This guest post by Julia Patt appears as part of our theme week on Violent Women.

“Hell is a teenage girl.” So Anita “Needy” Lesnicki (Amanda Seyfried) informs us in the opening voiceover monologue of Jennifer’s Body.

At first glance, it’s kind of a throwaway tagline sort of quote reminiscent of Mean Girls or Heathers. Teenage girls are the worst—they might even be evil, but just “high school evil,” to borrow another line from Diablo Cody’s highly quotable script for Jennifer’s Body. But we should note that the line isn’t, “The devil is a teenage girl” or “Teenage girls are demons.” Rather: “Hell is a teenage girl.” Which suggests not only evil, but also suffering. Teenage girls may make other people suffer but, more than that, they suffer profoundly themselves. And although Needy’s flashback indicates she’s thinking about her friend, Jennifer Check (Megan Fox), when she makes this observation, her present tense delivery and its placement in the script at least suggest the possibility that she’s also thinking about herself.

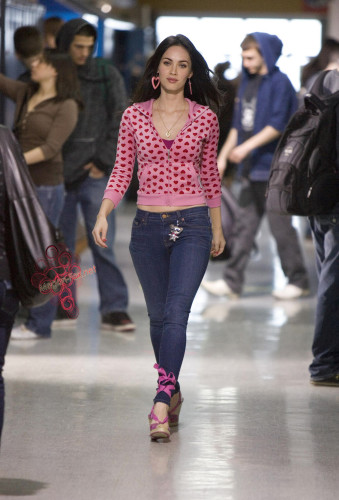

Megan Fox as Jennifer Check

Jennifer’s Body comes from a long, proud tradition of possession movies about women, particularly young women, from The Exorcist to Paranormal Activity. But given the conspicuous absence of old priests and young priests—indeed any mention of exorcism at all—the film’s closest analogue is, I’d argue, its pre-9/11 sister movie and cult werewolf flick, Ginger Snaps. Thematically, Jennifer’s Body mirrors Ginger Snaps in many respects: the disruption of suburban or small town life, the intersection between female sexuality and violence, the close relationship between two teen girls at the films’ centers, and—perhaps most strikingly—the contagious nature of violence in women.

Look familiar?

Ginger Snaps takes place in a Canadian suburb called Bailey Downs, where a mysterious creature, the Beast of Bailey Downs, has been picking off house pets, mainly dogs. The movie begins with the discovery of another such canine victim, but the attacks happen with enough frequency that, aside from the hysterical owner, no one bats an eye at this newest fatality. Other than the beast, the community is distressingly normal to the film’s two protagonists, Brigitte (Emily Perkins) and Ginger (Katharine Isabelle) Fitzgerald, who as children vowed to be “out by 16 or dead in this scene, but together forever.” Ginger at least appears to have opted for the latter option, as the sisters’ first scene together is a lengthy discussion and staging of various forms of suicide, which they put together as a photo slideshow for class. Although Ginger hails suicide as the “ultimate fuck you,” Brigitte is markedly less certain, worrying aloud that people will just laugh at her in her casket, her death having changed nothing.

Excellent show-and-tell project

There is of course much about the Fitzgerald sisters’ plan that conforms to the status quo. Suicide is an undeniably violent act, but it’s a self-directed violence, physically harming only the sisters and expected of women whom society views as predominantly nonviolent towards others. Given the abandonment of “out by 16,” it seems evident, too, that the sisters have succumbed to what they believe to be an inalterable, futile situation. They have no power to truly challenge the structures that make them so miserable. That is, until the Beast of Bailey Downs, a werewolf, attacks Ginger and she begins to change.

That the change happens simultaneously with puberty—her first menstrual cycle literally begins on the night she’s bitten—only heightens the sense of power Ginger now feels. Although still a weird Fitzgerald sister, her sexual appeal only increases throughout the movie until she fully transforms. This on its own is insufficient to manifest as a disruption. Ginger’s male classmates are only too happy to view her as a sexual object, albeit a slightly unsettling one. Even her confidence is unthreatening as long as it is confined to the context of their own desires. No, the difficulty is that Ginger remains unsatisfied and is no longer content to be so.

Unfortunately, nothing in this aisle for lycanthropy

In Jennifer’s Body, Needy and Jennifer play somewhat different roles in an otherwise familiar setting. Rural Devil’s Kettle, named for an unusual waterfall, may differ geographically from Bailey Downs but the sense of limitation and confinement remains. At the beginning of the film, Jennifer urges Needy to come to a concert with her because the band, Low Shoulder, is from the city. Her desire to leave Devil’s Kettle is evident in her enthusiasm, a fact Needy appears to wistfully recognize as they watch Low Shoulder perform at the local drinking hole. But Jennifer is no social outcast in the vein of the Fitzgerald sisters. She is, as Needy unnecessarily informs us, “a babe.” And though she characterizes herself as a dork in comparison, Needy herself hardly qualifies as a weirdo. “We were our yearbook photos,” she explains in her voiceover. “Nothing more, nothing less.”

Hard to make Amanda Seyfried look “dorky” but they tried

Jennifer and Needy’s desires similarly do not disturb societal structures. Even Jennifer, extremely cognizant of her sexual powers, is ultimately unthreatening. She is not much of a party girl either, saying longingly at the bar: “I can’t wait until I’m old enough to get trashed.” In other words, she plays by the rules. And despite her assertive attitude, willingness to manipulate men, and apparent confidence, the right sort of masculinity is enough to overcome her. This is painfully evident in her interactions with Nikolai, the lead singer of Low Shoulder, who continues to fascinate her, even after he insults Jennifer and the town.

