Somewhere between Marty McFly and Jessica Rabbit, it became quite clear that one thing Robert Zemeckis’ characters have in common is an utter defiance of the laws of nature. Now, channeling this notion in Isabella Rossellini’s role of Lisle von Rhoman, emerges the ultimate temptress: “Sempre viva – live forever.”

However, for the women of this movie, it isn’t so much the promise of eternal life that entices them to drink the rejuvenating potion offered by Lisle. It is the ever-lasting youthful appearance they are after. For this they are willing to spend all the money they have, which seems to them like a small price to pay. But “the sordid topic of coin,” as Lisle calls it, is not the only price eternal youth comes at; set against the backdrop of a seemingly never-ending thunderstorm, Zemeckis unfolds a lurid tale of (attempted) murder, jealousy and spray paint.

It all begins with the aging starlet Madeline Ashton (Meryl Streep) performing an ill-conceived version of Tennessee Williams’ “Sweet Bird of Youth,” and people stepping on her photograph as they leave the theater mid-show. It is no secret that working as an actress and living as a human being subject to the process of aging don’t go well together – the limitations of which real life Meryl Streep has been known to point out.

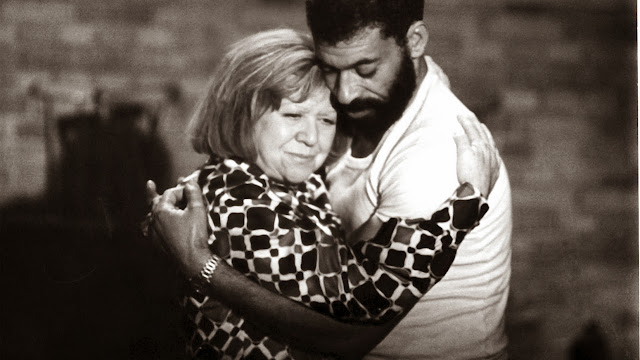

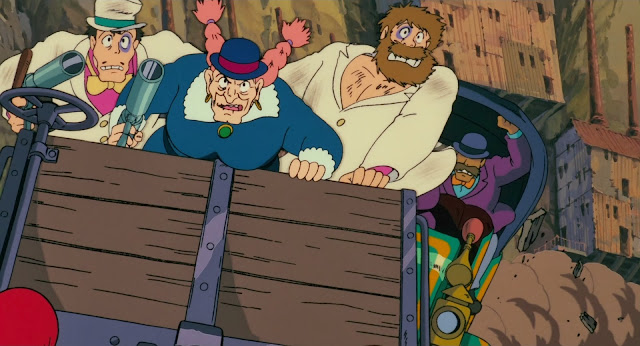

|

| Helen Sharp (Goldie Hawn) after Ernest leaves her |

As the aspiring writer Helen Sharp (Goldie Hawn) introduces her fiancé Ernest (Bruce Willis) to her long-time frienemy Madeline, their lives start to unravel. Instantly smitten, Ernest loses no time to break off the engagement and marry Madeline instead. His occupation as a plastic surgeon should prove to be beneficial to Madeline’s crumbling career.

“Tell me, doctor, do you think that I’m starting to need you?” she asks him, flirtingly. Her choice of words illustrates the undisputed consensus that, at a certain age, women need to act on the fact that time is taking a toll on their appearance. Retaining a youthful image has become a need like breathing or eating (in moderation, by all means).

Meanwhile, Helen’s appearance undergoes three stages. Starting off as rather mousy and plain, she gains weight after being left by Ernest, resulting in the clichéd cat lady couch potato. The camera mocks her voluminous buttocks on more than one occasion. Due to her inertia as well as an obsession with her rival Madeline, she is admitted to a mental hospital where a doctor yells at her for being overweight. Disregarding the fat-shaming, she plots her revenge. In a cut to seven years later, we see her as what society describes as a desirable beauty, finally having managed to get her life back together. It seems that success and appearance go hand in hand. Her book (titled “Forever Young”) finally sells, as she looks fresher than ever – all thanks to a little magic potion, which Madeline is about to happen upon herself shortly.

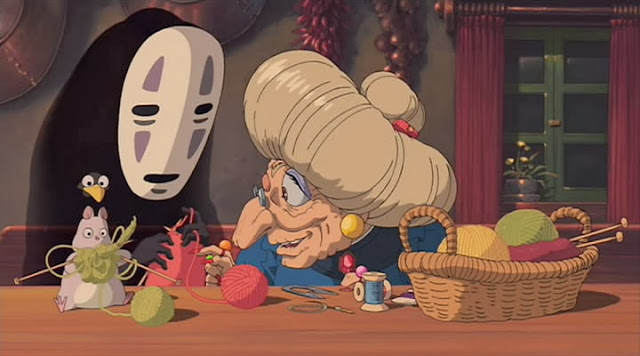

|

| Ernest (Bruce Willis) and Helen |

Ageism You Can Drink

Madeline Ashton is a regular at a spa where she routinely receives extensive (as well as expensive) facial treatments. It is run by people with European accents, which, in combination with Isabella Rossellini’s character, allows for the impression that the beauty and youth lobby is run by a wealthy Eurotrash elite.

Madeline is told that she cannot undergo a treatment, as her last appointment was only a few weeks ago. Frantic in the face of an employee with “22-year-old skin and tits like rocks,” she begs for a spa treatment, illustrating the obsession with physical appearance women are pressured with.

Upon being offered makeup, she screams, “Makeup is pointless! It does nothing anymore!” thus highlighting a problem many women, especially actresses, face. Once hiding behind a lot of makeup no longer serves the purpose of rejuvenation, more drastic measures have to be taken. In addition, Madeline’s frenzy demonstrates the idea that Botox and collagen treatments as well as plastic surgery often have addictive potential.

