|

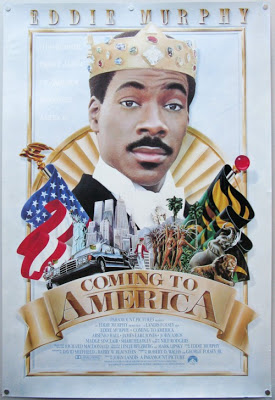

| Coming to America movie poster. |

Written by Leigh Kolb

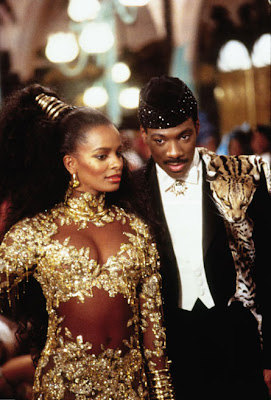

When I was a kid, Coming to America was one of my favorite movies. I’m not quite sure exactly what it was–maybe I just thought Eddie Murphy was really cute–but I’d like to think that I was drawn to its message of valuing female intelligence and independence over subservience.

Coming to America was released in 1988, and helped round out Eddie Murphy’s rise to stardom in the 1980s, from Saturday Night Live to Beverly Hills Cop. While Murphy played side-kicks in many of his early films, Coming to America was unique because it featured Murphy as a romantic lead, and a cast dominated by African Americans.

The premise of the film–a wealthy African prince travels to America to live modestly and find true love, not an arranged marriage–isn’t particularly groundbreaking, but the film worked because it was (and is, sadly) rare to find a black man as a romantic lead, especially in a blockbuster-friendly romantic comedy.

The film begins by taking the audience over the sweeping landscape of the fictional African country of Zamunda, while a South African choir sings. As the camera focuses in on a palace, it’s important to note the stark contrast of this depiction of an African country against the frequent portrayals of Africa in American media, which showcase Africa as a continent in need of our saving (after all, they don’t even have snow at Christmas time).

|

| The royal family of Zamunda: Prince Akeem Joffer, King Jaffe Joffer and Queen Aeoleon. |

Prince Akeem (Murphy) wakes up on the morning of his birthday, and he’s attended to by male and female servants (from royal bathers–beautiful women who clean the “royal penis”–to royal wipers in the bathroom). Akeem doesn’t seem comfortable with any of this, and even requests to use the bathroom alone. At breakfast, his father, King Jaffe Joffer (James Earl Jones), assumes his son must be excited to meet the wife they’ve arranged for him to marry.

Akeem acts unsure, and finally speaks out against being doted upon and the idea that a woman would be chosen for him for his rank, not because she loves him. The tradition of arranged marriage doesn’t sit well with him, and his youthful rebellion takes the form of wanting to fall in love with a woman on his own terms and to be able to be more independent.

Semmi (Arsenio Hall), Akeem’s friend and attendant, serves as a foil to Akeem’s noble goodness. He is baffled that Akeem wants a woman with an opinion instead of having a woman who would follow his every command. Semmi assures Akeem that his wife need only have a “pretty face.”

Akeem asks him, “So you’d share your bed with a beautiful fool?” Semmi says that that’s the tradition for men in power. Akeem says that it’s also tradition for times to change.

While the film isn’t a bastion of female empowerment, feminist nuggets like that pop up throughout the film, which is always refreshing within the confines of the well-worn tropes in romantic comedies.

|

| Akeem asks Imani, his chosen wife-to-be, to speak privately, breaking tradition. |

When Akeem is presented with the beautiful woman who is to be his wife, Imani (Vanessa Bell), he asks to talk to her privately. She proudly tells him, “Ever since I was born, I’ve been trained to serve you.” He pushes to find out more about her, her favorite music, food, anything. But all she says is that she likes what he likes and will obey him. He says, “Anything I say, you’ll do?” after she refuses to not obey him, which is what he wants. He tells her to bark like a dog, and she complies, making a fool of herself as he is convinced this is not the woman he will marry.

