Watch Tech Support:

Author: Bitch Flicks

LGBTQI Week: Bully

|

| Bully (2011) |

This piece by Monthly Guest Contributor Carrie Nelson previously appeared at Bitch Flicks on May 7, 2012.

|

| Kelby in Bully |

|

| Ja’Meya in Bully |

LGBTQI Week: I Need a Hero: Gus Van Sant’s ‘Milk’

|

| Movie poster for Milk |

This guest review by Drew Patrick Shannon previously appeared at Bitch Flicks on September 21, 2011.

LGBTQI Week: Transamerica

“No third person,” says the cis therapist paternally, jumping to her role, which is of course to moderate the way that the trans woman experiences her gendered self.

“My son,” the trans woman agrees, because she is a good trans woman, one which the audience is supposed to respect and admire, except wait–isn’t that Felicity Huffman, who is totally not a trans woman at all? Psyche! You’re watching Transamerica, and director Duncan “wow, trans women really don’t look like Daniel Day Lewis in a dress?!?” Tucker is about to teach all you trans women in the audience how you need to behave in order to become a real woman!

Cissexist ideas are built into the structure of Transamerica. I’ve criticized the trope of the “journey” before in cis narratives of trans lives–cis people love to tell us about our trans “journey.” They love asking how it’s going, telling us how much they support us in it, that whole party line. Now, this movie is literally about a woman going on a cross country road trip so that she can get bottom surgery–and thus, within the film’s cissexist logic, become a “real woman.” She has to do this because she’s got a kid from an affair back when she was still presenting as male, and in order to satisfy her therapist that she’s ready to get surgery, she needs to deposit this kid on the West Coast.

You don’t really have to watch this movie to know it’s going to be a real winner. Just read an interview with the director, then imagine what kind of movie a guy like this would make about a trans woman. He pulls out gems like, “I did a lot of research on transgender women, and most of them don’t look like guys in dresses.” Better yet, that quote is a response to a common query: why on earth cast Felicity Huffman? After all, Calpernia Addams appears in a brief scene, along with a couple of other transgender actresses. Why not cast Calpernia? It’s a mystery. Tucker puts forth that he did his “due diligence” upon discovering that there were “a couple transgender actresses in Hollywood”–what a shock. He also insists that the “couple of transgender actresses” he found “were closeted.” Considering that out transgender actress Calpernia Addams is clearly out, transgender, and in fact in his movie, the mind of Duncan Tucker is simply not to be understood. I will not try. Instead, let’s talk about the real reason Felicity Huffman plays this role.

Tucker says he was looking for “someone who could do stealth–not someone who was going to look like a guy in a dress. . .someone you look at and say, ‘She could be a woman.'” In the context of his casting choice, this quote becomes a kind of post-structuralist gender theory slapstick. Tucker cast a woman, because he was looking for someone who looked like they could be a woman? De Beauvoir called. She wants her famous quotation back. He cast a cis woman specifically, because clearly in this logic, trans women don’t look like they could be women. Or they’re in such deep stealth that they would never want to play a trans woman. The fact that both of these possibilities are disproved by the presence of Calpernia Addams in the film again seems to bother Tucker not at all–after all, he needn’t pay attention to the trans bodies already in the world when he has trans bodies of his own to construct.

Huffman was cast so that Tucker could make her into the transsexual he wanted. He needed a woman, because he is telling a heartwarming story about how Bree–the trans character–turns out to be really a woman after all. Paradoxically, Tucker needs a cis woman, because cis women are the only valid women, to play a trans woman in a movie in which trans women are proved to be valid women. In a story where we’re accepted, our bodies can’t be seen. Only a false version of a transsexual can be accepted, a parody. Tucker’s poisonous brand of “acceptance” cancels our bodies out.

