidekick, including the doe-eyed boyfriend (played by Justin Long), who basically plays the stand-by-your-(wo)man character usually reserved for women in every other movie ever made in the history of movies, give or take, like, three.

I love that this movie is about two women who are both arguably unlikeable to the point where you hope they either both win or both die. (The last time I remember feeling that way while watching a movie was probably during some male-driven cop/gangster drama. Donnie Brasco? American Gangster? Goodfellas? Do women even exist in those movies?) Everyone else is a sidekick, including the doe-eyed boyfriend (played by Justin Long), who basically plays the stand-by-your-(wo)man character usually reserved for women in every other movie ever made in the history of movies, give or take, like, three.

But at the same time, one could certainly argue that Christine’s unwillingness to help Mrs. Ganush, which results in Christine spending the next three days of her life desperately trying not to be dragged to hell, plays as a lesson to women: you can’t get ahead, regardless, so just stop trying. (Dana Stevens provides an analysis on Slate regarding this double-edged-sword dilemma that Christina finds herself in.)

Some have also argued that Drag Me To Hell exists in the same vein as the Saw films: it’s nothing but torture porn and obviously antifeminist. Yes, it’s gory, with lots of nasty stuff going in and out of mouths (Freud?), but the villain gets her share, and Christine hardly compares to the traditional heroine of lesser gore-fests: for one, she’s strong, much stronger than the horror-girls who can’t seem to walk without falling down in their miniskirts, and for the most part, she makes life-or-death decisions on her own, growing stronger and more adept as she faces the consequences of those decisions.

Some have also argued that Drag Me To Hell exists in the same vein as the Saw films: it’s nothing but torture porn and obviously antifeminist. Yes, it’s gory, with lots of nasty stuff going in and out of mouths (Freud?), but the villain gets her share, and Christine hardly compares to the traditional heroine of lesser gore-fests: for one, she’s strong, much stronger than the horror-girls who can’t seem to walk without falling down in their miniskirts, and for the most part, she makes life-or-death decisions on her own, growing stronger and more adept as she faces the consequences of those decisions.

Perhaps most importantly, Christine isn’t captured by some sociopathic male serial killer and helplessly tortured in a middle-of-nowhere shed for five days. She trades blows with her attacker, and at one point, in pursuit of Mrs. Ganush, she even states that she’s about to go, “Get some.” (Ha.)

I personally read the film as an attempt to uphold the qualities our society traditionally categorizes as “feminine” characteristics: compassion, understanding, consideration, etc. I’m not suggesting that men don’t also exhibit these qualities, but when they do, they’re often considered weak and unmanly, especially when portrayed on-screen, which is demonstrated quite effectively when Christine confronts her male coworker about his attempts to sabotage her career; he bursts into tears in a deliberately pathetic played-for-laughs diner scene.

But it’s only when Christine rejects these qualities in herself (the sympathetic emotions she initially feels toward Mrs. Ganush), and consciously coaxes herself into adopting hard-nosed, traditionally “masculine” characteristics (which her male boss rewards her for), that she’s ultimately punished—and by another woman, no less. The question remains, though, is she punished for being a domineering corporate bitch, or is she punished for rejecting her initial response to help out? Regardless of the answer, the film makes a direct commentary on the can’t-win plight of women in the workplace, and, newsflash: it still ain’t pretty.

Watch the trailer here.

Horror Week 2011: Hellraiser

|

| Hellraiser (1987) |

When people talk about classic horror movies, they’re almost always referring to the eighties which contained Nightmare on Elm Street, The Thing, and Child’s Play to name a few. Hellraiser, released in 1987, is no exception. While the movie lacks a lot of the high-tech special effects we’ve grown used to in contemporary cinema, the make-up in Hellraiser is impressively chilling. Although I’d seen the film several times prior (including all its sequels), I still found myself cringing and gagging as Frank emerged from the floorboards as little more than a slimy substance with bones.

“What’s the matter? It’s what you brought me here for, isn’t it?”

“I suppose so, yes.”

“So what’s your problem? Let’s get on with it.” And as Julia’s reluctance seems to grow, he growls, “You aren’t going to change your fucking mind, are ya?”

Tatiana Christian is a blogger at Parisian Feline, who writes about sexuality, gender and basically her thoughts on social justice and life. She previously contributed a review of Slumdog Millionaire to Bitch Flicks.

