Author: Amber Leab

Here’s the part where we ask for your help.

- Donate via PayPal. Notice the “Donate” tab at the top right of the page. If you’re a reader who supports what we do, consider donating to the cause. Any amount, however small, is a greatly appreciated gesture of support and will help pay for our expenses.

- Purchase items through our Amazon store. We have a widget in our sidebar called “Bitch Flicks’ Picks.” If you go on to make purchases through our site, we earn a small percentage of the proceeds, and if it’s an awesome feminist film, TV show, or book–then we all win.

If you can’t afford a financial contribution, there are a number of things you can do to help.

- Like our Facebook page and share it with your friends

- Follow us on Twitter

- Subscribe to our RSS feed

- Subscribe to posts via email

- Follow us with Google Friend Connect

- Stumble our posts

- Comment

- Contribute a review, analysis, or other related piece (we’re open to original and cross-posts)

- Keep reading!

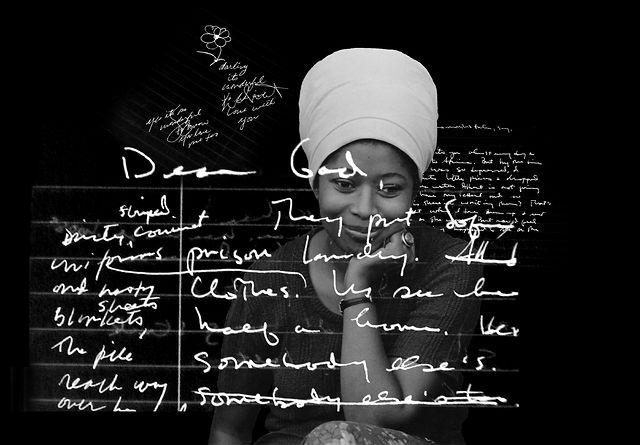

Preview: ‘Alice Walker: Beauty In Truth’

|

| You can help Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth by donating to its Indie GoGo campaign. |

“The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don’t have any.”

–Alice Walker.

ALICE WALKER: BEAUTY IN TRUTH has been 4 years in the making. During this time we have most definitely rolled up our sleeves, put our heads down and dedicated ourselves to getting this film out in the world by any means necessary. On this ever eventful journey, we have been joined by some truly committed and amazing people who share our vision to tell this inspiring story of hope. We have got this far with the help of generous donations from individuals, grants and awards, major extensions on our personal credit cards and most recently filmmaker support from ITVS. We have now completed 85% of the filming and are working towards the completion of a rough cut.The filmmaking team is award-winning filmmaker Pratibha Parmar and producer Shaheen Haq.

[…]

Alice Walker’s dramatic life has been lived in a spirit of resistance and grace. Born in 1944, in a paper-thin shack on a cotton plantation, the eighth child of sharecroppers in rural Georgia, her early life unfolded in the midst of violent racism and poverty in the segregated South. Her poor, black, Southern upbringing and her activism in the civil rights movement in Mississippi in the 1960’s greatly influenced her consciousness and shaped her writing. Being forced to ride at the back of the bus, and watching her parents being brutalised by racist segregation, instilled in her a life long commitment to justice and equality. In 2010, Walker was awarded the LennonOno Peace Award for her humanitarian work by Yoko Ono, another visionary and a risk-taker.

Watch the trailer:

If you can afford to, we encourage you to donate to this important project. If not, please help them by spreading the word about the film.

Horror Week 2011: The Roundup

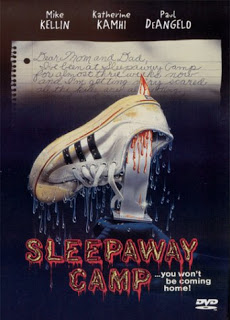

Sleepaway Camp by Carrie Nelson

The shock of Sleepaway Camp’s ending relies on the cissexist assumption that one’s biological sex and gender presentation must always match. A person with a mismatched sex and gender presentation is someone to be distrusted and feared. Though the audience has identified with Peter throughout the movie, we are meant to turn on him and fear him at the end, as he’s not only a murderer – he’s a deceiver as well. But, as Tera points out, the only deception is the one in the minds of cisgender viewers who assume that Peter’s sex and gender must align in a specific, proper way. Were this not the point that the filmmakers wanted to make, they would have revealed the twist slightly earlier in the film, allowing time for the viewer to digest the information and realize that Peter is still a human being.

