This guest re-post written by Reginée Ceaser appears as part of our theme week on Ladies of the 1980s.

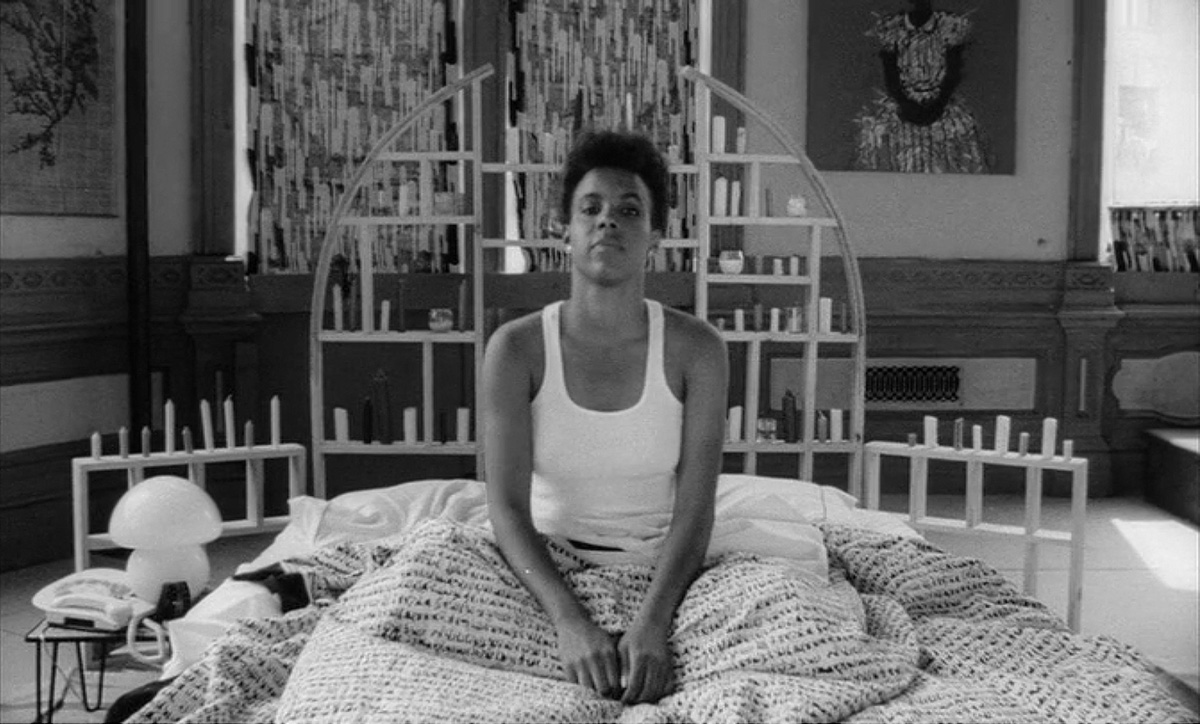

When I was not quite a teenager, I watched Spike Lee’s movie entitled She’s Gotta Have It. I watched and enjoyed the characters’ monologues and the way Spike Lee’s character, Mars, repeated questions during conversation. I knew it was about a young woman who had three boyfriends but did not understand much else, let alone its importance in the framing of the sexuality of Black women. Released in 1986, She’s Gotta Have It chronicled Nola Darling balancing a relationship with three different men at the same. The three men know about each other and constantly vie for Nola’s attention and affections in hopes of being the one she chooses to have a monogamous relationship with.

An issue brought up in the film between the men is maybe Nola is being a “freak” because she’s lacking something emotionally (like daddy issues). The remedy to attempt this “freak” behavior is make Nola go to therapy to work out her issues. Her therapist, a Black woman, feels that Nola does not have the deep emotional issues originally perceived, and is enjoying her healthy sex drive. Satisfied that she’s had enough therapy, Nola continues her relationships with her suitors. Looking back on the film today, I appreciate this film now because it centers on a Black woman who unabashedly is exploring and thoroughly enjoying her sexuality. By doing this, Spike Lee took long held beliefs and perceptions of Black women and pushed back on the constrictions and perceptions of society. Films like She’s Gotta Have It come out few and far between due to the “sensitive” context.

Preconceived notions of Black women in society have permeated into the fabrics of the stories of Black women in film and television creating flat, one-dimensional characters that are forced to speak to the humanity and womanhood of all Black women. Black women characters have been defined for decades by barely developed characters to serve their “larger than life” trope. For instance, there is the angry Black woman, the sassy Black woman, the fat and sassy Black woman, as well as the fat Black woman with low self-esteem, and the fat Black woman that desperately wants the love of a man but in the end is humiliated by him. There is also the frigid Black woman or the hypersexual Black woman. Lastly, and an all-time favorite, the Black woman that must choose between having a career or having a man (read: a dependable, steady sex life) to be fulfilled.

