|

| Before Midnight movie poster |

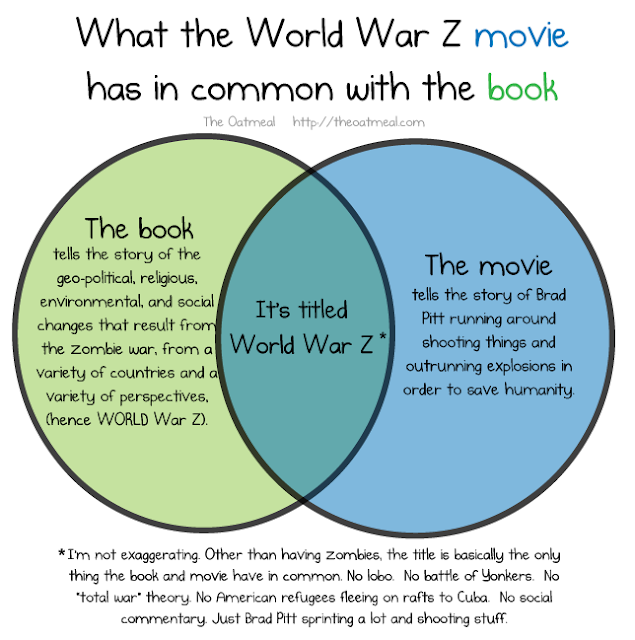

There are numerous reasons why Before Midnight—the third film in the Richard Linklater Before Sunrise/Before Sunset trilogy—is an important film.

|

| Jesse and Celine in Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, and Before Midnight |

It’s an important film first and foremost because it’s a film about grown-ups doing grown-up things. The main characters—Celine (played by Julie Delpy) and Jesse (played by Ethan Hawke)—are in their forties raising two kids together, so the film revolves around the kind of issues such people face: how to be good parents, how to balance the needs of their careers, how to keep the spark alive in their relationship, how to deal with the aging process, etc.

|

| Celine, Jesse, and daughters in the car |

Thankfully the film doesn’t ever give into the gross-out humor that seems to almost be a requirement now for other movies about middle-age—This Is 40, Funny People, and Bridesmaids come to mind (as if moviegoers won’t see a movie that doesn’t have at least one fart joke or an explosion).

|

| Movie poster for This Is 40 |

Before Midnight—like its predecessors—is also important because of its focus on character development, writing, and acting. This is because, thankfully, the major players and co-writers—Linklater, Delpy, and Hawke—believe in creating art that is both realistic and thoughtful. It seems obvious that the three of them want viewers to walk out of the theater asking relevant philosophical questions about both themselves and the characters, a goal which on its own makes these films admirable.

|

| Jesse and Celine holding hands |

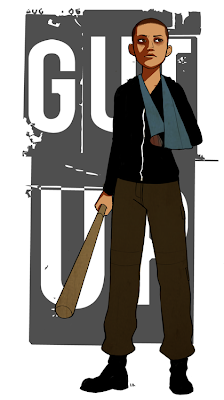

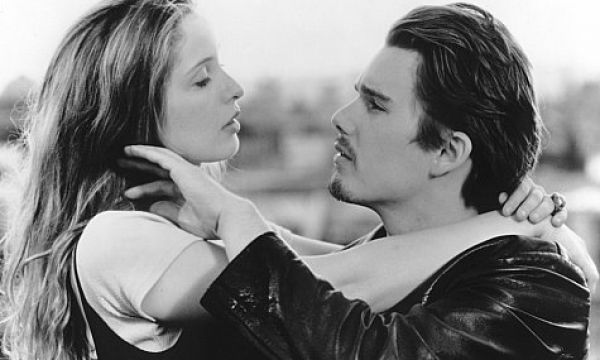

Further demonstrating its importance is the fact that, unlike almost every other movie made today, the characters in this film look real. Sure, when the first film in the trilogy—Before Sunrise—came out, these actors had movie star faces and bodies:

|

| Jesse and Celine in Before Sunrise |

But by now they look like regular people:

|

| Jesse and Celine in Before Midnight |

Celine has fleshy arms, big hips, thick thighs, and a bit of a stomach while Jesse’s age shows in his drawn face, his lined forehead, and the countless wrinkles around his eyes and mouth. Neither of these actors is likely to be cast in the part of the leading woman or man in a Hollywood film, but it’s their so-called flaws that make them so interesting and, in the case of Celine, so beautiful and such an inspiration. If more actresses looked like Celine, then maybe American women would finally learn to give up the notion that they must be thin to be attractive.