The Silence of the Lambs by Jeff Vorndam

Starling must unfortunately endure many such difficulties because she works in the male-dominated institution of the FBI. As an attractive woman, Starling receives lascivious looks from nearly every male in the movie. When she and her roommate go jogging in one scene, a group of men jogging the other way turn around to ogle the women’s behinds. Earlier, when Starling is looking for Agent Crawford’s (her boss) office, the men gaze at her as if she were an exotic delicacy. Hannibal Lecter’s psychiatrist Dr. Chilton tries to pick her up initially, “Are you familiar with the Baltimore area? I could show you around.” When she explains she has a job to do, Chilton becomes angry, “Crawford sent you here for your looks–as bait.” Lecter surmises that Crawford fantasizes about Starling and that is why she was selected for the assignment. Even the bespectacled etymologist asks her out. In fact, it is only Lecter who is more interested in getting in her head than her pants.

The Sexiness of Slaughter: The Sexualization of Women in Slasher Films by Cali Loria

The whores in horror are the signature flesh of the slasher flick. Women in this genre have long been given the cold shoulder: cold in as much as they are often lacking for clothing. Often a female character’s dearth of apparel becomes prominent at the pivotal point of slaughter: in cinema, women dress down to be killed. Filmmakers pair scopophilia with the gratuitous gore of killing–leaving viewers to male gaze their way into a media conundrum: When did sexual arousal and brutality towards women pair to become the penultimate money shot?

Amanda Young, Gender Erasure, and Saw’s Unexpected Pro-Woman Attitude by Elizabeth Ray

There are many things that set Amanda apart from most villains in horror movies, the most notable one being that she’s a woman. But more than that, she’s a woman who is not driven by: jealousy, vanity, or obsession over a man. She doesn’t indulge in vampiric, Sapphic tendencies meant to titillate male viewers. And she isn’t sexualized: while reasonably attractive, she isn’t a young, nubile twentysomething, and she dresses in plain, normal clothes, which neither accentuate nor hide her feminine features. And she isn’t demonized either: she’s a not a “bitch” or “whore” who deserves what’s coming to her. Her mundanity is what makes her so appealing: she’s not just an “everygirl,” she’s an everyperson, who, like Jigsaw, is a character that all genders can identify with and sympathize — but her femininity isn’t taken away from her in order to make her stronger or more appealing (she is not given a boyish nickname like “Chris” or “Billy” and doesn’t adopt masculine traits like Ripley did in Alien), which is the most important thing.

Hellraiser by Tatiana Christian

Julia is an interesting character because unlike Kirsty – who experienced a mutual loving relationship between both her father and Steven (her love interest) – Julia had no such thing. Instead, Julia experienced rejection from Frank, her main obsession/love interest and killed off all the men who showed any interest in her (Larry and her victims).

Drag Me To Hell by Stephanie Rogers

I vacillated between these two women throughout the movie, hating one and loving the other. After all, Christine merely made a decision to advance her career, a decision that a man in her position wouldn’t have had to face (because he wouldn’t have been expected to prove his lack of “weakness”). If her male coworker had given the mortgage extension, I doubt it would’ve necessarily been seen as a weak move. And even though Christine made a convincing argument to her boss for why the bank could help the woman (demonstrating her business awareness in the process), her boss still desired to see Christine lay the smack-down on Grandma Ganush. I sympathized with her predicament on one hand, and on the other, I found her extremely unlikable and ultimately “weak” for denying the loan.

The Blair Witch Project by Alex DeBonis

But the film itself denigrates Heather because she accepts responsibility, almost agreeing with the taunts. The most famous scene in The Blair Witch Project is Heather’s tearful confession into the lens. The substance of this confession is that she is responsible for what’s happening to them, but it’s infuriating that Heather takes responsibility and does so at this point. The confession scene tries to make Heather an Ahab-like figure. On the one hand, her tendency to tape allows the narrative conceit of the film to operate. When events take a turn for the eerie and tense, Heather’s obsession with documenting the experience keeps the cameras rolling and allows us to see the ensuing tumult. On the other hand, it puts her energetic striving for a quality film on trial and coaxes from her a confession for a crime she doesn’t actually commit.

The Descent by Robin Hitchcock

While a cave setting evokes female reproductive organs almost inherently, the set design here takes this metaphor to extremes. The women descend into the cave through a slit-shaped gash in the earth, and then must crawl head-first through a narrow passageway into the greater cave system, where the true danger of the monsters await.The monsters, depicted as the products of evolution motivated only by a primal drive for survival, are the perfect elaboration of this cave-as-womb horror metaphor. And as a cherry on top, they rip the guts out of these women.

