Written by Leigh Kolb.

Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs turned 20 this year, and was re-released in select theaters on Tuesday, Dec. 4.

In the introductory interviews that preceded the feature film, actor Eli Roth said that what was most powerful to him in Reservoir Dogs was that “Everybody had a voice.”

Discerning viewers may, at this point, remember that there are no women who have voices in the film. Women are talked about at length, but aren’t players in the film.

However, by analyzing these discussions about women and looking closer at the masculinity of the characters, one can certainly come to the conclusion that Tarantino has a nuanced view of gender and is a feminist filmmaker.

In the opening diner scene, the men are discussing the true meaning of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin.” Most of the men reflect upon their varying degrees of fandom for Madonna. Mr. Brown delivers a brutally vivid description about how he thinks the song is all about a big dick (“dick, dick, dick, dick, dick…”) and making a woman who has had a lot of sex feel like she’s having sex for the first time again. While the language is crass, there’s no clear judgment of the woman in question, or applause for the well-endowed man. It’s just a song analysis.

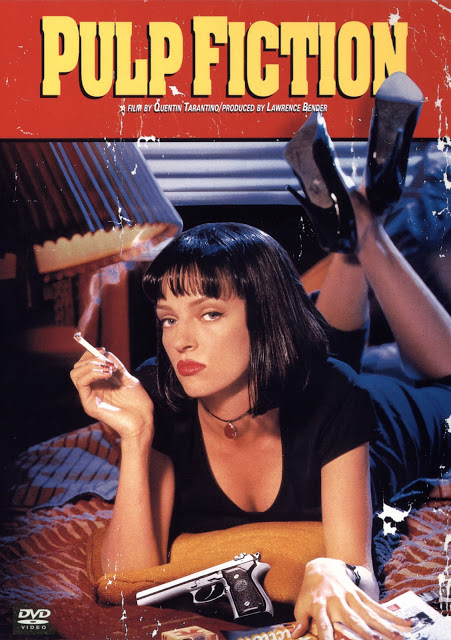

|

| The diner conversations illuminate misunderstanding of and respect or disrespect for women. |

At the very least, the topic Tarantino chooses to open his film with is intriguing. Their understanding, or misunderstanding, of women shows up again a few minutes later, when Eddie brings up K-Billy’s Super Songs of the 70s, and the fact that he’d never realized that in “The Nights the Lights Went Out in Georgia,” the female narrator is the one who kills Andy. Again, they analyze and comment on song lyrics that are sung by women and center around a woman. They are–on some level–interested in understanding women.

The tipping scene at the diner is integral in showing the audience how we are supposed to feel about certain characters. When Mr. Pink adamantly refuses to tip, and goes on a tirade against tipping, Mr. White says:

“These people bust their ass. This is a hard job… Waitressing is the number-one occupation for female non-college graduates in this country. It’s the one job basically any woman can get and make a living on. The reason is because of their tips.”

“Fuck all that,” Mr. Pink says, later adding that “This non-college bullshit, I got two words for that: Learn to fuckin’ type.”

A few minutes into the film, we think that Mr. Pink is an asshole and Mr. White is compassionate. And we’re right. The characters have been shaped during this exposition by their thoughts about women. The less they respect and understand women, the less we are supposed to respect them.

Mr. Orange gets shot when he attempts to carjack a woman (“Who’d have fuckin’ thought that?” he cries, while bleeding in the back of Mr. White’s car) and she shoots him. He then kills her. His instinct is to think the woman in the vehicle is helpless and would be easily overtaken, but he was wrong.

There are various scenes during flashbacks that further explore issues of women and femininity. Mr. White tells Joe that he and his former partner, Alabama, split up due to tensions of pushing “that woman-man thing to far,” but he also adds that she was a really good thief. Mr. Orange (an undercover cop mentored by a black man) concocts a story in which a woman is his drug dealer. Mr. Pink whines about the feminine moniker assigned to him (“It sounds like Mr. Pussy”). Mr. Blonde and Eddie wrestle and spar, showcasing their over-hyped masculinity and their different stations (Mr. Blonde having just been released from prison, and Eddie being the coddled son of Joe, the boss). Mr. Pink’s simplistic views on black women and white women leads Eddie to delve into a story about a cocktail waitress who glued her abusive husband’s penis to his stomach.

