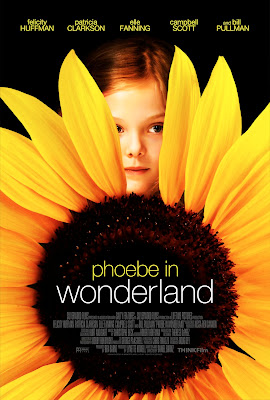

Phoebe in Wonderland. Starring Felicity Huffman, Elle Fanning, Patricia Clarkson, and Bill Pullman. Written and Directed by Daniel Barnz.

For a film that wants to explore the difficulties of marriage and motherhood and, essentially, what it means to exist as a woman in a society that places so many demands on wives and mothers, I found it disconcerting to say the least that this film only barely passes the Bechdel Test. If it weren’t for one scene, where Felicity Huffman’s character, Hillary Lichten, engages in a brief conversation about her daughter, Phoebe, (played by Elle Fanning) with her daughter’s drama teacher, Miss Dodger, (played by Patricia Clarkson), then this entire movie, a movie about women, would plod along without one woman ever speaking to another woman.

imdb plot summary: The movie focuses on an exceptional young girl whose troubling retreat into fantasy draws the concern of both her dejected mother and her unusually perceptive drama teacher. Phoebe is a talented young student who longs to take part in the school production of Alice in Wonderland, but whose bizarre behavior sets her well apart from her carefree classmates.

Well, on the surface, the movie is about Phoebe and her struggle to fit in with her peers. But it quickly turns into an examination of motherhood and parenting in general, when Phoebe’s odd behavior gradually worsens: she spits at classmates, she obsessively repeats words and curses involuntarily, she washes her hands to the point that they bleed—and she explains to her parents over and over again that she can’t help it. However, her mother (and father), being academic writer-types (Hillary is actually attempting to finish her dissertation on Alice in Wonderland), merely choose to see their daughter as nothing more than eccentric and imaginative.

The caretaker r ole falls exclusively to Hillary. She’s a stay-at-home mom trying to write a book while also attempting to care for two young daughters. While her struggle to play The Good Mom definitely lends sympathy to her character—I mean, honestly, what the hell is a good mom?—I couldn’t help but despise her selfishness and blatant disregard for Phoebe’s needs. Even though both parents decide to (finally) get Phoebe into therapy, it’s Hillary who refuses to accept the doctor’s diagnosis, even going so far as to remove Phoebe from therapy, deliberately hiding the diagnosis from her husband.

ole falls exclusively to Hillary. She’s a stay-at-home mom trying to write a book while also attempting to care for two young daughters. While her struggle to play The Good Mom definitely lends sympathy to her character—I mean, honestly, what the hell is a good mom?—I couldn’t help but despise her selfishness and blatant disregard for Phoebe’s needs. Even though both parents decide to (finally) get Phoebe into therapy, it’s Hillary who refuses to accept the doctor’s diagnosis, even going so far as to remove Phoebe from therapy, deliberately hiding the diagnosis from her husband.

The problem here, and where the movie most succeeds, is that Hillary feels alone as a parent. She believes that her children’s struggles will ultimately reflect poorly on her as The Good Mom, and she even says at one point that she doesn’t want her daughter to be “less than.” Obviously, we live in a society that mandates the over-the-top importance of living up to an unattainable standard of proper mothering (see: any celebrity mother and the scrutiny she faces, with barely a mention of celebrity fathers), and Hillary definitely effectively represents that unattainable standard.

The movie also  successfully portrays the societal trend of the working father: he pokes his head in when necessary, checking in on his daughters, and demonstrating just the right balance between quirky annoyance at their neediness and curiosity about their daily lives—he shows up to parent/teacher conferences, he consoles Phoebe when she gets in trouble at school, and he genuinely wants to participate; he’s just not required to maintain the role of The Good Dad—it doesn’t exist.

successfully portrays the societal trend of the working father: he pokes his head in when necessary, checking in on his daughters, and demonstrating just the right balance between quirky annoyance at their neediness and curiosity about their daily lives—he shows up to parent/teacher conferences, he consoles Phoebe when she gets in trouble at school, and he genuinely wants to participate; he’s just not required to maintain the role of The Good Dad—it doesn’t exist.

In many ways, Miss Dodger, the drama teacher, saves Phoebe from herself, at  least for a while. Clarkson’s character complicates the film further by positioning Miss Dodger as somewhat of an Other Mother—they’re kindred spirits, and Miss Dodger attempts to create a safe space for Phoebe in the theater, realizing that she doesn’t feel safe anywhere else. But in the one main interaction between Hillary and Miss Dodger, Hillary confronts Miss Dodger about Phoebe’s penchant for self-injury, even blaming her for not paying close enough attention (which is nothing more than a projection of Hillary’s own feelings about failing at the role of The Good Mom).

least for a while. Clarkson’s character complicates the film further by positioning Miss Dodger as somewhat of an Other Mother—they’re kindred spirits, and Miss Dodger attempts to create a safe space for Phoebe in the theater, realizing that she doesn’t feel safe anywhere else. But in the one main interaction between Hillary and Miss Dodger, Hillary confronts Miss Dodger about Phoebe’s penchant for self-injury, even blaming her for not paying close enough attention (which is nothing more than a projection of Hillary’s own feelings about failing at the role of The Good Mom).

At first, the film explores Hillary’s inability to separate the weaknesses she perceives in her children from her (real or imagined) personal failings as a mother. And that theme deserves recognition. Hillary is a complicated character, after all, and how often do we get to watch complicated women struggle with real issues on-screen? The issue I struggle with, though, warrants discussion as well: how long does Phoebe have to repeatedly self-harm before her mother acknowledges the doctor’s diagnosis?