Horror Week 2011: The Sexiness of Slaughter: The Sexualization of Women in Slasher Films

Over the course of the series’ eight one-hour episodes, those skilled and sexy enough to command the screen survive. Those who don’t will “get the axe” until only one strong, seductive and stellar actress remains, earning the break-out role in “Saw VI” and the title of Scream Queen.

The season 1 winner, Tanedra Howard, won the chance to show audiences just how seductive and stellar she could look while being tortured.

As years passed, young audiences required that gruesome images become more intense and explicit for them to become scared…In 1978, a movie called Halloween not only sold more tickets than any other horror film, it broke all previous box-office records for any type of film made by an independent production company. Hollywood immediately tried to tap into the success of Halloween. Films such as Friday the 13th, Don’t Go In the House, Prom Night, Terror Train, He Knows You’re Alone, and Don’t Answer the Phone were all released in 1980. These movies, which are some of the first slasher films, were extremely successful. However, with their increasing popularity came strong criticism. Slasher films were condemned for frequently portraying vicious attacks against mostly females and for mixing sex scenes with violent acts.

This popular kill from Jason X involves scientist Andrea getting her face dunked in liquid nitrogen. While struggling with Jason, Andrea’s shit (half of what could be a sexy scientist Halloween costume) rides up revealing to the audience the bottom of her full breasts. While this small glimpse does not equate itself to the arousal of an all-out sex scene, it is intentional. From costuming to blocking, every aspect of the character’s femininity in this scene was meticulously plotted. The fact that filmmakers, audiences, and Maxim find a kill scene more enticing if the woman is sexy and almost shirtless speaks to the fact that modern horror films sexualize slaughter.

Social scientists have expressed concern over the negative effects that slasher films may have on audiences. In particular, exposure to scenes that mix sex and violence is believed to dull males’ emotional reactions to filmed violence, and males are less disturbed by images of extreme violence aimed at women (Linz, Donnerstein & Adams, 1989). These effects on male viewers are said to derive from “classical conditioning”.

Sapolsky and Molitor rebuff this idea, believing that the pairing of sex and violence does not occur often enough for classical condition to occur. However, they further state:

The concern over potential negative effects of exposure to slasher films remains. Possibly, depictions of violence directed at women as well as the substantial amount of screen time in which women are shown in terror may reduce male viewers’ anxiety. Lowered anxiety reduces males’ responses to subsequently-viewed violence, including violence directed at women. Accordingly, the desensitizing effects of slasher films may result from a form of “extinction” and not from classical conditioning.”

It appears that no matter how you slice it, this pairing, on unconscious level, does not leave viewers unaffected.