Before Huffman can look plausibly trans, she has to be uglified, and that uglification interests me. The trouble with casting an actual trans person is that we don’t necessarily look like what Tucker has decided he needs a transsexual to look like, but a cis person–Tucker can make her look as hideous as he likes, all in the name of realism! When Transamerica came out in 2005, you may remember how much of the press revolved around the character’s ugliness. Felicity Huffman laughed about how deprecating it was to have to wear all that ugly makeup in interview after interview. In character, she’s caked with goop designed to make her look “trans,” a word which here means, “a little bit manly and a lot aesthetically unpleasant.” In the best example of the film’s “Come See Our Movie About a Hideous Transsexual” school of publicity, the US DVD cover is holographic: tilt it one way, and you have Huffman looking red carpet ready, but tilt it the other and you have her as she appears in the film, frumpy and square-jawed. (Memo for your edification: trans women are frumpy. Duncan Tucker told me.)

|

| DVD cover for Transamerica |

This gimmick mystifies me–what’s it trying to say? That at the beginning of the movie Bree looks one way, but at the end she transforms from an ugly duckling into a beautiful swan? Because she doesn’t. At the film’s end, she looks more or less the same, which in itself contradicts the rest of the film’s logic. According to the cis concept of how surgery works, one is not a real woman before and is a real woman afterward. Transamerica supports this narrative in which a trans woman goes under the knife and comes out a different person–Bree’s whole raison d’être is obtaining surgery, and at one point she actually says, and I quote, “Jesus made me this way so I could suffer and be reborn the way he wanted me.”

Sure, at that point she’s pretending to be a missionary, which she really isn’t–this movie’s plot is just as much a gem of shit as the rest of it–but Huffman acts so goddamn much in the scene that we’re clearly supposed to assign a measure of emotional reality to the moment. But after her surgery, there Bree is, looking the same, and not reborn at all, because the film also has to fulfill the cissexist belief that trans people are irretrievably trans, irretrievably ugly, even if we don’t look like Daniel Day Lewis in a dress. The Daniel Day Lewis in a dress comparison, by the way, is an actual Tucker original.

There’s only one major difference between Bree pre-surgery and Bree post-surgery, actually: now she’s fit for the public cis eye. We see Bree at work at the beginning of the film in back of a restaurant washing dishes, and by the end, she’s moved up to waitressing. She even talks to some people! Which is a relief, because it’s established early on that Bree’s only connection with humankind is that horrible cis therapist I mentioned before. Where are that woman’s ethics, anyway? When did it become proper practice to require a trans woman to take her son on a road trip before you write her a surgery letter? I don’t know; I wish I could say I found this part of the movie implausible, but cis people, you never know. The point is that before her surgery, Bree is too hideous to go out in public and make connections, but at least bottom surgery changes that. THANK GOD.

As trans women invariably are when they aren’t fetishized, Bree is desexualized. In the whole film, we see her flirt once, schoolgirlishly–which is fitting with the style of dress the filmmaker has given her. Said style entails a wardrobe like a sixteen-year-old Mennonite who has just left the church and discovered the color lavender, and is milking her newfound glory for all it’s worth. I have never seen a trans woman who dresses like this. I have never seen a cis woman who dresses like this. According to an interview with Huffman, it’s because Bree orders her clothes from catalogues rather than buying them in shops, because as we all know trans women are unable to buy clothes in public? I’m joking–obviously this is an issue trans women face, but I have yet to meet one who dealt with it by dressing like a cross between a nun and the original 1950s Barbies. By the way, it’s heavily implied that she’ll be able to go back to the man she flirts with after surgery and have a Real Relationship at last. This is because if trans people attempt to have a romantic relationship without getting bottom surgery, we combust.

You know Julia Serano’s seminal trans feminist text, Whipping Girl? You know those machines from cartoons where they’d put the good guy in and the evil version of him would come out? Transamerica is what you get when you put Whipping Girl into one of those machines. In her book, Serano talks about the scenes in media featuring trans women where the trans women put on makeup, clothes, breast forms, and how those scenes exist to remind cis people that trans women are not “real.” Well, Transamerica fulfills its Trans Woman Putting on Lipstick Quota within the first twenty minutes, so you know this is a quality production.

Seriously, this is one of the most misogynistic films I have ever seen: over and over, we see Bree reduced to her body. And what can be more misogynistic than a woman reduced to her body? At one point we even see how damn irrational that womanly estrogen is making her! It’s spotlit in the dialogue, so you can be sure. I’m not sure if all the readers here have encountered the word transmisogyny before, but it is vital vocabulary, and it’s exactly what this movie is riddled with. Transmisogyny is misogyny that’s directed towards trans women, specifically predicated upon their trans status. Trans women experience garden variety misogyny as well, but transmisogyny is specific. When we decide that a woman has to have a certain type of genitalia in order to be acceptable for public view and human relationships, that’s transmisogyny. When we decide that trans women have to enact 50s Mennonite Barbie gender roles in order to look like women, that’s transmisogyny. When we support transmisogyny, we support misogyny; transphobia is a tool of patriarchy. Gee, it sure is nice up here on this soapbox–I’ll just recommend some blogs that get this on the nose and carry on talking about the movie.