Many stories regarding Black womanhood are deeply rooted in sex and the respectability of sexual behavior projected upon them. Black women are often forced to live in a very tiny box with huge expectations of them and anything less than is being a renegade and a menace to society. We are supposed to be high achievers, while wearing our skirts to our ankles and necklines to our chins. Sex before marriage is frowned upon, having sex outside of a serious relationship can garner side-eyes and distance from friends, and having the audacity to freely explore sexuality outside of the norms of committed relationships and marriage is a disownable offense. There is no gray area allowed, no progression of full womanhood to be pursued and any open, honest conversation about sex and sexuality of Black women is relegated to girls’ night with friends.

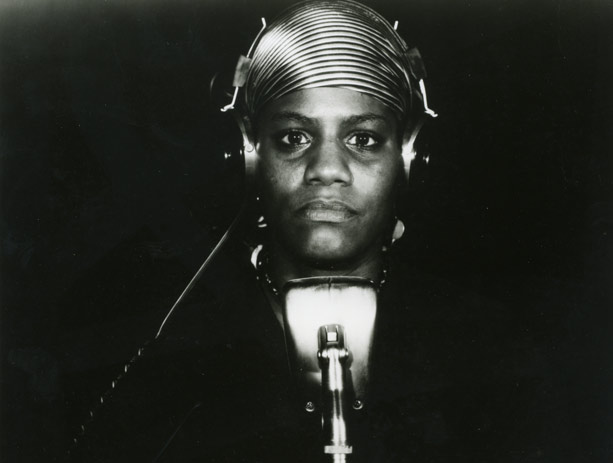

Fast forward to 2013, and Mara Brock Akil debuts a new scripted drama, Being Mary Jane, centering on a Black journalist named Mary Jane, portrayed by Gabrielle Union. I fell in love with Being Mary Jane when Mary Jane sat her in office and masturbated with the help of a mini vibrator before going on a date. Another aspect that I loved about the scene is that Mary Jane didn’t immediately turn to porn to aid in her arousal; she had a computer and a smartphone and yet depended on herself and the vibrator. It is a choice that audaciously and efficiently wrestled down and shattered the myth that only way Black women achieve sexual pleasure is through men. It was gratifying to watch a long-held belief of Black women being scared, frigid and afraid to touch themselves and love themselves sexually evaporate on prime-time television.

Mara also crafted a nuanced woman that balanced a progressing career, taking care of family, evaluating and redefining friendships and of course, navigating an intricate and messy personal life. With Mary Jane’s intricate and messy personal life, Mara takes another bold opportunity to rebuff sexual respectability and cement agency and consent by introducing Mary Jane’s friend with benefits.

Friends with benefits is a subject that is frequently discussed but is tap danced around to avoid being labeled as promiscuous and “loose.” Also hinging on that fear is the thought of losing control of the ability to just have sex with no other emotional attachment. Mary Jane’s friend with benefits, or Cutty Buddy as he is affectionately known by fans, is paramount because he represents more than just surface level sex. He’s a beautiful, muscular, handsome man with a voice that sounds like hot butter on a fresh oven biscuit. He respects her and even cares for her but is fully aware of their agreement, makes no illusions about it, and is committed to upholding it. There is a mutual understanding and reciprocation of attraction that is delightful to see play out. That reciprocation is exciting to see, because too often we see or read about men who have casual sex or play the role of friend with benefits and then immediately degrade and shun them for engaging in sex outside of societal norms of a relationship. For example, in She’s Gotta Have It, Nola Darling did choose a man to have a monogamous relationship with and he in turn verbally attacks her and sexually assaults her for making him feel used. It is the ultimate act of “punishment” that is unfortunately used when sex isn’t played by the rules.

Navigating womanhood is not a straight shot; it’s not perfect but the chance to develop and nurture it on one’s own terms is a perfect realization in the feminist school of thought. Being Mary Jane provides the dialogue and the safety net in saying out loud ,”I see you, I’ve been there too and you are not alone.” The embracing of positive sexuality of Black women on television is not progressive feminism. It is the hope that future depictions of such will not be labeled progressive, but just as common as the stereotypes that have lingered for too long.

Reginée Ceaser is a New Orleans native who is a rockstar in her daydreams, retired daytime soap opera viewer, and proud television binger. Reginée can also be found giving dazzling commentary on Twitter @Skiperella and on her blog, Skiperella.com