This guest post by Rosie Kar appears as part of our theme week on Asian Womanhood in Pop Culture.

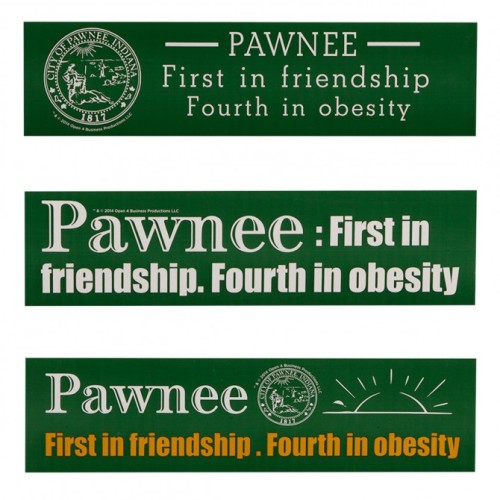

In fall 2009, CBS premiered its Sunday evening courtroom drama, The Good Wife. Currently on its fourth season, the show and its cast has garnered numerous awards, including Golden Globes, Emmys, Peabody Awards, Screen Actors Guild awards, and Television Critics Association awards, among others. The premise of the show came about after producer Michelle King took note of the number of American politicians embroiled in very public sex scandals, and their wives standing beside them. Bill Clinton, Eliot Spitzer, John Edwards, and Rod Blagojevich, among countless others, were engaged in fraudulent activity while in office, often having extramarital affairs with stoic wives beside them in public appearances.

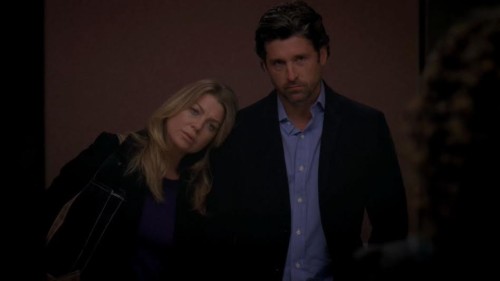

In The Good Wife, Alicia Florrick, played by Julianna Margulies, is an associate attorney at Lockhart and Gardner, returning to a corporate environment after fifteen years of staying at home and raising two children. Her husband is Peter Florrick, disgraced State’s Attorney, who was put in prison on charges of political corruption, as well as engaging in extramarital sexual affairs with sex workers. The narrative of the series is centered on Alicia, and the ways in which she navigates being in the storm’s eye of scandal, working as the sole breadwinner for a time to support herself and her two children with Peter, and rising up the career ranks at the firm.

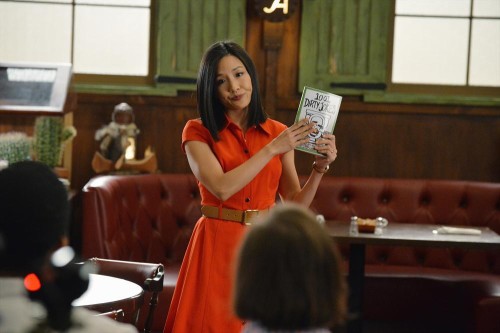

Driven by compelling story arcs and strong performances by ensemble cast members, The Good Wife has been hailed as one of the best dramas on television. Though based in downtown Chicago, there is a paucity of people of color in the show, and those who do make appearances seem to be present for only short amounts of time, save for one: Kalinda Sharma. She is an independent private investigator for the firm Lockhart and Gardner, and is a supporting character in the series’ narrative. Played by actress Archie Panjabi, the role of Kalinda Sharma is one that is groundbreaking in terms of thinking about queer South Asian bodies onscreen in the American imaginary. Television shows us what is happening and recodes what is in the popular, transmitting it into the home for consumption. Kalinda Sharma performs the behavior of civilized productivity, but her styling as a queer figure seeks to trouble heteronormative, heteropatriarchal notions of stability. Kalinda does not conform to what Jasbir Puar terms the assemblage of the “monster-terrorist-fag”[1]; but rather, she is a different kind of triangulation: A South Asian American, queer, female. Kalinda is what Eve Oishi determines as a “Bad Asian. Bad as in “badass.” Bad as in anyone…who talks candidly about sex and desire. Bad Asians are inherently threatening to hegemonic systems.”[2]