|

| Jesse and Celine in Before Midnight |

But for all of its accomplishments, there is a major problem at the heart of Before Midnight, and that problem is that Celine’s character is no longer believable or even entirely empathetic. This is in contrast to Before Sunrise and Before Sunset, where both Celine and Jesse are depicted as the most likeable and well-rounded liberals on the planet.

|

| Celine and Jesse |

In all three of the films, Celine’s feminism is a central focus of the story: she talks to Jesse about her desire to have her own life, her own ideas, and to not be defined by a man. And in Before Sunset and Before Sunrise, she expresses a desire to fall in love and share her life with a man in a committed relationship. In that way, Celine is a wonderful depiction of a modern heterosexual feminist, something we don’t see often enough on the big (or little) screen.

|

| Celine and Jesse arguing in the car |

But in Before Midnight, Celine’s feminism pushes her to behave in ways we’ve not seen her do before—she seems much more hostile and much less empathetic toward Jesse even though he has supported her values and her career throughout their nine-year relationship.

|

| Celine and daughters |

This is especially surprising given that in the first two films, Celine and Jesse agree about gender roles and feminist issues. But in Before Midnight they fight about it from start to finish—even though Jesse agrees with all of Celine’s ideals, making Celine’s depiction unrealistic and troubling.

This problem manifests itself in the following ways: *SPOILERS AHEAD*

1) Celine demonstrates no empathy for Jesse when he expresses regret after they drop off his son at the airport at the end of the summer so he can return home to his mother in the U.S.

Later Celine claims that Jesse is always moody after his son leaves, so it’s surprising that she isn’t more empathetic in this situation. Isn’t that what people do in a healthy relationship? Anticipate each other’s struggles and help them through it? This is just the first example of the ways that Celine acts as if they are in an unhealthy or unhappy relationship even though there are no other signs that they are.

2) Instead of being empathetic in that moment, Celine picks a fight with Jesse, insisting that he wants her to give up her career and move to the States even though he doesn’t ever say that he does.

It would have been so much more interesting for them to have a real discussion about this issue since that’s what healthy couples usually do in these types of impossible situations—acknowledge the difficulty of it, weigh the pros and cons over a period of time, and then make a decision. But Celine seems to see Jesse as incapable of compromising or working with her even though he has evidently done so in the past.

3) She won’t consider moving to the U.S., so Jesse can live near his son even though he moved to France so she could be near her mother when giving birth to their twin daughters.

Not only won’t she move, she doesn’t even want to talk about moving. Her resistance to merely discussing the idea seems strange simply because he has moved for her in the past, and again a healthy relationship between two intelligent adults often requires both of them to put the other’s career first at different times.

4) Celine brings up their problems in front of others at dinner.

There’s not much to say about this except that it’s such an immature move that it doesn’t fit at all with what we already know about Celine, a successful, intelligent, confident woman.

5) She offers little support when Jesse’s grandmother dies.

Not only does she change the subject pretty quickly, but she also declines to go to the funeral when he asks her to do so.

6) Celine implies Jesse was only drawn to her for superficial reasons.

At one point Celine asks Jesse if he would still want her to spend the day with him if he saw her on a train today. It’s a ridiculous question considering how beautiful and intelligent Celine is, especially given that Jesse hasn’t aged as well as she has, a fact acknowledged by Jesse when he says, “The real question is would you want to get off the train with me.” As a result, her question seems to imply that he—and all men by extension—are only attracted to young women and could not possibly find a forty-year-old woman attractive, an idea that may be believable in Hollywood but doesn’t hold water in the world Linklater has created for Celine and Jesse.

7) She resents his career and does so while simultaneously asking him to respect hers.