In their landmark study, “Madwoman in the Attic,” Gilbert and Gubar embraced the figure of Bertha Mason (the insane, ghostlike previous wife of Jane Eyre’s hero, Mr. Rochester, whom he has locked up inside the attic…apparently for her own good and out of the goodness of his heart!) as somewhat of an alternate literary heroine, and started to analyze exactly what was at work in the common themes found in the literature that women were writing during that time period. As women attempted to write themselves into the purely patriarchal forms of literature that they had grown up reading, they faced the limits of the representation of women in heroic roles. So the gothic heroine emerged as somewhat of a compromise: a heroine who is perpetually endangered and perpetually courageous in the face of that danger. This is the precursor of the modern horror movie heroine who, against all logic, insists on checking out that pesky sound in the middle of the night or following the creepy voices outside of her room.

Let This Feminist Vampire In by Natalie Wilson

While the original film was also excellent, it lacked some of the more overt gendered analysis of the U.S. version. Though this may be due to discrepancies in translation (I saw the film both in Swedish with English subtitles and dubbed in English), the bullying theme running throughout the narrative was framed very differently in the Swedish version. In it, the young male protagonist, Oskar, was repeatedly told to “squeal like a pig” by his tormentors. In contrast, the male protagonist in the U.S. version, now named Owen (played by Kodi Smit-McPhee), is attacked by bullies with taunts such as “Hey, little girl” and “Are you a little girl?”

Inevitably the college kids pick up a hitchhiker, which is where the plot starts to get interesting. This hitchhiker, Baby Firefly (played by Zombie’s wife Sheri Moon), seems odd and off in her own world. She messes with the radio and giggles at the college kids. Both Denise and Mary instantly despise her and are obviously threatened by her sexuality, and as expected both Bill and Jerry like her. While this little battle starts to play out, and Baby is loudly drumming on the car’s dashboard, the car gets a flat tire. Of course the sexy female hitchhiker is a local and her brother can help fix the car. It is when Baby insists that the whole gang come over to dinner that this story finally becomes interesting.

A Feminist Reading of The Ring by Sobia

At the center of the mystery are Samara and her mother, Anna, both women whose sanity is questioned by the narrative. At first glance, the movie seems to be Anna’s creation, and it’s her face that we see in the images on the tape. Anna is implied to have been driven to the brink of insanity and eventually to suicide by Samara, who somehow creates images that burn themselves into the minds of those around her. Samara herself is an ambivalent figure that the movie does not seem to be sure about, which leaves her open to interpretation. While I was convinced of her pure evilness initially, subsequent viewings have made her emerge as a less sinister figure, especially given her portrayal in the Japanese version of the story.

Ellen Ripley, A Feminist Film Icon, Battles Horrifying Aliens…And Patriarchy by Megan Kearns

While both Alien and Aliens straddle the sci-fi/horror divide, one of the horror elements apparent in Alien is Carol Clover’s notion of the “final girl.” In numerous horror films (Nightmare on Elm Street, Halloween, The Descent), the resourceful woman remains the sole survivor, the audience intended to identify and sympathize with her. Oftentimes sexual overtones exist with the promiscuous victims and the virginal survivor. While Alien and Aliens display sexual themes (we’ll get to those in a moment), Ripley isn’t sexualized but remains the sole survivor in the first film. She’s also never masculinized as Clover suggests happens to final girls in order to survive.

Rosemary’s Baby: Marriage Can Be Terrifying by Stephanie Brown

Rosemary’s Baby is one scary movie. It’s about a woman’s lot in a hostile world. It is about a terrible marriage to a narcissistic and selfish person. It is about the fear of motherhood and giving birth. It is convincing as a terrifying movie about the supernatural, and as a life lesson about selling your soul to a metaphorical devil. I like horror to convince me that I have learned something about the dark side of human nature…not just play with gore, or supernatural themes, or catastrophic nightmares. It has to name a fear that we really have, or a truth we find hard to believe, and the best horror enlightens us by showing us the darkness that haunts our lives.

Thanks to all our Horror Week 2011 writers! (Previous Theme Weeks include Mad Men Week and Emmy Week 2011.)