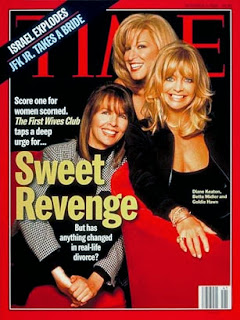

|

| Madeline (Meryl Streep), Helen, and Ernest |

A staff member apologizes, explaining that they are “restricted by the laws of nature.”

Cue Lisle von Rhoman.

“Screw the laws of nature!” she shouts furiously at one point. Defying every physical law, she is just what Madeline is looking for. Between her twenty-something boyfriend cheating on her with someone his own age, and her husband Ernest having a newfound interest in the now youthful Helen Sharp, Madeline has a nervous breakdown. Youth seems to be all that matters to society, and she has internalized the desire to keep up.

Lisle describes aging as “life’s ultimate cruelty – it offers us the taste of youth and vitality and then makes us witness our own decay.”

Her remedy: “a touch of magic in this world obsessed with science.”

|

| Madeline and Helen |

While Meryl Streep was appalled to be offered as many as three different roles as witches as she turned 40, her character in Death Becomes Her now resorts to supernatural powers as an alternative to medical treatments in order to battle aging – when really she should be battling ageism instead.

The women of this movie are consistent with the idea that they are only worthy of success, men, or happiness as long as they are – or appear to be – young. As Madeline watches her body age in reverse after consuming the potion, she exclaims cheerfully, “I’m a girl!”

Hence, womanhood is based on certain physical features defined by society to please the eye. This is mirrored in the character of Ernest who desires whoever looks the youngest, yet accuses Madeline of being cheap for wanting to maintain a youthful facade.

While Ernest is portrayed as a “pushover,” whose domineering spouse makes his life a living hell, we watch his spirit break and his life force dwindle as he is increasingly emaciated and, most notably, emasculated. He is undoubtedly condemned and punished for this until, ultimately, he stands up to Madeline and Helen, which enables him to regain his dignity and lead a decent life after all. Women’s dominance is clearly demonized in Death Becomes Her. It entails depraved moral values, hysteria, and, naturally, a good old cat fight. Helen and Madeline engage in a bizarre brawl that results in a grotesquely comic CGI spectacle. As he lets them lash out at each other, Zemeckis does things to the human body previously only seen in cartoons. The chronic bitchfight based on envy, that the two of them have been carrying out for years in much more subtle ways, has now extended to the physical dimension.

|

| Helen, after Madeline shoots her |

Life As We Know It

“It’s alive!” Helen calls out in a nod to Mary Shelley as she sees Madeline’s zombified self happily walking around the house. In a previous foreshadowing analogy, Ernest asks their housekeeper about Madeline, “Is it awake?”, emphasizing his despise for his oppressive wife on the one hand and the objectification of the woman monster on the other.

After shooting a hole through Helen’s stomach, Madeline cheers, “These are the moments that make life worth living.”

And yet, alive is a thing both women are not even close to being. The forces of nature have been tampered with, and disaster is taking its course. Death Becomes Her sends a pretty clear message when it comes to the distribution of power, morality and, ultimately, gender roles. Life, as many a patriarch has come to know and appreciate it, has been turned upside down. Here, a reversal of gender roles results in the collapse of the main characters’ lives.

The moral decay is mirrored in the disintegration of Helen’s and Madeline’s faces. This is where they realize their dependency on Ernest, who has been fixing their lesions with spray paint. Even beyond death, beyond eternal beauty, they still need the plastic surgeon to fix their crumbling visages. “What if it fades? What if it chips? What if it rains? Will he come back for touch-ups?”

As it turns out, he won’t, and they will have to master the skill of restoring their faces themselves.

|

| Madeline’s turning point |

This is the turning point of the movie. All the conflicts revolving around jealousy, beauty, and, of course, youth, are henceforth turned into a spirit of sisterhood. The dependence on Ernest transforms into a friendly co-dependent relationship between the two women. However much of a love-hate sentiment resonates throughout the final part of the movie, friendship and solidarity triumph. The special bond that Madeline and Helen share is still based on the wish for eternal youth, but they have finally turned to each other.

Meanwhile, Earnest has been living his life without them, his new motto being “Life begins at 50.” As a man, he can afford this attitude. Earlier on, as Madeline and Helen attempt to convince him to drink the potion and attain immortality, the thought of a youthful appearance never even crosses his mind.

Instead, he contemplates being able to continue his career. Eternal youth is not the determining factor for him. In the light of an everlasting life, in contrast, Ernest refuses to drink it. This goes to show that men, as opposed to women, do not face the terror of the beauty industry in quite the same way.

|

| Helen and Madeline still prevail |

In fact, he is rewarded for this decision later on by the pastor at his funeral who asserts that Ernest, just by being a remarkable man who has gone on to found disputable institutions like “The Menville Center for the Study of Women,” he has achieved eternal life. Even after his death he has accomplished eternal youth, as he “lives on in his children.” The irony of this causes Helen and Madeline to get up and leave, not without declaring, “Blaaa blaaa blaaa.”

And yet, as tragic an ending as they face, Madeline and Helen prevail, long after Ernest’s death. Thirty-seven years of interdependent touch-ups later, they now look like bizarre zombie puppets. As they drag their brittle bodies away from the funeral, they fall down a flight of stairs and break into smithereens.

With all their separate body parts scattered across the ground, they are still best friends. This is the actual happy ending – one of solidarity, friendship and emancipation.

Artemis Linhart is a freelance writer and film curator with a weakness for escapism.