At some point in the movie, there is a plot. It seems to involve a mother/son relationship. Kevin Zegers does a good job as the gigolo son, presumably by spending the entire shoot pretending that he’s playing a disaffected hustler in My Own Private Idaho and not this disaster. Kevin Zegers is also SUPER hot, and his beauty combined with his performance makes him the best part of the movie except for Dolly Parton’s theme tune, “Travellin’ Thru,” which is a song by Dolly Parton and thus flawless by nature.

I do not recommend this film. If you feel you must consume it in some capacity, may I suggest distilling the essential elements of the experience? Call up the most transmisogynistic person you know and have them talk to you about what they think bottom surgery signifies. While they talk, look at pictures of Kevin Zegers looking wounded and hot, and listen to “Travellin’ Thru” in one headphone. All of the Transamerica with none of the hassle!

———-

Stephen Ira is a trans femme-inist poet and activist. He has poems forthcoming in EOAGH and Specter Magazine and short fiction forthcoming in The Collection from Topside Press. He blogs about politics at Super Mattachine on WordPress.

LGBTQI Week: Trans Girls and ‘Gun Hill Road’: Marking International Women’s Day For All Girls

As a queer teacher of color, I personally feel a responsibility to bring a range of narratives about the LGBT experience, especially those that have an intersectional lens of race, class, gender, ethnicity, and sexuality, to my students, who themselves acknowledge that the queer images they see in the media are too often of white, upper middle class Will & Grace types. For me, screening a film about a young Puerto Rican trans girl is imperative for teaching students that we need to disrupt mainstream narratives of what it means to be queer, young, and of color in today’s transphobic, misogynistic, and racist world.

In addition to illustrating the struggle between Vanessa and her father, the film offers opportunities for educators to have important conversations about gender and sexual identity and bullying in schools. In one locker room scene, Vanessa is taunted by her peers both in Spanish and English, where phrases like “metemelo” (put it in me) and “don’t forget your panties” are hurled. Scenes such as these should give educators the opportunity to discuss important issues such as sexism, misogyny, homophobia, and transphobia.

Indeed, according to GLSEN’s (Gay, Lesbian, Straight Educator’s Network) 2009 climate survey: “90% of transgender students heard derogatory remarks, such as ‘dyke’ or ‘faggot,’ sometimes, often, or frequently in school in the past year.”

Educators should also note scenes related to discussing bathroom accommodations for transgender youth as well as safe sex practices for all queer youth.

As part of the screening, Rashaad Green, the director of the film, also came to speak to my class. When asked what his goal was in portraying the life of a trans girl, Green responded:

It’s not necessarily a coming out story. I think when we meet Vanessa, we meet somebody who is pretty realized in her own journey. She can’t be who she wants to completely to her own family. But she knows who she is.

To see her change out of her clothes, recite her poetry, and completely bare her soul was powerful.

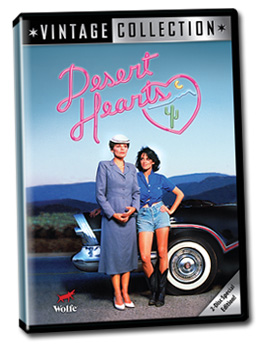

LGBTQI Week: Revisiting ‘Desert Hearts’

|

| DVD cover image of Desert Hearts |

Desert Hearts is one such film for me. In the fall of 1986, still a kid of 22 who had just moved to the city from Podunk, Indiana, I went to the theater in a Boston suburb. There I remember looking around at the audience. I had a hard time believing that I was watching a lesbian romance film in a public place. I don’t think I breathed during the love scene. For the first time in my life, in a mainstream movie theater, I watched a film that gave me a model for what love could be. It made me want to fall in love, to find my own Cay or Vivian and hop on the train to start a life together.