She is a secondary character, and her narratives take a backseat to larger arcs, but I am proposing that Kalinda embodies a queer uncanniness. This raises uncomfortable and necessary questions and discussions around gender and sexuality within the South Asian American community. Kalinda Sharma is the first and only representation of an openly queer South Asian woman on television in the American public at this time. What are the costs of her representation? What does she do to trouble the American psyche? How does she puncture notions of civilized productivity while simultaneously reinforcing them? How is her power as an American citizen questioned and informed? Kalinda might be an example of what Gayatri Gopinath deems “queer articulations of diaspora as they emerge in the home.” [3] Her darkness signifies Otherness, uncertainty, immigration, and uncertainty, but with it, carries a powerful depth. A standout figure in the series, she is likeable, sarcastic, and beautiful, but she troubles the American Dream, as a powerful, combative, intelligent queer woman of color. Perhaps, most curious of all, she is useful as a commodity to the institutional corporate structure by which she is employed. In spite of her use value, she commands respect, but questions around her sexuality and secretive past are central forces of her narrative arc. She is a dark threat to the safety and security of those around her; as a private investigator, her job is uncovering secrets. Her body, labor, and performances become ways to critique and undercut the various discourses of modesty, sexual morality, and purity that are culturally fixed onto her by hegemonic South Asian diasporic and nationalist ideologies. Kalinda, as an uncanny figure, is inextricably bound up with creative, and generative uncertainties about her sexual identity. She inhabits the role of the detective for hire, a liminal figure that can cross boundaries without question, and the audience is afforded the pleasures of South Asian femininity and beauty being questioned onscreen, with her queerness as fodder for titillation.

Nicholas Royle points to the significance of the relationship between that which is queer and the uncanny, arguing that “the emergence of ‘queer’ as a cultural, philosophical and political phenomenon, at the end of the twentieth century, figures as a formidable example of the contemporary ‘place’ and significance of the uncanny. The uncanny is queer. And the queer is uncanny.”[4]

Kalinda might inhabit the old specter of the tired dragon lady trope, deemed an uncanny sidekick to protagonist and scorned wife, Alicia Florrick. She is known for her knee high vinyl stiletto boots, sharp wit, quick tongue, questionable ethics, and sexual ambiguity. While the audience is not given any specific information about Kalinda’s past, it is treated to snippets of information, and queries about her past have elicited enough interest via social media and blogospheres to warrant her own hashtag on twitter: #KalindasPast. Panjabi’s performances have earned her rave reviews, a prominent place in the series opening credits as part of the main cast, countless nominations and an Emmy Award in 2010, for her role as an “Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series.”

But however productive it may seem to have Kalinda Sharma as a major player in a primetime network drama, there are drawbacks. She is evacuated from her culture, with little to no mention of her identity in any way, and she appears to exist in a racial vacuum In the first season, her ethnic identity is confirmed by a brothel owning madam as “East Indian,” who haughtily inquires about Sharma’s “availability” to work as a sex worker, as the exotic Other was in high demand by the madam’s clientele. In the episode “Mock,” Alicia Florrick must represent one Simran Verma (played by seasoned actress Sarita Chaudhury), a South Asian woman living in the U.S. for 27 years, who may be deported after paying a corrupt lawyer $8,000 to secure a green card that never came through. Requesting Kalinda’s help on the case, Alicia says to Kalinda that she thought she would be more sympathetic to Verma’s situation. Kalinda asks “why? My parents came here legally.” It is revealed that she does not speak Hindi. She states at the end of season two: “I have no friends… and I never have to confide in anybody.” (Season 2, Episode 22: “Getting Off.”)

Friendless Kalinda may serve as a dark double, an uncanny foil to Alicia Florrick, as the troubling queer brown woman. Alicia Florrick is the Georgetown educated, beautiful good white wife, the televisual embodiment of Freud’s “heimlich.” Freud argues that when concerned with works of art, “aesthetics…in general, prefer to concern themselves with what is beautiful, attractive, and sublime, that is with feelings of a positive nature, with the circumstances and the objects that call them forth, rather than with the opposite feelings of unpleasantness and repulsion.”[5] In Freud’s interrogation of the word, the “heimlich” is etymologically rooted in “heim,” or home, but heimlich has a double meaning. The first meaning is related to that which is intimate, familiar, domestic, and comfortable. The second meaning is related to that which is private, secluded, hidden, and elusive. The perspectives are such that while “heimlich” is evocative of a certain privileged perspective, from inside the space of comfort, it is also alluding to the impenetrability of that which is hidden, those places of privacy, security, and secrecy. That which is unheimlich collides with the second meaning of heimlich. Unheimlich then, is descriptive of that which sinister, eerie, strange, and oddly familiar, shoring up images of discomfort. Freud states that the discomfort in the sensing of uncanniness is because what was once familiar has somehow become strange, not because it is new or unfamiliar. He cites Schelling, arguing “unheimlich is that what ought to have remained hidden, but has nonetheless come to light.”[6]