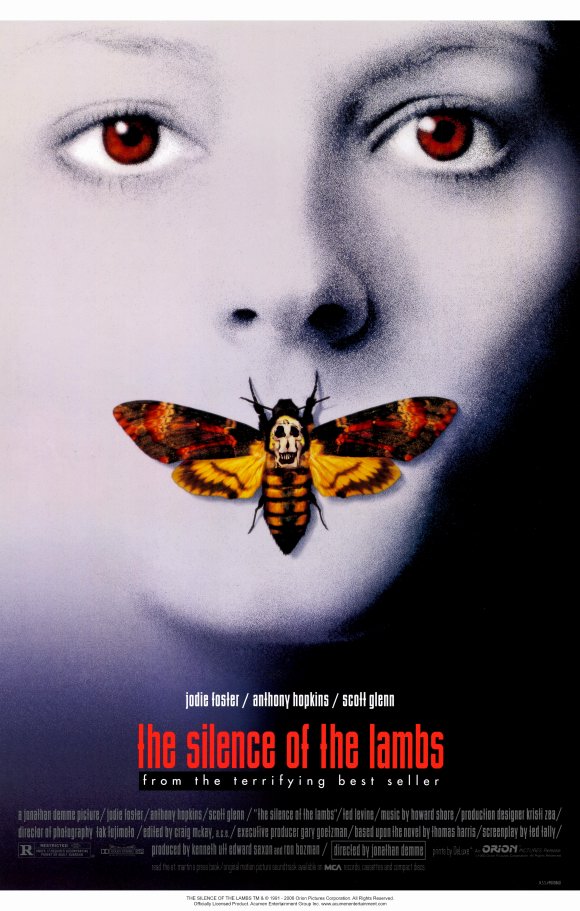

Horror Week 2011: The Silence of the Lambs

|

| The Silence of the Lambs (1991) |

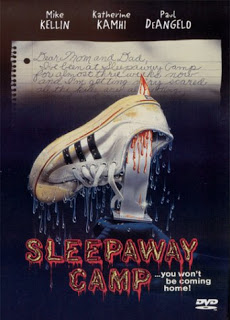

Horror Week 2011: Sleepaway Camp

|

| Sleepaway Camp (1983) |

But Angela’s not deceiving everybody because she’s a trans* person. She’s deceiving everybody because she’s a (fictional) trans* person created by cissexual filmmakers. As Drakyn points out, the trans* person who’s “fooling” us on purpose is a myth we cissexuals invented. Why? Because we are so focused on our own narrow experience of gender that we can’t imagine anything outside it. We take it for granted that everyone’s gender matches the sex they were born with. With this assumption in place, the only logical reason to change one’s gender is to lie to somebody.

Horror Week 2011

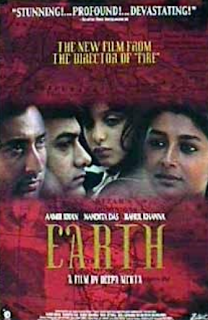

Director Spotlight: Deepa Mehta

|

| Deepa Mehta |

| Heaven on Earth (2008) |

When Chand (played by Bollywood superstar Preity Zinta) arrives in Brampton, Ontario to meet her new husband, she leaves behind a loving family and supportive community. Now, in a new country, she finds herself living in a modest suburban home with seven other people and two part-time tenants. Inside the home, she is at the mercy of her husband’s temper, and her mother-in-law’s controlling behaviour.

After a magic root fails to transform her husband into a kind and loving man, Chand takes refuge in a familiar Indian folk tale featuring a King Cobra.

Watch the trailer:

|

| Water (2005) |

In 1938, Gandhi’s party is making inroads in women’s rights. Chuyia, a child already married but living with her parents, becomes a widow. By tradition, she is unceremoniously left at a bare and impoverished widows’ ashram, beside the Ganges during monsoon season. The ashram’s leader pimps out Kalyani, a young and beautiful widow, for household funds. Narayan, a follower of Gandhi, falls in love with her. Can she break with tradition and religious teaching to marry him? The ashram’s moral center is Shakuntala, deeply religious but conflicted about her fate. Can she protect Kalyani or Chuyia? Amid all this water, is rebirth possible or does tradition drown all?

Watch the trailer:

|

| Bollywood/Hollywood (2002) |

After Rahul’s white pop-star fiancée dies in a bizarre levitation accident his mother insists he find another girl as soon as possible, preferably a Hindi one. As she backs this up by postponing his sister’s wedding until he does so, he feels forced to act, the more so as he knows his sister is pregnant. But it’s a pretty tall order for an Indian living in Ontario, so when he meets striking escort Sunita who can ‘be whatever you want me to be’ he hatches a scheme to pass her off as his new betrothed. Things get complicated when his family start to take to her and he realises his own feelings are becoming rather stronger than that.

Watch the trailer:

|

| Earth (1998) |

Earth is the second film in Mehta’s Elements Trilogy. The film seems to have won only a single award, and is based on Bapsi Sidhwa’s novel, Cracking India. Released in India as 1947: Earth, the film chronicles the division of India and Pakistan. From a plot summary on IMDb:

This story revolves around a few families of diverse religious backgrounds, namely, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and Parsi, located in Lahore, British India. While the Parsi family, a known minority in present day India, are prosperous, the rest of the families are shown as struggling to make a livelihood. Things change for the worse during 1947, the time the British decide to grant independence to India, and that’s when law and order break down, and chaos, anarchy, and destruction take over, resulting in millions of deaths, and millions more rendered homeless and destitute. In this particular instance, Shanta is a Hindu maid with the Sethna (Parsi) family, who is in love with Hassan, a Muslim, while Dil Navaz loves Shanta, and wants her to be his wife, she prefers Hassan over him. This decision will have disastrous effects on everyone concerned, including the ones involved in smuggling Hindus across the border into India.