It is a conventional romance, which is one of the reasons that it is so successful. As Jackie Stacey points out, “it uses the iconography of romance films: train stations, sunsets and sunrises, close-up shots, rain-drenched kisses, lakeside confessions, ‘I’ve never felt this way before’ orgasms.” It is those Hollywood conventions that conjure up shared memories of hundreds of heterosexual romances. Thus the filmmaker uses what are sometimes clichés as shortcuts to elicit particular emotions and reactions from the audience. Although the world of 1959 would certainly have been more challenging for these two lovers in the real world, the cinematic world Deitch created signals that there is an all-important happy ending coming up, a romantic Hollywood ending.

Deitch’s use of music also contributes to the romance convention. The country songs of Patsy Cline, Jim Reeves and Johnny Cash are very emotionally evocative. In particular, they conjure up a feeling of wanting that comes from knowing the themes and voices that accompany these artists’ work. The soundtrack, which took up a large portion of the film’s budget, makes brilliant use of the audience’s previous knowledge. We know how we should feel before the scene plays itself out.

|

| Cay and Vivian in Desert Hearts |

Placing the film’s setting in Reno also taps into our shared impressions of the West from movies and popular culture. It is a place in which one can start a new life and throw caution to the wind. The chances for romance certainly would not have felt so hopeful without the wide open spaces and bright, beautiful colors of the Nevada desert. Cay’s cowboy boots and western clothes make her the equivalent of the cowboy who sweeps the newcomer to town off of her feet. It’s the wild westerner who charms the shy school marm, just like we’ve seen a million times in the movies.

Others (like Mandy Merck) discuss Desert Hearts as conventional, criticizing it for not being challenging enough, not tackling issues of lesbian identity, for example. For me, that criticism totally misses the point. Deitch intentionally did not make an issues kind of film. She took Hollywood formula and tilted it on its ear, creating a lesbian love story that audiences still crave today.

———-

Angie Beauchamp is a freelance internet marketer, making her living by managing other people’s blogs and social media. She also runs the Lesbian Film Review.

LGBTQI Week: Frida

This review by Editor and Co-Founder Amber Leab previously appeared at Bitch Flicks on March 30, 2012.

|

| Frida (2002) |

|

| Le due Frida |

Amber Leab is a writer living in Asheville, North Carolina. She holds a Master’s degree in English & Comparative Literature from the University of Cincinnati and a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature & Creative Writing from Miami University. Outside of Bitch Flicks, her work has appeared in The Georgetown Review, on the blogs Shakesville, Opinioness of the World, and I Will Not Diet, and at True Theatre.

LGBTQI Week: The Kids Are All Right

|

| Movie poster for The Kids Are All Right |

“‘That Nic and Jules are a lesbian couple is important to the movie thematically because they are raising a family in an unconventional setting and are more anxious than some parents about how having two moms will affect the mental health of their children. But it could have been the same thing with a divorced couple,’ she says. ‘I always thought we were making a movie about a family, and the threat to the wholeness of the family. It was not about politics. If there was anything calculated, it was how do we make this movie universal — how do we make this a story about a family?'”

“‘Lesbians love it when a married woman has an affair with another woman on film, which is perceived as moving toward authenticity, but we’re not happy seeing a woman in a same-sex marriage have an affair with a man, which to them represents a regression. And raises concerns about whether it adds fuel to the notion that sexual orientation can be changed from gay to straight. Sitting in the audience, I found myself feeling concerned about that as well…'”

“‘It boils down to this: I’m upset because I believe the takeaway from this film will be that lesbians and the families they create need men to be complete.'”

“‘Your mom and I are in hell right now and the bottom line is marriage is hard. It’s really fucking hard. Just two people slogging through the shit, year after year, getting older, changing. It’s a fucking marathon, okay? So, sometimes, you know, you’re together for so long, that you just… You stop seeing the other person. You just see weird projections of your own junk. Instead of talking to each other, you go off the rails and act grubby and make stupid choices, which is what I did. And I feel sick about it because I love you guys, and your mom, and that’s the truth. And sometimes you hurt the ones you love the most, and I don’t know why. You know if I read more Russian novels, then…Anyway…I just wanted to say how sorry I am for what I did. I hope you’ll forgive me eventually…'”

LGBTQI Week: The Good, the Bad, and the Other in Lesbian RomComs

I have a confession: I love bad lesbian romantic comedies. I once had a summer where I watched little else, delighting in the bad hair, worse puns, and silly sex scenes.