Seemingly “light,” Alicia is inherently likable, a protagonist that is endearing to the audience, who sympathizes with her plight. A scorned, but privileged woman, she struggles to maintain strong and meaningful connections with her children, raising them in the best manner she knows how. She is also forced to play the role of the good wife, performing forgiveness of her husband’s faults, so that he may be re-elected to public office. Forty-something years old, dark haired, pale skinned, classically beautiful, and slender, she is always donned in professional office attire, in shades of black, blue, red, and purple. Her sleeves are long, her collars are tightly buttoned, her skirts are knee length and longer, hiding her body. Alicia’s aesthetics are such that she fits in with hegemonic images of heteronormative, corporate America. With few friends, she is the breadwinner of the Florrick household, slowly inching up her firm’s echelon. Publicly, she has not had any romantic liaisons with anyone than her husband, is mindful of her conduct when appearing in court, as well as beside her husband. We see glimpses of the darknesses that plague Alicia, who always seems to carefully negotiate and navigate her way through life. Alicia is friendly, hospitable, well-liked at work, often seen in domestic arenas, and serves as a peacekeeper, and is a source of comfort. She is also plagued by silent suffering.

We might say that Alicia Florrick, to the American public, embodies both definitions of Freud’s conceptualization of the heimlich. On the one hand, she is “homey,” comforting, likeable, and familiar. On the other hand, she is very much a private person, withholding information. In the dialectical sense of that which is heimlich, Alicia, a middle class, bourgeois subject, can also be understood to be holding information back from herself, her husband, her children, and her public. The only ones privy to her private discomforts are the audience members.

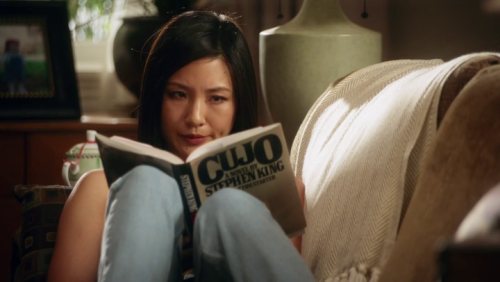

Kalinda Sharma, however, is evocative of the uncanny, she is that “class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.”[7] She may be painted as a djinn, native informant, sexual and racial Other, dark double, collapsed into the body of a queer South Asian American woman. Like Alicia, Kalinda is always dressed in muted but expensive clothing in jewel tones, dark shades of red, blue, purple, green, and black. She wears micromini skirts, leather jackets in every color, and her signature accessories are thigh high black patent leather stiletto boots, and either a bat or a gun, evoking fantasies of a phallus wielding dominatrix.

The camera loves her, drinking in her golden brown skin, black hair, big dark eyes, rimmed in kohl, pouty mouth lipsticked in a vampy shade of maroon. She is a beautiful woman, and the audience is treated to low lit beauty shots when she is onscreen, with her face taking up the entire frame. We often see her in dark places, like underground parking garages, closed offices, and at twilight. Kalinda takes no nonsense from anyone, utilizing her sharp tongue, and will do whatever it takes to get the information she needs for her bosses, no matter the means. Unlike the dark female figures present in narratives by South Asian American authors,[8] Kalinda is already assimilated, as a second generation American. But her aesthetics and behavior are different from the majority.

There is a clear emphasis on how color provokes a sense of her foreignness. She is the opposite of Alicia Florrick, and as such, becomes her best friend, her confidant, and perhaps eventual lover. Kalinda is prone to sarcasm, never fearful of expressing her disdain and reticence for situations, deflecting inquiries about her personal life back onto the offending party. Unlike Alicia Florrick, an outwardly likable character, Kalinda harbors secrets, and is deeply “heartless, insensitive, with self-preservation as [her] number one concern.”[9] as described by a former scorned female lover. While Alicia Florrick is either in her home, at her office, with her children, or alone in her bedroom, Kalinda is, terrifyingly, everywhere as well as nowhere. Her behavior thwarts belonging; she is the “unknown, unfamiliar,… the “unheimlich is the name for everything that ought to have remained secret and hidden but has come to light.” As the highly paid private investigator for Lockhart Gardner, Kalinda’s labor as the unheimlich foil to the protagonist is made manifest in her work. She gets ahold of information that is supposed to be kept secret. Her private life, too, is kept closely guarded, but is inadvertently revealed, week by week, and the secrets that are exposed are unsavory.