The women in Reservoir Dogs exist almost completely off screen, but they wield power in their stories (and literally in their actions, in the case of the woman who shoots Mr. Orange).

Originally, Tarantino had a female police officer briefly appear in the film (this scene is on a special edition DVD extras disc). The absence of female characters doesn’t make the film anti-feminist, though (in fact, considering Tarantino’s treatment of most of his police officers, a female cop may not have done much for the feminist argument).

Reservoir Dogs is not just a violent film about a diamond heist-gone-bad. And while its discussion of women helps the audience to navigate the characters, what makes this film truly feminist is its deconstruction of masculinity.

Mr. Orange and Mr. White, however, both embody the most stereotypically feminine traits of their colleagues. Mr. White is the nurturer, and Mr. Orange the child, pleading for Mr. White to “hold” him and take care of him. They both share vulnerability, their names and are physically close and intimate. They cry together.

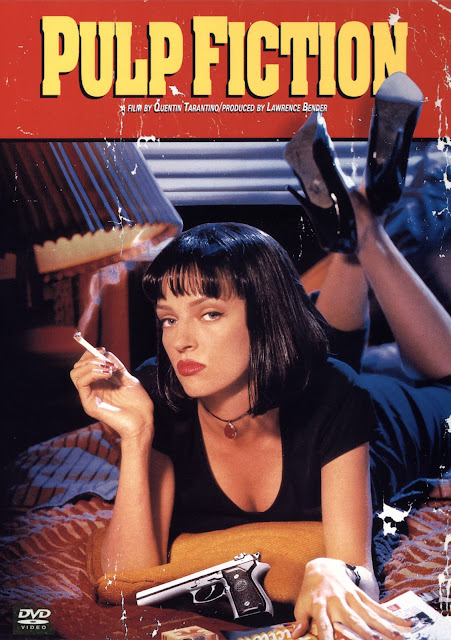

|

| Mr. White comforts and nurtures Mr. Orange. He is heroic because of this. |

In one of the final scenes where Joe, Eddie and Mr. White are in a triangular stand-off. This shot in itself provides interesting commentary on traditional masculinity and the threat that deviations prove to be to those in charge. Eddie is protecting his “Daddy,” Joe is protecting his patriarchal business and Mr. White is protecting Mr. Orange. Mr. White (“Mr. Fucking Compassion,” Eddie calls him) is the most empathetic and kind, and he wins that battle.

|

| From left, Eddie, Joe, Mr. White and Mr. Orange. |

And while no one wins in the end, Mr. Orange and Mr. White come the closest. They survive the longest (if we agree that Mr. Pink is shot as he escapes), and if the audience sees anyone in this film as heroic, it is them. As the cops are coming into the warehouse, Mr. Orange tells Mr. White that he is an undercover cop, and Mr. White is clearly devastated, and pained when he goes to kill Mr. Orange (which his professional code dictates that he must).

The peripheral value of women and the value of the feminine provide a strong, feminist subtext to Reservoir Dogs.

Before the Dec. 4 screening, there were the aforementioned interviews, and there were also previews hand-picked from Tarantino’s collection: Mean Streets; Mother, Jugs & Speed and The Duellists. Harvey Keitel (Mr. White) is in all of these films.

When Tarantino and his friend and producer, Lawrence Bender, were starting the process of making Reservoir Dogs, they were asked who their top choice would be if anyone in the world would be in the film. They answered with “Keitel,” although they realized that would never happen. Bender’s acting coach knew that his wife, Lily Parker, worked with Keitel at the Actor’s Studio, so they gave her a script. Parker loved it, so she gave it to Keitel, and he was on board.

Between Parker’s power and the incredible contributions of Tarantino’s long-time editor, Sally Menke (she worked with him until her death in 2010), one could go so far as to say that Reservoir Dogs as we know it exists because of women.

In any case, feminists should not shy away from Tarantino’s work (even if we can’t sufficiently answer

whether or not Tarantino is a feminist–which I believe he is); instead, we should note the power of the women in his films (as

Bitch Flicks has in the past), the power of the women who are

not in his films, the power of the women who make his films happen and the power of deconstructing and commenting on American masculinity.

—

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.