Horror Week 2011: A Feminist Reading of The Ring

|

| “Before you die … “ |

Infection in the sentence breeds

We may inhale Despair

At distances of Centuries

–Emily Dickinson

|

| “And it’s, like, somebody’s nightmare.” |

|

| “Anna and Samara.” |

Horror Week 2011: The Blair Witch Project

|

| The Blair Witch Project (1999) |

Viewers might hope that with its unconventional approach, shoestring budget, and status as the first blockbuster powered by Internet buzz, The Blair Witch Project could offer horror fans something they haven’t seen before, specifically in terms of how women are represented. At first, the flick looks promising because it centers on a female lead in a position of authority. While it’s arguable whether The Blair Witch Project’s through-the-viewfinder conceit is actually innovative (cinephiles like to point to the correlations between Blair Witch and Man Bites Dog and Cannibal Holocaust), it’s safe to say that—in 1999, at least—no films with this particular conceit had enjoyed such widespread popularity. The presence of this conceit might account for the film’s success, coming as it did in the watershed era of reality television. Its lo-fi, DYI qualities lend the film a realism that at that time felt new and potentially persuasive. While the ensuing years have brought us further variations on the motif—Cloverfield, Paranormal Activity, and Super 8, among others—it’s also become much easier to see how The Blair Witch Project, for all its putative realism, renders unduly harsh judgments on its female lead.

Horror Week 2011: Drag Me to Hell

This review, written by Stephanie Rogers, was originally published in June 2009.

But, I ask you, can a film that sacrifices a goat and a kitten really be taking itself so seriously?

Everything that exists in this movie is a stereotype: the skinny blonde who used to be fat and now refuses to eat carbs, the skinny blonde’s self-hatred and rejection of her farm-girl roots, the rich boyfriend who will undoubtedly help her escape it all, his rich and consequently vapid, overbearing parents who want their son to marry a nice upper-class girl, the patriarchal workplace where the skinny blonde gets sent for sandwiches by her male coworkers, the jerk who sells out a coworker in order to get promoted, the brown-skinned psychics who hold hands around a table and chant in an attempt to invoke The Evil Spirit, the gypsy, obviously, and not least importantly, the fucking goat sacrifice.

Everything that exists in this movie is a stereotype: the skinny blonde who used to be fat and now refuses to eat carbs, the skinny blonde’s self-hatred and rejection of her farm-girl roots, the rich boyfriend who will undoubtedly help her escape it all, his rich and consequently vapid, overbearing parents who want their son to marry a nice upper-class girl, the patriarchal workplace where the skinny blonde gets sent for sandwiches by her male coworkers, the jerk who sells out a coworker in order to get promoted, the brown-skinned psychics who hold hands around a table and chant in an attempt to invoke The Evil Spirit, the gypsy, obviously, and not least importantly, the fucking goat sacrifice.

The point is: it’s hard to play the I-hated-this-movie-because-of-the-blah-blah-“insert offensive stereotype”-game, when the film unapologetically turns everyone into a caricature.

Drag Me To Hell is about a young woman, Christine (played by Alison Lohman), who makes a questionable decision in an effort to get promoted at the bank where she works. She refuses to give a third extension on a woman’s mortgage loan, and in doing so, the woman, Mrs. Sylvia Ganush (played by Lorna Raver), could potentially lose her home. The twist? Christine could’ve given her the extension. But she chose not to. Instead, Christine wanted to prove to her boss that she’s a tough, hard-nosed, business savvy go-getter, and therefore certainly more qualified than her ass-kissing male coworker (who she’s in the process of, ahem, training) to take over the assistant manager position.

Then, as luck would have it, all hell breaks loose.

For the next hour and a half, these women go all testosterone and maniacally kick each other’s asses. This isn’t an Obsessed-type ass-kicking, where Beyonce Knowles beats the crap out of Ali Larter over, gasp, a man! and where all that girl-on-girl action plays like late-night Cinemax porn for all the men in the house. (Read Sady Doyle’s excellent review of it here). No, this is strictly about two women, one old, gross, and dead, the other young, gorgeous, and alive, trying to settle a score. Christine wants to live, dammit! And Mrs. Ganush wants to teach Christine a lesson for betraying her in favor of corporate success!

For the next hour and a half, these women go all testosterone and maniacally kick each other’s asses. This isn’t an Obsessed-type ass-kicking, where Beyonce Knowles beats the crap out of Ali Larter over, gasp, a man! and where all that girl-on-girl action plays like late-night Cinemax porn for all the men in the house. (Read Sady Doyle’s excellent review of it here). No, this is strictly about two women, one old, gross, and dead, the other young, gorgeous, and alive, trying to settle a score. Christine wants to live, dammit! And Mrs. Ganush wants to teach Christine a lesson for betraying her in favor of corporate success!