The fact that she was “born to serve” this man isn’t an anomaly–in patriarchal cultures steeped in tradition, the idea that women should be indoctrinated to be subservient to men is endemic. (Just last week, a U.S. congressman suggested that young boys and girls have segregated classes to be taught gender norms.)

When Akeem pushes back to his father and tries to get out of the marriage, saying he’s not ready, the king assumes he means sex. “I always assumed you had sex with your bathers,” the father says. “I know I do.” Again, the king is presented as misogynistic and patriarchal, without considering that his son may be trying to break free. He allows Akeem to go and travel for 40 days, assuming he wants to “sow his wild oats,” and that he’ll come back and marry the bride they chose for him.

As they prepare to leave, Akeem tells Semmi that he plans to find a wife during his travels. “I want a woman who will arouse my intellect as well as my loins,” Akeem says. They decide to go to New York City, specifically Queens, because he assumes there’s no better place to find a queen.

|

| Akeem is excited to be in Queens; Semmi is less than impressed. |

It’s a priority to Akeem that no one knows he’s royalty. He wants them to stay in the most “common” part of Queens, and asks the landlord to choose the “poorest” apartment for them to rent. When a woman throws garbage out of her window, Akeem exclaims, “America is great indeed–imagine a country so free, one can throw glass on the street!” Observations on wealth and ethnocentrism are also peppered throughout the film.

The two drape themselves in New York sports teams jackets and hats, and are mesmerized by a commercial for Soul Glo. Akeem goes to the barber shop (a gathering place near their apartment, where Murphy and Hall both play other parts). He gets his long princely ponytail cut off. The barber is impressed with his natural hair, and Akeem says he’s never put chemicals in it, just “juices and berries.” Later, the barber would rant and rant when Akeem asks for a Jheri curl, touting the importance of keeping hair natural. Between that and the brief rant by a white Jewish man in the barber shop (played by Murphy) that a person should be able to choose his own name, important facets of African American history and identity are touched upon in the barber shop (which were often official gathering places during the civil rights movement).

After a night of meeting women of various disaster levels, Akeem and Semmi end up at a Black Awareness Week rally (specifically, the Miss Black Awareness Pageant), where Akeem immediately becomes enamored with Lisa McDowell (Shari Headley), the organizer of the rally and daughter of Cleo McDowell, who owns McDowell’s (a small fast food restaurant that borrows a lot from McDonald’s). She takes the microphone to stress the importance of individual expression (somewhat belittling the pageant, even if tongue in cheek) and asks the crowd to donate to a park for children to be able to express themselves. Akeem puts a giant wad of cash in the collection basket, and the next morning, Akeem and Semmi show up at McDowell’s to get jobs.

Akeem learns how to mop, and tries to flirt with Lisa, who is hard at work on a computer in her office. Akeem clearly, and immediately, values a woman with a sense of identity and purpose beyond serving a man.

Soul Glo heir Darryl (Eriq La Salle) is Lisa’s boyfriend, and the audience immediately knows he’s an ass–he puts no money in the collection basket (and lets Lisa think he was responsible for the large donation), he buddies up to Cleo and is condescending toward Lisa. If Akeem was more like Darryl, or even Semmi, his life would have been easier–he could have simply married his chosen wife and followed in the footsteps of what’s expected of powerful, wealthy men because “tradition.” The film presents these men to be critical of how patriarchy works–or doesn’t–within a culture (or cultures).

The film continues to present these entrenched ideas: “Is this an American girl? Go through her poppa… Get in good with the father, you’re home free,” the barber tells Akeem. “I don’t know how it is in Africa, but here rich guys get all the chicks,” says a McDowell’s clerk (played by Louie Anderson).

Akeem goes along to a basketball game with Lisa, Darryl and Lisa’s sister, Patrice, who is presented comically as shallow and very interested in sexual conquests and wealthy men, unlike the noble Lisa. Can’t have a romantic comedy without a little virgin/whore dichotomy action!