What could’ve been (and actually was, at first) a feminist investigation of the plight of motherhood and marriage in a society that still treats women as second-class citizens (even if it pretends not to view th em as such), somehow turned into an indictment of The Selfish Mother. Just because Hillary says out loud (something along the lines of): “I don’t want to look at my life when I’m 70 and realize I did nothing important. But at the same time, I wouldn’t mind. My daughters make me live,” well, that doesn’t negate the fact that she waited until her daughter jumped off a fucking theater scaffold before she decided that, okay, something might be wrong with her.

em as such), somehow turned into an indictment of The Selfish Mother. Just because Hillary says out loud (something along the lines of): “I don’t want to look at my life when I’m 70 and realize I did nothing important. But at the same time, I wouldn’t mind. My daughters make me live,” well, that doesn’t negate the fact that she waited until her daughter jumped off a fucking theater scaffold before she decided that, okay, something might be wrong with her.

The film makes it almost impossible not to hate that mother: in one scene, she comforts Phoebe after a nightmare, realizes Phoebe has horrible bruises all over her legs, and listens (once again) to Phoebe cry about how she can’t help hurting herself. While Phoebe continues her obsessive compulsions, which result in removal from the play at one point, her mother continues to ignore the doctor’s diagnosis of Tourette’s Syndrome.

My point is, what the fuck? Am I supposed to believe that part of the feminist co mplications of motherhood include the struggle to not seriously neglect (and consequently, abuse) your child? Perhaps in some warped way, the film wants to illustrate how motherhood in our society really is a double-edged sword: she can choose to help her daughter, and risk feeling like a failure as a mother (because she would have to acknowledge her daughter is “less than”), or she can hope that her child really is an imaginative eccentric who shouldn’t be medicated and drained of her creativity.

mplications of motherhood include the struggle to not seriously neglect (and consequently, abuse) your child? Perhaps in some warped way, the film wants to illustrate how motherhood in our society really is a double-edged sword: she can choose to help her daughter, and risk feeling like a failure as a mother (because she would have to acknowledge her daughter is “less than”), or she can hope that her child really is an imaginative eccentric who shouldn’t be medicated and drained of her creativity.

While Hillary clearly buys in to both the cult of motherhood and the demonization of disability, the filmmakers really only succeed in showcasing the latter, resulting in a somewhat interesting examination of how we, as a society, often react to what we perceive as different or Other. But because the film also attempts to examine motherhood simultaneously, I found it virtually impossible not to read it as anything more than a deliberate, over-the-top, worst case scenario metaphor for the consequences of Bad Mothering.

into an early scene of near-rape played for laughs as well. One of the successful DJs, feeling sympathetic toward a younger man because of his virginity, tries to trick his date for the night into having sex with the other man while the lights are turned off. He hopes that she won’t notice the switch, in spite of a huge size differential between the two men. The scene is played entirely from their perspective, and while the younger man doesn’t get near enough to the woman to touch her, there is a “ho ho ho, so funny my sides might split” scene in which the lights unexpectedly go on, and she screams as she finds herself alone in a room with a naked stranger. I was left with a queasy feeling at the end of that scene, wondering if this was what the whole movie would be.

into an early scene of near-rape played for laughs as well. One of the successful DJs, feeling sympathetic toward a younger man because of his virginity, tries to trick his date for the night into having sex with the other man while the lights are turned off. He hopes that she won’t notice the switch, in spite of a huge size differential between the two men. The scene is played entirely from their perspective, and while the younger man doesn’t get near enough to the woman to touch her, there is a “ho ho ho, so funny my sides might split” scene in which the lights unexpectedly go on, and she screams as she finds herself alone in a room with a naked stranger. I was left with a queasy feeling at the end of that scene, wondering if this was what the whole movie would be.  or a man to find a condom, ends up sleeping with someone more famous because she finds him impressive. Another comes onboard to marry one DJ, without telling him that she’s only doing it in order to sleep with someone else on the ship. I can imagine the first case happening in real life: When women have sexual agency they will sometimes decide to sleep with someone other than the person they start out an evening with. I can’t imagine a context for the inexplicable cruelty of the second case though, and since she represents roughly one quarter of all women in this film, it is easy to assume that the film is endorsing the idea that all relationships with women are suspect, and only relationships between men are noble and pure.

or a man to find a condom, ends up sleeping with someone more famous because she finds him impressive. Another comes onboard to marry one DJ, without telling him that she’s only doing it in order to sleep with someone else on the ship. I can imagine the first case happening in real life: When women have sexual agency they will sometimes decide to sleep with someone other than the person they start out an evening with. I can’t imagine a context for the inexplicable cruelty of the second case though, and since she represents roughly one quarter of all women in this film, it is easy to assume that the film is endorsing the idea that all relationships with women are suspect, and only relationships between men are noble and pure.  with my husband after the film, and pointed out that most women perceive themselves as the protagonists of their own lives, not as an avid audience for men as they play out their stories. My experience throughout my life when watching movies like this has been to desperately try to find a place for myself among the male characters. How can I be Phillip Seymour Hoffman? There is no space for women in this movie, so how do I rewrite the movie so I can fit myself in? I’ve been doing it for so long that it is almost natural to me, but I think it’s time that it stopped.

with my husband after the film, and pointed out that most women perceive themselves as the protagonists of their own lives, not as an avid audience for men as they play out their stories. My experience throughout my life when watching movies like this has been to desperately try to find a place for myself among the male characters. How can I be Phillip Seymour Hoffman? There is no space for women in this movie, so how do I rewrite the movie so I can fit myself in? I’ve been doing it for so long that it is almost natural to me, but I think it’s time that it stopped.