Written by Leigh Kolb

As press began trickling out about The Counselor, headlines about how “Cameron Diaz fucks a car” (a Ferrari) dominated my news feeds.

I did not expect that scene to be brilliant. But it kind of was.

The Counselor is by no means the “worst movie ever made.” The writing–Cormac McCarthy’s first screenplay venture–was lovely, if at times a bit much (as one might imagine a script by a novelist would be). The acting was incredible. Ridley Scott’s direction is poignant. This also isn’t the best film ever made, but it has enough strong points.

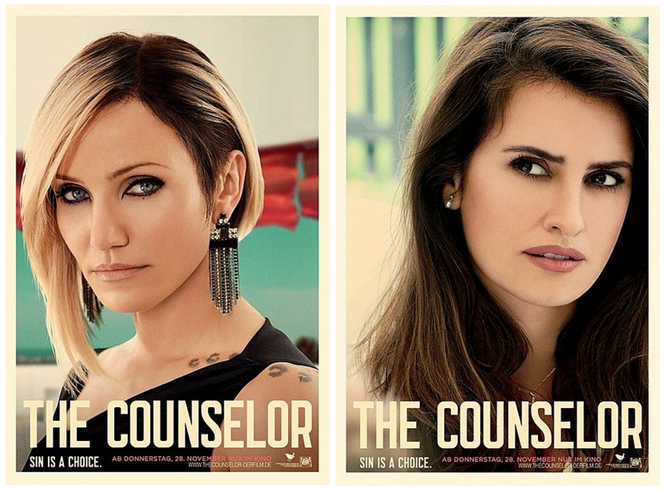

The two prominent women characters did fit into the problematic virgin/whore dichotomy, but overall I was surprisingly pleased at the depictions of female sexuality on screen, and the larger meaning of those scenes.

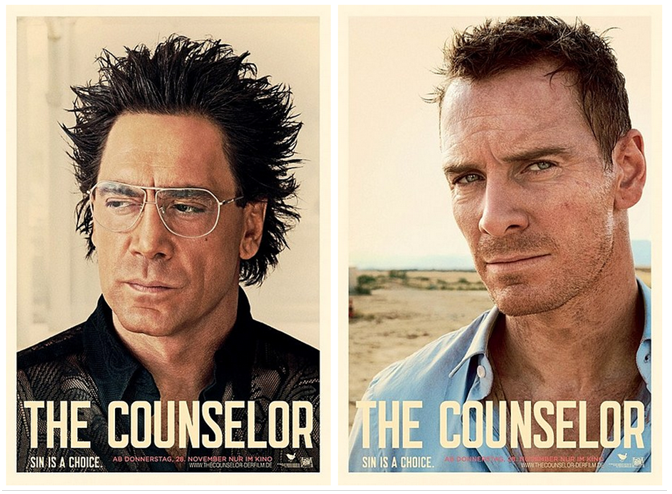

The opening scene (which The New York Times describes in loving detail) finds the audience in bed with our protagonist, the Counselor (Michael Fassbender) and his soon-to-be fiancée, Laura (Penélope Cruz). Their exchange is intimate, and he wants her to tell him what to do to her. While she’s slightly shy and hesitant, they are comfortable together. He retreats downward to perform oral sex on her, and she orgasms. Enthusiastically.

In the opening scene, we see a focus on female pleasure that is often foreign in heavily masculine films like this. They have just woken up, but he doesn’t want her to “tidy up.” Their white-sheet-wrapped love seems meaningful and real.

The bulk of the film, of course, follows the Counselor (he is nameless; other characters refer to him only in relation to his identity as a lawyer) and his decision to enter into a drug deal to make some fast money. This descent into a different world happens toward the beginning of the film, and what follows is a classic morality play, in which our prince falls, bringing those around him down with him. The dialogue, like the morality play itself, is Shakespearean, which is a bit much for most modern audiences. (There is a lot of talking…)

Hero, moral dilemma, advice from dubious sources, downfall, pile of dead bodies. Yeah, sounds pretty Shakespearean.

The two women characters are also quite Shakespearean with their subtle complexities and clear contrasts, which push us to consider what feminine power is and how we are supposed to judge the characters who surround them by their relationship with women. The Counselor deeply loves Laura and acts baffled when Reiner (Javier Bardem) speaks with disrespect/bawdiness about women. The Counselor loves giving women pleasure. Reiner sees women as dangerous liabilities.

Reiner’s girlfriend–who we meet as she’s riding a horse across the desert with a cheetah by their side–is Malkina (Cameron Diaz). She is certainly a cheetah herself–gorgeous, fast, sleek, frightening, and threatening. Her role is impressive and important.

But about that Ferrari scene.

We see the scene as a flashback while Reiner is talking to the Counselor about something he’d “like to forget.” That something is the time that Malkina fucked his yellow Ferrari.

Malkina is trying really hard. Really hard. She slips off her panties and tells him she’s going to fuck his car. She climbs up on the windshield, descends into the splits, and goes to town right above Reiner’s face.

This scene–in which a gorgeous woman has sex with a luxury automobile to try to be really sexy and get off (on the luxury itself?)–is telling in how absolutely ludicrous it is. Reiner is “stunned”–and it doesn’t seem like he’s stunned in a good way. It’s just ridiculous.

(And OK, Reiner’s “catfish” description from his vantage point was funny–when he talks about the “gynecological” display upon the glass in terms of one of those “bottom feeders you see going up the way of the aquarium sucking its way up the glass,” that just intensifies how stupid the whole thing is.) Variety has the dialogue from that scene.

Malkina’s immorality is essential in this morality story. The power she wields is significant–she’s certainly more malicious and skillful than our leading men. However, we are not supposed to be rooting for Malkina (even though we can find her wiles pretty amazing).

The symbolism of her fucking a Ferrari, and getting off in the process (the Counselor is very interested in whether or not she was able to orgasm), shows us just how materialistic she is. It’s not about human pleasure, it’s about object pleasure.

It’s not about genuine, self-aware female sexuality. It is ridiculous. And Reiner’s description of the fish on the aquarium? That’s exactly what it would look like. So dammit, I think it’s hilarious. The honesty of a man saying, “What the hell was that?” when a woman is trying to do what society expects her to do to be sexy is a pretty clear indication of how our raunch culture makes fools out of women who try to fit into it.

If Reiner had loved it, I think I would have found that scene incredibly Problematic From a Feminist Perspective™. But he didn’t. This otherwise misogynistic character was baffled and troubled by this kind of display.

Laura and Malkina aren’t as fully developed as they probably could have been (early on it’s clear that Laura=good and Malkina=bad when the two are having a conversation and Malkina can give Laura all of the details about Laura’s engagement diamond–and Laura doesn’t even want to know how much it’s worth–and their conversations about sexuality make Malkina seem the whore and Laura seem virginal).

I did appreciate, though, how the women were their age. As disturbing as the marketing for the film was, these women are presented as neither younger than they actually are nor trying to be younger. While they are beautiful, they have wrinkles. While they are sexy, they are not 20. This is refreshing.

The Counselor isn’t the best–or the worst–film ever made. However, its artistic merit as a modern-day morality play and its representation of and commentary about femininity and female sexuality make it stand out.

__________________________________________________________

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.