I vacillated between these two women throughout the movie, hating one and loving the other. After all, Christine merely made a decision to advance her career, a decision that a man in her position wouldn’t have had to face (because he wouldn’t have been expected to prove his lack of “weakness”). If her male coworker had given the mortgage extension, I doubt it would’ve necessarily been seen as a weak move. And even though Christine made a convincing argument to her boss for why the bank could help the woman (demonstrating her business awareness in the process), her boss still desired to see Christine lay the smack-down on Grandma Ganush. I sympathized with her predicament on one hand, and on the other, I found her extremely unlikable and ultimately “weak” for denying the loan. (Check out the review at Feministing for another take on this.)

Mrs. Ganush, though, isn’t your usual villain. She’s a poor grandmother, who fears losing her home. She literally gets down on her knees and begs Christine for the extension. Sure, she hacks snot into a hankie and gratuitously removes her teeth here and there, but hey, she’s a grandma, what’s not to love? Other than, you know, evil.

I love that this movie is about two women who are both arguably unlikeable to the point where you hope they either both win or both die. (The last time I remember feeling that way while watching a movie was probably during some male-driven cop/gangster drama. Donnie Brasco? American Gangster? Goodfellas? Do women even exist in those movies?) Everyone else is a sidekick, including the doe-eyed boyfriend (played by Justin Long), who basically plays the stand-by-your-(wo)man character usually reserved for women in every other movie ever made in the history of movies, give or take, like, three.

I love that this movie is about two women who are both arguably unlikeable to the point where you hope they either both win or both die. (The last time I remember feeling that way while watching a movie was probably during some male-driven cop/gangster drama. Donnie Brasco? American Gangster? Goodfellas? Do women even exist in those movies?) Everyone else is a sidekick, including the doe-eyed boyfriend (played by Justin Long), who basically plays the stand-by-your-(wo)man character usually reserved for women in every other movie ever made in the history of movies, give or take, like, three.

But at the same time, one could certainly argue that Christine’s unwillingness to help Mrs. Ganush, which results in Christine spending the next three days of her life desperately trying not to be dragged to hell, plays as a lesson to women: you can’t get ahead, regardless, so just stop trying. (Dana Stevens provides an analysis on Slate regarding this double-edged-sword dilemma that Christina finds herself in.)

Some have also argued that Drag Me To Hell exists in the same vein as the Saw films: it’s nothing but torture porn and obviously antifeminist. Yes, it’s gory, with lots of nasty stuff going in and out of mouths (Freud?), but the villain gets her share, and Christine hardly compares to the traditional heroine of lesser gore-fests: for one, she’s strong, much stronger than the horror-girls who can’t seem to walk without falling down in their miniskirts, and for the most part, she makes life-or-death decisions on her own, growing stronger and more adept as she faces the consequences of those decisions.

Some have also argued that Drag Me To Hell exists in the same vein as the Saw films: it’s nothing but torture porn and obviously antifeminist. Yes, it’s gory, with lots of nasty stuff going in and out of mouths (Freud?), but the villain gets her share, and Christine hardly compares to the traditional heroine of lesser gore-fests: for one, she’s strong, much stronger than the horror-girls who can’t seem to walk without falling down in their miniskirts, and for the most part, she makes life-or-death decisions on her own, growing stronger and more adept as she faces the consequences of those decisions.

Perhaps most importantly, Christine isn’t captured by some sociopathic male serial killer and helplessly tortured in a middle-of-nowhere shed for five days. She trades blows with her attacker, and at one point, in pursuit of Mrs. Ganush, she even states that she’s about to go, “Get some.” (Ha.)

I personally read the film as an attempt to uphold the qualities our society traditionally categorizes as “feminine” characteristics: compassion, understanding, consideration, etc. I’m not suggesting that men don’t also exhibit these qualities, but when they do, they’re often considered weak and unmanly, especially when portrayed on-screen, which is demonstrated quite effectively when Christine confronts her male coworker about his attempts to sabotage her career; he bursts into tears in a deliberately pathetic played-for-laughs diner scene.

But it’s only when Christine rejects these qualities in herself (the sympathetic emotions she initially feels toward Mrs. Ganush), and consciously coaxes herself into adopting hard-nosed, traditionally “masculine” characteristics (which her male boss rewards her for), that she’s ultimately punished—and by another woman, no less. The question remains, though, is she punished for being a domineering corporate bitch, or is she punished for rejecting her initial response to help out? Regardless of the answer, the film makes a direct commentary on the can’t-win plight of women in the workplace, and, newsflash: it still ain’t pretty.