Before I begin, I want to offer a point of clarification. When I say that I enjoy “bad” lesbian romantic comedies, I do so because the unfortunate truth is that there is little else (see here). But it is also true that, until we have a bigger pot to choose from, we can’t be too picky.

The bone I’d like to pick here is not regarding bad dialogue or unrealistic sex scenes, but with the depiction of race, religion, and culture in lesbian romcoms to date. And with that, another disclosure: I am not a film critic or scholar. What I am is a queer feminist academic (and self-disclosed lover of bad lesbian film). And what I’ve observed in lesbian romcoms is a noticeable pattern of “othering” when it comes to the acceptance of homosexuality.

There has been a lot of work in feminist and queer theory lately on the concept of “othering,” most prominently with the work on homonationalism, a concept first coined by Jaspir Puar. Without getting too academicy, the concept describes the way in which Western-based understandings of homosexual rights and acceptance are pitted against “other” cultures’ lack of rights/acceptance. It goes without saying that many of these countries themselves (the US is at the top of this list) do not extend full rights to the queer community. However, in positioning themselves against “others,” (white) Western cultures try to promote a more “liberal” and “democractic” showing of acceptance that proves that they are more “advanced” than “other” cultures. I think that this concept has great relevance for the way that lesbian films deal with race, class, religion, and culture.

|

| Movie poster for Chutney Popcorn |

The first example I’ll use to illustrate this phenomenon is the 1999 film Chutney Popcorn, set in New York, and centered around the Indian-American Reena and her white girlfriend Lisa. Although Reena’s sister is married to a white man, which their mother accepts, she “draws the line” at Reena’s lesbianism. Lisa’s mother is completely supportive – in a role almost as annoying in its supportiveness as Reena’s mother’s is in its disproval. The dualistic division of acceptance – white = accepting/brown = disproving – is clear.

In the hopes of gaining her mother’s acceptance, Reena offers to be the surrogate mother for her sister’s child. High jinx ensue. I won’t ruin the ending here (honestly it might be worth watching if you haven’t), but let’s just say that the more traditional characters in the film “evolve” towards the “right” way of thinking by the conclusion.

|

| Shelley Conn as Nina and Laura Fraser as Lisa in Nina’s Heavenly Delights |

Another example of the “othering” phenomenon is found in the 2006 Nina’s Heavenly Delights. While set in Glasgow instead of New York, Nina’s Heavenly Delights also features an Indian/white lesbian couple. Nina, the Scottish-Indian half of the couple, has returned to Glasgow from London, where she ran away to avoid an arranged marriage. She promptly falls for the white Scottish Lisa (apparently the name “Lisa” is code for white lesbian…), under the disapproving eyes of her family. Again, not to give away the ending, but you might guess that there is an “evolving” understanding of sexuality by the film’s end here as well.

The us/them othering and ethnic stereotyping in this film is all the more disappointing as it is directed and co-written by Pratibha Parmar. Parmar is a documentarian primarily known – in feminist circles at least! – for the 1993 film Warrior Marks, produced by and featuring Alice Walker. (If you haven’t seen that one, you should check it out as well – and watch for the cameo by Tracy Chapman, Walker’s partner at the time.)

The films Saving Face (2004) and I Can’t Think Straight (2008; and, yes, that really is the title) also feature disapproval from “traditional” families – Chinese-American in Saving Face, and Jordanian and British-Indian in I Can’t Think Straight. Although the films do not feature white partners with which to contrast the lack of acceptance from their families, cultural stereotypes and the process of othering nevertheless abound in both films.

In offering this critique, I do not want to suggest that cultural, regional, religious, class, and racial nuances in understandings of sexuality do not exist, nor do I think that directors/writers should start to gloss over these elements in their films. What I want to stress is that these nuances are not so black and white (no pun intended). The reality is that, sometimes, white lesbians are shunned from their families of birth, and black lesbians are embraced. And some brown lesbians are not rejected from their religious communities, but quite the opposite. These alternative narratives are not reflected in lesbian film.

It is refreshing then, that the pot of lesbian films to choose from is growing. For example, though technically not a romcom, the recent, and critically-acclaimed, film Pariah is a good example of how racial nuances can be dealt with on screen, showing that lesbians do not live in the “all or nothing” world that previous films suggest. We can only hope that the future of lesbian film will offer more realistic depictions of race, culture, and sexuality.