Watch the trailer:

|

| Fire (1996) |

Fire is the first film to confront lesbianism in a culture adamantly denying such a love could ever exist. Shabana Azmi shines as Radha Kapur in this taboo-breaking portrayal of contemporary India and the hidden desires that threaten to defy traditional expectations. In a barren, arranged marriage to an amateur swami who seeks enlightenment through celibacy. Radha’s life takes an irresistible turn when her beautiful young sister-in-law seeks to free herself from the confines of her own loveless marriage and into the supple embrace of Radha.

Watch the trailer:

Mehta’s films not mentioned here include Sam & Me, Camilla, The Republic of Love, and more.

In ‘Women, War & Peace’s ‘I Came to Testify’ Brave Bosnian Women Speak Out About Surviving Rape as a Weapon of War

“Their testimonies would embody the experience of hundreds of women held captive in Foca.”

In Foca, half the residents, 20,000 Muslims were just gone. All 14 mosques were destroyed. Evidence in Foca showed that a campaign could be built to prove that a systematic, organized campaign of rape had been “used as an instrument of terror.” While the UN estimated 20,000 women raped in Bosnia, others say it was more like 50,000.

In Foca, half the residents, 20,000 Muslims were just gone. All 14 mosques were destroyed. Evidence in Foca showed that a campaign could be built to prove that a systematic, organized campaign of rape had been “used as an instrument of terror.” While the UN estimated 20,000 women raped in Bosnia, others say it was more like 50,000.

“Rape was used not only for the immediate impact on women but for the long-term destruction on the soul of the community.”

“Rape is the worst form of humiliation for any woman. But that was the goal: to kill a woman’s dignity.”

“…The people who came and testified were able to maintain their dignity and they didn’t let the perpetrators take their humanity away from them. So yes in one sense they were victims. But in another sense, they were the strong ones. They survived.”

“Looking at pictures of Nuremberg, it’s mostly men…women aren’t given a place at the table, even as a witness…”

“War criminals wouldn’t be known & there would be no justice if witnesses didn’t testify…I was glad to be able to say what happened to me and to say who had done this to me & my people. I felt like I had fulfilled my duty. I came to look him in the face. I came to testify.”

Megan contributed reviews of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played with Fire, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, Something Borrowed, !Women Art Revolution, The Kids Are All Right (for our 2011 Best Picture Nominee Review Series), The Reader (for our 2009 Best Picture Nominee Review Series), Game of Thrones and The Killing (for our Emmy Week 2011), as well as a piece for Mad Men Week called, “Is Mad Men the Most Feminist Show on TV?” She was the first writer featured as a Monthly Guest Contributor.

Quote of the Day: Andi Zeisler

|

| Andi Zeisler, Co-Founder of Bitch Magazine |

Here’s Zeisler on the word “bitch:”

People want to know whether it is still a bad word. They want to know whether I support its use in public discourse. Or they already think it’s a bad word and want to discuss whether its use has implications for free speech or sexual harassment or political campaigns.[…]

So here goes: Bitch is a word we use culturally to describe any woman who is strong, angry, uncompromising and, often, uninterested in pleasing men. We use the term for a woman on the street who doesn’t respond to men’s catcalls or smile when they say, “Cheer up, baby, it can’t be that bad.” We use it for the woman who has a better job than a man and doesn’t apologize for it. We use it for the woman who doesn’t back down from a confrontation.

So let’s not be disingenuous. Is it a bad word? Of course it is. As a culture, we’ve done everything possible to make sure of that, starting with a constantly perpetuated mindset that deems powerful women to be scary, angry and, of course, unfeminine — and sees uncompromising speech by women as anathema to a tidy, well-run world.

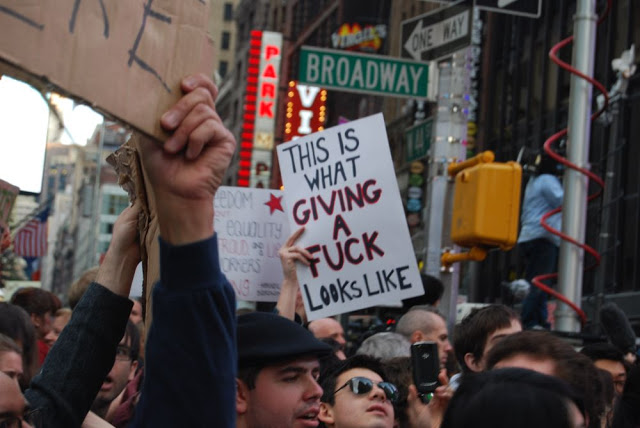

Occupy Wall Street and Feminism and Misogyny (Oh My?)