Darryl makes disparaging remarks to Akeem about being from Africa, commenting about how it must be weird to be wearing clothes, and asking if they play games like catch the monkey. Earlier, the landlord says to Akeem and Semmi that the apartments have an insect problem, “but you boys are from Africa so you’re probably used to that.” When characters reinforce the African savage stereotype, it’s clear that these characters are not good.

|

| Akeem is a good friend to Lisa when Darryl is forceful and misogynistic. |

And when characters act like women are to be subservient sexual objects without their own identities, it’s also clear that they are in the wrong. From the king’s bawdy suggestions and adherence to the tradition of submissive, chosen wives, to Darryl pressuring Lisa to quit her job (“My lady doesn’t have to work”) or announcing their engagement without asking her if she wants to marry him (he went through her father, after all), men who don’t respect women are not the good guys–they are the ones who need to change.

When Akeem stands up to a robber at McDowell’s (Samuel L. Jackson doing one of the things he does best–wielding a gun and saying “fucker” as many times as possible), Darryl makes light of the fact that he hid, and suggested that Akeem knew those moves from fighting “lions and tigers and shit.” He then says, “They might not admit it, but they [women] all want a man to take charge–to tell them what to do.” Akeem smiles at him, but knows that’s not true.

Lisa’s affection for Akeem grows when he quotes Nietzsche and when he is a thoughtful, sensitive listener when she’s angry that Darryl steamrolls their engagement, which she refuses.

“I’m fine,” she assures Akeem. “I’m just not going to be pressured into marriage by Darryl, my father, anybody.” Akeem says he understands, and that he doesn’t think anyone should get married out of obligation.

When they go out to dinner, Lisa says how nice it is to be with a man who knows how to express himself and she insists on taking the paycheck. Lisa’s attraction to these stereotypically not-masculine traits serves as a reminder that there is value to these qualities in both men and women.

|

| Lisa is smart and independent, qualities Akeem isn’t supposed to want. |

Cleo pressures Lisa to marry Darryl as he sees her drifting toward Akeem. “You only like him because he’s rich,” Lisa says. Cleo–who has positioned himself as the ultimate bootstraps-pulling American dream–tells her that he just doesn’t want her to struggle like he and her mother did.

Akeem’s charade begins to unravel as his family arrives in Queens via motorcade. Cleo is elated that Akeem is actually a prince; Lisa is devastated that he’d lied to her (and the fact that the king told her Akeem was only sowing his “royal oats” in America before he got married).

Akeem chases after Lisa, and begs her to marry him. He offers to renounce his throne, and explains that he only wanted someone to fall in love with him for who he is, not for his money or royalty. She hesitates, but refuses, and runs off.

Queen Aeoleon (Akeem’s mother, played by Madge Sinclair) begins pushing back against her husband, challenging him about how he knows Akeem doesn’t love Lisa, and that the arranged marriage is a “stupid tradition.” “Who am I to change it?” asks the king. “I thought you were the king,” she says.

Back in Zamunda, a royal wedding has begun, and Akeem is waiting for his bride, looking resigned and sad. A bride in an enormous pink dress and veil walks down the aisle. When he lifts the veil from her face, Lisa’s face is smiling at him. He looks elated, and his parents are smiling (the queen’s logic reigned), and Cleo steps up to join the king and queen.

|

| Akeem is surprised that Lisa is under the veil. |

As they ride off in a carriage among a crowd of cheering partygoers, Lisa asks if she would have really given all of this up for her. “Of course,” Akeem responds. “If you like, we can give it all up now.” She says, “Nah,” and they laugh, and live, I’m sure, happily ever after.

The plot is pretty predictable. Female subservience is challenged, but standards of female beauty aren’t. The characters aren’t remarkably complex, but their motives are clear and almost always understandable. That said, this is a romantic comedy. I don’t mean to demean the genre as a whole, but I think it’s safe to say most blockbuster romantic comedies are pretty damn problematic, so to have a romantic comedy that subverts the notion of valuing wives who are simply beautiful and submissive while featuring a predominantly black cast and depicting Africa positively, I’d say that’s a win.

|

| Lisa is OK with her royal title. |

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.

Love this.