———-

Gwendolyn Beetham is an independent scholar, the editor of The Academic Feminist, and a semi-professional lesbian film watcher. She lives in Brooklyn. Follow her on twitter: @gwendolynb

LGBTQI Week: Kissing Jessica Stein

|

| Movie poster for Kissing Jessica Stein |

(Warning: Contains spoilers about Kissing Jessica Stein.)

Though words like “bisexual” and “queer” are never used, Kissing Jessica Stein is about sexual fluidity. The Rilke quotation mentioned throughout the film makes this theme obvious:

“It is not inertia alone that is responsible for human relationships repeating themselves from case to case, indescribably monotonous and unrenewed: it is shyness before any sort of new, unforeseeable experience with which one does not think oneself able to cope. But only someone who is ready for everything, who excludes nothing, not even the most enigmatical will live the relation to another as something alive.” (Emphasis added)

Much like Alyssa in Chasing Amy, Helen places a personal ad in the Women-Seeking-Women section because she “excludes nothing” sexually. When it occurs to her that, in all her sexually adventurous years, she has yet to sleep with a woman, she decides to give it a try – hence the personal ad. But she’s completely unprepared for Jessica Stein – who Helen later calls a “Jewish Sandra Dee” – to respond. As the film chronicles the rise and fall of Jessica and Helen’s romantic relationship, it tackles some big questions: Can a woman who’s only dated men have a successful sexual relationship with a woman? When, if ever, is secrecy in a relationship acceptable? Can a relationship with high emotional connection and low sexual compatibility survive?

|

| Jessica and Helen in Kissing Jessica Stein |

Kissing Jessica Stein provides no easy answers to the questions it asks, which I appreciate. The film understands that sexuality is complicated, and not everyone shares the same capacity for fluidity and sexual experimentation. The film also understands that there is no definitive recipe to a successful relationship, because people are different and have radically different priorities when choosing significant others. Jessica and Helen start out coming from similar places – both of them have identified as straight for all of their lives, and both of them want to question that assumption and explore the possibility of dating another woman. In time, they find that they truly are attracted to each other – more than that, they love each other – but that attraction manifests differently in each of them. While Helen has no insecurities about a sexual relationship with Jessica and longs to have the kind of relationship with Jessica that she’s had with men in the past, Jessica is more interested in her emotional connection with Helen than her sexual one. I don’t think this means that Jessica is straight or that she isn’t genuinely attracted to Helen – we never see her in a relationship with a man, so it’s likely that her sex drive is naturally low. Rather than judging Jessica and Helen for their differences, the film shows both women as they are, and it explores the ways in which their differences both cultivate and destroy their relationship.

|

| Jessica and Helen in Kissing Jessica Stein |

When I watch Kissing Jessica Stein now, I’m transported back to a very specific time and place. I remember being sixteen and newly out as bisexual. I remember anxiously anticipating my first kiss from another girl. I remember starting to understand that sexual expression can be flexible and doesn’t have to conform to societal norms. It shouldn’t matter whom we love or what we call ourselves – only that we love at all, and that we express that love in the most honest way we can. Kissing Jessica Stein is not the first film to convey this message, nor does it do it as well as some other films. It’s certainly not as risky as Shortbus, or even Humpday. But it captures a feeling to which many can relate. And even when it fails, it feels far more believable than most comedies of its genre.

LGBTQI Week: Growing Up Queer: ‘Water Lilies’ (2007) and ‘Tomboy’ (2011)

These techniques are uniquely suited to the onscreen portrayal of adolescence. It almost seems churlish to complain that Water Lilies and Tomboy lack full structural coherence, because that’s arguably intentional. Growing up, after all, is not a tightly-plotted three-act hero’s journey with clear turning points, tidy linear progression through the successive stages of personal development, and a satisfying ending. It’s a messy and confusing struggle to find a place in the world, littered with incidents that may or may not ultimately be significant (with no way to tell the difference), and most of the time the morals make no sense.

Sciamma instinctively understands this, and the little stories she tells of growing up queer are given vivid life through her two greatest strengths as a filmmaker: her ability to coax marvelously deep and naturalistic performances out of her young actors, and her eye for a strikingly memorable little scene that perfectly encapsulates a moment of overpowering adolescent emotion – the normally boisterous Anne clutching at a lamppost and weeping in Water Lilies, for example, or Tomboy‘s Laure curling up on the couch, thumb in mouth, suddenly overwhelmed by an earlier humiliation.