This resentment is demonstrated when she complains about their trip to Greece to spend time with another author, when she is reluctant to autograph Jesse’s books for a fan in their hotel (even though the books are about her), and when she insists he is never allowed to write about her again. It’s hard to believe that a true feminist—like the Celine we have come to know and love in the earlier films—would indulge in this kind of hypocritical behavior.

8) She holds Jesse responsible for all of her problems with men and the patriarchal society we live in.

She does this even though he’s proven he’s not that kind of guy and understands she’s not the kind of woman who would put up with that kind of man, explaining, “You could never be submissive to anybody.”

9) Finally, this problem comes to an ugly head when Celine tells Jesse—at the height of their argument about their future—that she doesn’t think she loves him anymore and then walks out on him.

It’s a cruel thing to say even if she does mean it, but the fact that Jesse doesn’t take it seriously and they make up leads the viewer to believe that she doesn’t even mean it and has possibly even said—or insinuated it—before. In that sense, it feels like she is playing a game with him, a dangerous childish game that is the adult equivalent of sticking your tongue out at someone. It’s a moment when Celine shows no respect for Jesse’s feelings, and viewers are left to wonder how she can expect him to respect her if she doesn’t do the same for him.

******

Because other aspects of this film—including acting and characterization—are so strong, I can only conclude that these problems with Celine are the result of bad writing. It’s certainly true that the writing in Before Midnight lacks the subtlety and complexity evident in the first two films.

Good writing demands well-rounded characters, but Celine seems more flat and one-dimensional in this film than she ever has before. Jesse’s flaws are rather ordinary—he doesn’t like to clean the house, and he has stubbornly held onto his slacker facial hair. But Celine’s flaws are the opposite of ordinary—rather than being average, they are so extreme in the third film that they don’t even seem believable given what else we know about her character. If she’s an educated, intelligent, confident, and strong woman, why doesn’t she trust the man who loves these things about her?

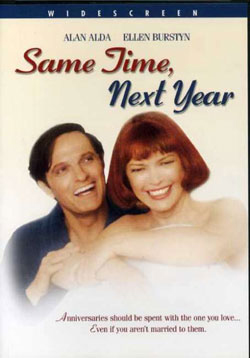

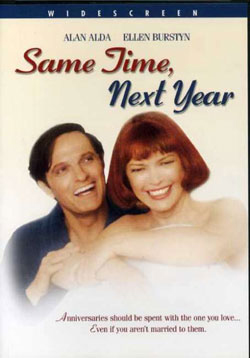

Though they haven’t done it before, Linklater, Delpy, and Hawke fall back on stereotypical ideas about what it means to be a feminist when writing Celine’s dialogue for this film. They make her seem harsh and narrow-minded—even irrational at times—rather than thoughtful and open-minded. In this way, the film harkens back to another well-known “talky” film about a heterosexual couple discussing important issues, 1978’s Same Time, Next Year.

|

| Movie poster for Same Time, Next Year |

Unfortunately it feels like Before Midnight also co-opted that film’s take on intelligent couples by merely showing them in constant disagreement. It’s a depiction that feels outdated given what we know by now about communication in healthy, equitable relationships.

This seems to be an honest mistake, but it’s a disappointing one nonetheless, especially since it’s so hard to find movies about strong feminists and because the two previous films sidestepped these landmines so well by making Celine both willful and caring.

In fact, by depicting strong, intelligent women as incapable of compromise and empathy, Before Midnight reinforces all of the ugly stereotypes about feminists and sends the message that you can’t be a good feminist if you stay home with the kids or sew curtains or move for your spouse. When in reality, feminists—female and male alike—can do all of the above since feminism isn’t about acting a certain way but rather about embracing equality.

This misrepresentation is alluded to when Celine says to Jesse, “I feel close to you… But sometimes, I don’t know? I feel like you’re breathing helium and I’m breathing oxygen.”

It’s this comment that best sums up the problems with the film because it implies that men and women are reduced simply to their differences and that they are, in fact, so different that they cannot possibly relate, agree, compromise, or even get along past a certain point in their relationship. It’s a rehashing of the old men-are-from-Mars-women-are-from-Venus idea that is anti-feminist and unbelievable as well as being one that this viewer found very difficult to relate to.