Kalinda conjures up the ultimate fantasy of civilized productivity. She is everywhere, has access to information through unknown means, gets coded and classified documents for cases through medical examiners, and has connections to Chicago’s police department. She is often put on surveillance detail, able to observe and record the activities of nefarious characters. Like every good, model South Asian American, she is technologically savvy, performing the role of the Asian geek, hacker, encrypter, decrypter, photographer, and computer programmer. She is something of a superhero, climbing walls, breaking into apartments, obtaining information legally and illegally. She defies proprietary codes of proper female behavior, openly using her sexuality to achieve her goals. She embodies the seductive dragon lady, capable of emasculation, with her gun or baseball bat as a phallus. She may be a secondary character, but Kalinda Sharma has the uncanny ability to tantalize almost everyone in her midst.

Her bosses, colleagues, and informants want to sleep with her, both men and women. Kalinda becomes good friends with Alicia, but the fact that she slept with Alicia’s husband is the penultimate secret that would destroy their relationship, and Kalinda, unsuccessfully, does everything in her power to keep that information private. It is ultimately revealed that she does not differentiate between men and women, choosing instead to be “flexible.” In coded terms, then, Kalinda as the uncanny marks the return of the repressed, that information and behavior that Alicia Florrick cannot engage in.

Kalinda’s “darkness” also functions in terms of specific cultural labor, alluding to discourses around ethnicity and race, which are inextricably intertwined with discussions around citizenship and Americanness. Literary and visual metaphors around darkness are laced with feelings of discomfort around the unknown, impure, threatening, mysterious, and dangerous. Manicheanism deploys binaries sutured with darkness and light, and this tradition of dichotomous thinking still continues. Under the British Raj, a specific kind of temporal aesthetic racialization occurred, and darkness was something to be avoided. Historical prejudices and violences against those having dark skin in South Asia were not sanitized; British and South Asians alike linked darkness with desirability, class, caste, religious ideology, and intersectional privileges. The saying goes, “White is right”; those wanting to capitalize on a supposedly superior class status, as part of the elite, disavowed interactions with subaltern indigenous people.

The discourses around skin color has had lasting legacies, still experienced today, in conversations around beauty, behavior, arranged matrimonial arrangements (where young women are implored to stay out of the sun). There is capital generated by lightening creams like “Fair and Lovely,” or “Fair and Handsome” for the face and most recently, the vaginas, of brown women.[10] Advertisements for marriage in the back pages of South Asian newspapers, as well as websites like Shaadi.com and BharatMatrimony.com have sections where skin shade preferences can be selected. There is a greater desirability linked to light brown skin, versus darker brown skin. While Kalinda’s skin color is never mentioned outright, her body is marked in the ways that she is framed in the camera, and juxtaposed against Alicia’s whiteness is a stark contrast.

Kalinda might be the queer stain of darkness on sanctified white womanhood. When seen together, they are often seated at a bar, drinking shots of tequila, and having quiet, deeply moving discussions. In “Nine Hours” (Season 2, Episode 9), the firm must work quickly to get a last minute appeal for a death row inmate, and Kalinda works from Alicia’s home. The two are seated on Alicia’s bed, drinking beers. In every scene with Kalinda socializing, alcohol is in her hands. Kalinda has a secretive past, known as Leela Tahiri to some, and does not speak of her childhood. Her upbringing in a middle class neighborhood with doctor émigré parents is a fabrication. We do not know who she is, but what we do know is that she is secretive, with dark skin, dark clothes, a dark personality, and points toward a darkening of the American Dream.

While her labor is useful to her place of employment, secrecy shrouds the specifics of Kalinda’s quotidian life. We are given glimpses into this, but only under certain conditions. Conversations around Kalinda’s sexuality and lifestyle are the hooks that drive her narrative arc. The most onscreen time given to Kalinda is when these discussions are taking place. In season two, episode six, entitled “Poisoned Pill,” Blake Calamar, a fellow investigator, Kalinda’s rival, and potential male love interest, is blatant about looking into Kalinda’s past, and asks about her sexual orientation:

Blake: They just rated Chicago law firms on their diversity and hiring gays and lesbians and transgenders, whatever. Anyway, Lockhart, Gardner & Bond did not do well. Even though I know, for a fact, that we have gay associates who just aren’t acknowledging that they’re gay. Now, in this day and age, why would someone not be upfront about their sexual orientation?