Both films are carried on the remarkably expressive faces of their lead actresses. There are no voice-over monologues or expository conversations, but both Water Lilies and Tomboy present the inner life of their protagonists with stunning depth and rawness.

|

| Movie poster for Water Lilies |

Anne, though less conventionally feminine than the other girls, is confidently heterosexual and determined to sleep with the boy she finds attractive. Marie is so eager to spend time with Floriane that she agrees to help her sneak out to meet François, and her yearnings for the lithe bodies slipping through the water are beautifully conveyed through moments such as the shot of Marie shifting, flustered, as Floriane unselfconsciously changes into a swimsuit right in front of her. Floriane herself, despite the reputation she cultivates (perhaps recognizing that denial would be futile – once branded a “slut,” a teenage girl is hopelessly trapped in a no-win morass of contradictory social pressures), eventually confesses to Marie that she has never actually had sex, and in fact is afraid to do so.

“If you don’t want to do it, don’t.”

“I have to.”

“Where did you read that?”

“All over my face, apparently. If he finds out I’m not a real slut, it’s over.”

|

| Movie poster Tomboy |

Any ten-year-old lives in the present, and Mikael meets each challenge as it arises – sneaking away deep into the woods when the other boys casually take a pee break; snipping a girl’s swimsuit into a boy’s, and constructing a Play-Doh packer to fill it; swearing Jeanne to secrecy when Lisa unwittingly tells her about Mikael – even as it becomes increasingly clear to the viewer that eventually Laure’s parents must find out about Mikael. As loving as they are, they still exert some gender-policing of their oldest child: Mom’s delight at hearing that Laure has made a female friend (“You’re always hanging out with the boys”) might have been tempered if she’d remembered that “copine” can also mean girlfriend!

The relationships between the various children are superbly observed, and constitute reason enough to see Tomboy in themselves. The energetic activities of childish horseplay that give Mikael such joy in himself and in his body – dancing enthusiastically with Lisa, playing soccer shirtless, wrestling in swimsuits on the dock – are balanced by the many lovely domestic scenes demonstrating the closeness of Laure’s relationship with Jeanne. This is honestly one of the most moving and genuine cinematic portrayals of a sibling relationship in years, and after her initial shock Jeanne takes to the idea of Mikael like a duck to water, boasting to another child about her awesome big brother, and telling her parents that her favorite of Laure’s new friends is Mikael.

The parents themselves, unfortunately, are much less accepting of Mikael. The film’s ending is ambiguous, allowing for multiple readings of the exact nature of Laure’s queerness; indeed, the film has been criticized as “an appropriation of trans narratives by a cis filmmaker toward her own purposes”; but to me the ending is terribly unhappy. With deep breaths and with profound conflict on Héran’s preternaturally expressive face, the character is forced to claim “Laure,” the name and gender assigned at birth and not the ones of choice. The cissupremacy has won this round.

Though Tomboy is the better film, the two movies make excellent companion pieces. Between them they depict a range of queerness and explore a variety of strategies for growing up queer (and/or female) in a hostile world. And yet they offer no easy solutions, no cheap moralizing, no promise that it gets better. These films, and the characters they portray, simply are. And, in the end, isn’t that the one universal truth of queer people? There is no ur-narrative of queerness. There is no right or wrong way to be queer. We simply are.

Max Thornton is a grad student and a stranger in a strange land, who writes words at Gay Christian Geek and has previously contributed a review of No Country For Old Men.