Watch the trailer here.

Horror Week 2011: Hellraiser

|

| Hellraiser (1987) |

When people talk about classic horror movies, they’re almost always referring to the eighties which contained Nightmare on Elm Street, The Thing, and Child’s Play to name a few. Hellraiser, released in 1987, is no exception. While the movie lacks a lot of the high-tech special effects we’ve grown used to in contemporary cinema, the make-up in Hellraiser is impressively chilling. Although I’d seen the film several times prior (including all its sequels), I still found myself cringing and gagging as Frank emerged from the floorboards as little more than a slimy substance with bones.

“What’s the matter? It’s what you brought me here for, isn’t it?”

“I suppose so, yes.”

“So what’s your problem? Let’s get on with it.” And as Julia’s reluctance seems to grow, he growls, “You aren’t going to change your fucking mind, are ya?”

Tatiana Christian is a blogger at Parisian Feline, who writes about sexuality, gender and basically her thoughts on social justice and life. She previously contributed a review of Slumdog Millionaire to Bitch Flicks.

Horror Week 2011: The Sexiness of Slaughter: The Sexualization of Women in Slasher Films

Over the course of the series’ eight one-hour episodes, those skilled and sexy enough to command the screen survive. Those who don’t will “get the axe” until only one strong, seductive and stellar actress remains, earning the break-out role in “Saw VI” and the title of Scream Queen.

The season 1 winner, Tanedra Howard, won the chance to show audiences just how seductive and stellar she could look while being tortured.

As years passed, young audiences required that gruesome images become more intense and explicit for them to become scared…In 1978, a movie called Halloween not only sold more tickets than any other horror film, it broke all previous box-office records for any type of film made by an independent production company. Hollywood immediately tried to tap into the success of Halloween. Films such as Friday the 13th, Don’t Go In the House, Prom Night, Terror Train, He Knows You’re Alone, and Don’t Answer the Phone were all released in 1980. These movies, which are some of the first slasher films, were extremely successful. However, with their increasing popularity came strong criticism. Slasher films were condemned for frequently portraying vicious attacks against mostly females and for mixing sex scenes with violent acts.

This popular kill from Jason X involves scientist Andrea getting her face dunked in liquid nitrogen. While struggling with Jason, Andrea’s shit (half of what could be a sexy scientist Halloween costume) rides up revealing to the audience the bottom of her full breasts. While this small glimpse does not equate itself to the arousal of an all-out sex scene, it is intentional. From costuming to blocking, every aspect of the character’s femininity in this scene was meticulously plotted. The fact that filmmakers, audiences, and Maxim find a kill scene more enticing if the woman is sexy and almost shirtless speaks to the fact that modern horror films sexualize slaughter.

Social scientists have expressed concern over the negative effects that slasher films may have on audiences. In particular, exposure to scenes that mix sex and violence is believed to dull males’ emotional reactions to filmed violence, and males are less disturbed by images of extreme violence aimed at women (Linz, Donnerstein & Adams, 1989). These effects on male viewers are said to derive from “classical conditioning”.

Sapolsky and Molitor rebuff this idea, believing that the pairing of sex and violence does not occur often enough for classical condition to occur. However, they further state:

The concern over potential negative effects of exposure to slasher films remains. Possibly, depictions of violence directed at women as well as the substantial amount of screen time in which women are shown in terror may reduce male viewers’ anxiety. Lowered anxiety reduces males’ responses to subsequently-viewed violence, including violence directed at women. Accordingly, the desensitizing effects of slasher films may result from a form of “extinction” and not from classical conditioning.”

It appears that no matter how you slice it, this pairing, on unconscious level, does not leave viewers unaffected.

Horror Week 2011: The Silence of the Lambs

|

| The Silence of the Lambs (1991) |

Horror Week 2011: Sleepaway Camp

|

| Sleepaway Camp (1983) |

But Angela’s not deceiving everybody because she’s a trans* person. She’s deceiving everybody because she’s a (fictional) trans* person created by cissexual filmmakers. As Drakyn points out, the trans* person who’s “fooling” us on purpose is a myth we cissexuals invented. Why? Because we are so focused on our own narrow experience of gender that we can’t imagine anything outside it. We take it for granted that everyone’s gender matches the sex they were born with. With this assumption in place, the only logical reason to change one’s gender is to lie to somebody.