Kalinda: Are you coming out?

Blake: It’s better not to keep secrets…’cause then, people don’t go looking.

In season two, episode 14, “Net Worth,” we see Kalinda with federal investigator, Lana Delaney, who has tried to seduce her sexually, as well as professionally, wanting her to come work for the FBI. In a low lit scene, with both women taking up equal parts of the camera frame, and a discussion about Kalinda’s sexual proclivities:

Lana: Why do you like men?

Kalinda: Why do I like men?

Lana: Yes, sex with men. Why do you like it?

Kalinda: I don’t distinguish.

Lana: You don’t have a preference?

Kalinda: Uh…

Lana: You were saying?

Kalinda: I was saying Italian, Mexican, Thai — why does one choose one food over the other?

Lana: Because sex is not food.

Kalinda: Because of love.

Lana: Or intimacy. Don’t you want intimacy?

Kalinda: No. [glares angrily at Lana.]

Lana: [Phone rings] I have to get that.

Kalinda: Then you’re going to need your foot back.

In an interview with The Daily Beast, Archie Panjabi argues that Kalinda is “never looked at as somebody who’s bisexual or ethnic,”[11] but this does not resonate with the popularity the character has garnered on the show. Kalinda’s skin color and sexual orientation are precisely two markers of her appeal; she is indeed multifaceted, but her lack of transparency and guarded secrecy about her life and sexual preferences are the draw of her narrative arcs. She is troubling to the norm, both men and women desire to get to know her, and bed her.

At the end of season three, Kalinda’s queerness is confirmed. She sits with Alicia at a bar, and Alicia asks her if she is gay. Kalinda replies, “I’m not gay. I’m…flexible.” She has been indicted by a grand jury for illegal activities, and is under heavy surveillance by the FBI, CIA, and IRS, for tax evasion. Though she is an independent, brave woman, she is under the thumb of many regulatory agencies. Her employers, both past and current, think that too many sources leak classified information to her, and freely comment upon her ethics, and question the ways in which she gets her jobs done. She may testify against her employers, turn evidence in, or get indicted and become part of the prison industrial complex. If she testifies, and does rat out sources, she may be killed by the city’s top meth dealer. The feeling conveyed by Kalinda is one of uncertainty, discomfort, and unchecked desire. Actively resisting old narratives of “good South Asianness,” Kalinda’s story continues beyond conventional conclusions, and this is productive, because it suggests a different outcome for her life, outside the realm of the “good Asian woman.” She must face dangers that other citizens may not need to process; those who do not look like the official face of a queer national corpus are subjected to harsher modes of policing. She is not an entirely negative portrayal of Indian women, but some might argue that parts of her construction might shore up colonial ideologies. She may, in fact, be the product of a fantasy-riddled colonial hangover.

[1] Puar, Jasbir and Rai, Amit. “Monster-Terrorist-Fag: The War on Terrorism and the Production of Docile Patriots.” Social Text, 72 (Volume 20, Number 3), pp. 117-148. Duke University Press, Fall 2002

[2] Oishi, Eve. “Bad Asians: New Film and Video by Queer Asian American Artists,” p. 221

[3] Gopinath, Impossible Desires, 23.

[4] Royle, Nicholas. “Supplement: The Sandman.” The Uncanny. New York: Routledge, 2003. p. 42

[5] Freud, “The Uncanny,” Studies in Parapsychology, p. 20

[6] Ibid, 28.

[7] Freud, Sigmund. “The Uncanny” in Studies in Parapsychology, ed. Philip Rieff. New York: Collier Books, 1963. p. 20

[8] Present most notably in works by Bharati Mukherjee, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, Meena Alexander, Ginu Kamani.

[9] As described by Kalinda’s former girlfriend, Donna, in Season Two, Episode 6, “Poisoned Pill.”

[10] http://jezebel.com/5900928/your-vagina-isnt-just-too-big-too-floppy-and-too-hairyits-also-too-brown

[11] Lacob, Jace. “The Good Wife: Archie Panjabi Talks About Playing Kalinda.” The Daily Beast. 14 Feb. 2011. Web. 16 Feb. 2011

Dr. Rosie Kar is a writer, poet, teacher, photographer, and social justice advocate. She teaches courses on popular culture and gender and sexuality, in the Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and the Department of Asian and Asian American Studies at California State University, Long Beach, and in the Department of Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at UC Santa Cruz.