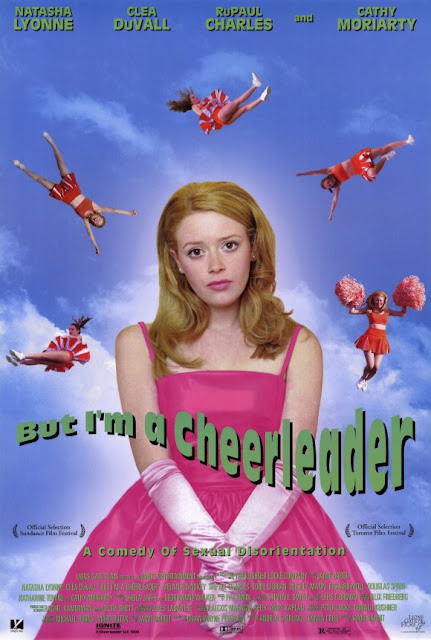

LGBTQI Week: ‘But I’m a Cheerleader’

|

| Movie poster for But I’m a Cheerleader |

It takes an intervention and her parents’ sending her to a “pray away the gay” sort of camp, for Megan to realize she’s gay. Her family sends her to the camp “New Directions” hoping she’ll come back straight, but it only instills in Megan a certainty about her sexuality she hadn’t had before. Not only does she realize that being a lesbian is part of who she is, but through falling in love with another girl at the camp, Megan finds out that she doesn’t want to change it either.

This camp, by the way, looks like it came out of Tim Burton’s nightmares: brightly colored, celebrating conformity and bursting with perkiness.

The director of the camp, Mary Brown (Cathy Moriarty), “cures” homosexuality with a five-step-program. This program mostly involves making the collection of not-so-hetero teenagers act out their gender roles. The different campers are encouraged to find the root cause of their homosexuality – usually being a moment in their childhood where they witnessed adults deviating from gender norms. One’s mom wore pants at her wedding. Another’s mother let him play in pumps. Etcetera.

And so, Mary’s process is to push the adolescents into the cartoon versions of manhood and womanhood. The boys work with Mike (RuPaul) by playing football in solid blue uniforms, fixing a solid blue car and acting out war with solid blue weapons. The girls have their own solid pink version of this: changing baby doll’s diapers, cleaning house and painting nails.

But I’m a Cheerleader does fall into some traps. In portraying characters that are outrageous, there are lots of stereotypically flamboyant gay men. It’s less heinous than most portrayals in the mainstream, and seems to at least be trying to have a purpose. We see Mary’s son, Rock, in short shorts dancing around while ostensibly doing landscape work; living up to the most ridiculous and irritating gay stereotype. But, it’s supposed to be over-the-top to reveal the hypocrisy and absurdity of the camp. Also, while the film does a great job challenging the association of gender and sexuality, and presenting a gender spectrum, it doesn’t explore the spectrum of sexuality so much. Bisexuality is invisible.

But overall, the narrative is one that successfully challenges sexism and heteronormativity. Megan’s journey of falling in love and accepting herself looks normal compared to the antics of those who support the camp. It certainly feels more natural and provides a heart to the film that grounds it.

Megan’s romance with Graham (Clea DuVall) has the perfect combination of silly sweetness and teenage angst. While Graham accepts that she’s gay and is sure it is unchangeable, she is willing to stay in the closet to continue getting support from her family. When Graham and Megan are exposed – Megan leaves the camp, and Graham stays.

Reparative therapy has been the butt of many jokes, but it has existed and been validated by hack psychologists who contort research in an effort to prove that being gay is a mental illness. Robert L. Spitzer who published a study that suggested reparative therapy works, recently made an apology to the gay community because the study has been used to back up harmful methodology. But I’m a Cheerleader tackles an otherwise troubling topic, and makes it funny while still remaining critical.

In the film, while some characters make an effort to be straight, it seems clear that all understand it’s a role they are playing to appease their family. The futile effort could be their chance to remain a member of the community they grew up in. Megan knows that choosing to be open about her sexuality could lead to losing her family, but she chooses pride and oh-so-heroically rescues Graham from the altar of straightness (literally.)

But I’m a Cheerleader isn’t trying to be subtle. The absurdity of gender expectations is put on display with a too-bubbly soundtrack. Because: our society’s gender expectations are insane. And, it’s downright crazy to try to force an identity and sexuality on a person. But, But I’m a Cheerleader gives us a little hope at the end of a wacky lace-trimmed narrative. While the camp wasn’t exposed, while the girls weren’t guaranteed their families, Megan still performed a radical action in embracing both her identity as a lesbian and as a cheerleader. She challenged the expectations of her prescribed role, and still got the girl in the end.

———-

Erin Fenner is a legislative intern and blogger for Trust Women: advocating for the reproductive rights of women in conservative Midwestern states. She also writes for the Trust Women blog and manages their social media networks. She graduated from the University of Idaho with a B.S. in Journalism.