The New York Times, the highly respected New York Times, did a great article yesterday about Occupy Wall Street. The entire report revolved around how Occupy Wall Street is a big pain in the ass to the area’s public bathrooms. Now there’s two things you need to know about the last sentence I just said. A: I’m not kidding. B: The double entendre was unintended. There will be several more of those in the following three minutes, and all of them are unintended except for seven. The New York Times, which is a so-called liberal media outlet, is more concerned about the harm done to the public restrooms than they are with the harm done to the American people by corporations and Wall Street titans who make Charlie Sheen’s moral compass look like that of Harriet Tubman. As billionaires continue to shit all over this country like it’s a bathroom near Occupy Wall Street, the media is more worried about the bathrooms near Occupy Wall Street? Are you fucking serious? Get your head out of your ass, and maybe you’ll be able to better see your priorities. This world is a shit storm of greed that desperately needs mopping up. We’re talking about people’s homes, people’s lives, people’s dreams, and the media wants to make it about the discomfort of millionaires who live around Liberty Square? The article said mothers have trouble getting strollers around police barricades. God forbid the revolution should get in the way of your evening stroll with pookie wookie. This may not be a revolution in the traditional sense, but this is a revolution of thought. Americans are tired of greed over good, profitable pollution over people, war for wealth over the welfare of average workers. This is a thought revolution, and the revolution will not be sanitized. It will be criticized, ridiculed, intentionally misconstrued, and misunderstood. But it’ll push through. Shit all over it all you want, but the floodgates are open now. The revolution will not be tidy. The revolution will not fit with your Pilates schedule. The revolution will not be quiet after 10 pm, and it will not fit easily into a mainstream media- defined paradigm. The revolution will affect your bottom line. The revolution will affect you whether you ignore it or not. The revolution will not be dissuaded by barricades or pepper spray, driving rain, police raids, or ankle sprains. It’s like the postal service on steroids; pepper spraying us is like throwing water on gremlins—the more you do it, the more of us show up. The revolution will be annoying to the top 1% and those who aren’t open minded enough to understand it. The revolution does not care if you satirize it; you still won’t be able to jeopardize it. The revolution will not wait until after your hair appointment, your dinner party, tummy tuck, or titty tilt. The revolution does not care about your lack of intellectual curiosity. The revolution will not be televised, but it will be digitized and available on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and anywhere real ideas are told. The revolution will not be hijacked by your old, tired, rejected political beliefs. The revolution will make politicians squirm, bankers bitch, elites moan, and those with Stockholm Syndrome scream, “Hit me, punk criminal assholes. Shut up and do what our captors told you. There’s a sitcom on about a chubby guy who hates his wife, and we’re supposed to watch it. Now fall in line.” The revolution will not be monetized, commercialized, circumcised, or anesthetized. Good god, don’t you get it? Greed is no longer good, and it’s not god. The thought revolution is here to stay whether you give two shits about it or not. The revolution would, however, like to apologize for shitting all over your apathy. Now pick a side.

If we are not willing to invest in the very programs that will help pull some of our poorest Americans—single mother led households and women of color—out of the spiral, then we are not rebuilding the economy. We are only as strong as our most vulnerable, as the saying goes. To continue a national discussion on unemployment and the recession without acknowledging that our women and children are suffering the most, not because we aren’t able to implement programs and pass legislation like universal, affordable child care, paid sick days, increased food stamp benefits, fair pay standards and more but because we aren’t willing to do so, is something we must own up to and do something about if we are to rise above these hard times and come out stronger than we were when we headed into the recession.

When we think about the elite 1 percent in a position of economic and political power in America, we have to recognize that those elites are predominantly straight, white men. Their position of power is upheld by patriarchy, by white privilege, by heteronormativity. If we want to dismantle oppression in our society, we can only hope to do so by recognizing the ways in which these various systems of oppression intersect and support one another. That doesn’t mean we can’t focus on the economy as a nexus of inequality; clearly, the occupation of Wall Street speaks directly to fighting corporate power and economic privilege. But we cannot imagine creating a society rooted in equality without fighting for all forms of equality, and that includes embracing feminist values.