Satanists with awesome haircuts

In fact, Nikolai brutally uses Jennifer’s desire for and idealization of the outside world against her. After a fire breaks out in the bar, killing several people, she and Needy flee through the bathroom window. Outside, Nikolai finds them and leads Jennifer away to the band’s van—the last time Needy will see her alive, as the members of Low Shoulder intend to sacrifice her in exchange for their commercial success. (It’s a hard world for an indie band. They’re just all so pretty.) When Jennifer appears again, covered in blood, she is possessed by a demon—and as with Ginger, her desires can no longer be sated by ordinary means. As Devil’s Kettle becomes a place of tragedy, Jennifer transforms into an agent of gleeful destruction, lusting not for attention or boys or society dictates for a teenage girl, but rather for power, violence, and fear.

The new Jennifer doesn’t care about gender roles

Ginger comes to a similar conclusion about her longing. “I get this ache,” she confesses to Brigitte. “I thought it was for sex, but it’s to tear everything to fucking pieces.” This conflation between sex and violence is hardly unique to Ginger Snaps or Jennifer’s Body, but the emphasis on female sexuality and female power subvert our expectations in the violent scenes. Nor are these neat, orderly killings—both Ginger and Jennifer tear open and partially consume their victims. These films are bloody and that blood belongs almost exclusively to men. Of the two, Ginger is much more erratic in her selection of victims, striking out mostly at male authority figures as they threaten her. This is fitting for her affliction and the gradual nature of her change, which, in an unusual twist on the werewolf trope, happens over the course of the month until the full moon instead of all in one night.

Jennifer, conversely, makes a full transition to her new undead, possessed state of being although her feeding patterns notably also occur on a monthly schedule as the life forces of her victims wane. As a hungry demon, as Needy points out, Jennifer appears remarkably like a woman in the throws of PMS: “She gets weak and cranky and ugly.” Being full, Jennifer explains, is an incredible high—and she’s basically indestructible. It’s no wonder that each month she seduces and consumes another boy after the juice from the last runs out. Externally, this does not manifest as a large behavioral shift. Jennifer is flirty, appealing, and deliberately submissive as she lures in her next meal. The difference is she no longer figuratively attains her sense of self-worth from her conquests—they are literally making her more beautiful and powerful.

Confidence is terrifying

We can understand why Ginger and Jennifer become so insatiable and simultaneously why their hunger appears so monstrous in the context of patriarchal society. Their love of killing makes them a serious threat. It’s the full realization of their powers and the traditional means by which they might be subdued—control over their self-image, social standing or physical wellbeing—no longer work. For the first time in their lives, both are completely uninhibited. They are free to want. There is something almost laudable about their transformations, too; they’ve gone from almost certain victims to powerful killers. And it’s all the more telling that we can characterize both films as macabre comedies as well as horror flicks; they are often as funny as they are frightening and their delight in the upending of social convention is palpable.

But it is the way of horror that normalcy often reasserts itself and the monster is destroyed. In the case of both Ginger Snaps and Jennifer’s Body, the agent of that destruction is not a man but another teenage girl—and not just any girl, but a literal or metaphorical sister.

Inseparable…until one of us gets bitten by a werewolf

Ginger’s relationship with her sister remains the only reliable element in her life, although her encroaching transformation certainly strains it, as she abandons, threatens, and ignores her at various turns. It’s clear from the outset that their relationship has always been one of distinct inequality with Ginger as the leader and Brigitte the follower. Brigitte, who grows more assertive as the story progresses, is determined to find a cure for her sister’s condition and teams up with local drug dealer and apparent lycanthrope enthusiast Sam. However, this new alliance irritates Ginger, who as they go to consult with him drolly remarks, “Romeo, Romeo, where for art thou, Romeo?” In fact, although there is real affection at the heart of their relationship, Ginger is undeniably possessive and jealous regarding Brigitte, accusing even the school’s elderly janitor of checking out her sister and then killing him in a fit of werewolf-induced rage. Neither is it accidental that Sam becomes her intended target, as she first attempts to seduce him and then attacks him when that fails. However, she does not target Brigitte until the very end of the film, at which point Brigitte resigns herself to killing Ginger in self-defense.

There are striking similarities in the relationship between Needy and Jennifer. Jennifer is often possessive and controlling of the weaker-willed and aptly named Needy. But they genuinely care for one another, as Needy observes, because, “Sandbox love never dies.” Despite her altered state, Jennifer avoids harming her friend, even when the demon inside her would clearly be glad to rip her to pieces, too. Instead, Jennifer settles for consuming the boys around Needy, including her goth friend, Colin, and her boyfriend, Chip. This last murder drives Needy to finally take action against Jennifer and the two exchange barbed insults in two confrontations that eventually result in Jennifer’s death. Needy flatly exposes Jennifer’s insecurities, revealing a dynamic that has subtly developed over the course of the film: Needy is the stronger and more capable of the two.

Jennifer confides in Needy

It is tempting to read these two endings as a reassertion of patriarchal values in the vein of conservative horror: the well-behaved, sensible girl saves the day and survives to tell the tale while the sex-crazed, uninhibited female monster is destroyed. This is accurate but for two facts: the tragedy of our two heroines and the contagion of violence. Brigitte and Needy are devastated by what they have to do, both visibly mourning the women they loved. For them, these moments are personal, not political. It’s worth asking if they would have intervened at all had Ginger and Jennifer ranged farther afield. Both look for other solutions; both permit at least one person to die despite what they know; both keep the confidences given to them. At the end of Ginger Snaps, Brigitte leans over the body of her transformed sister and sobs; having killed Jennifer, Needy is broken, bitter, and changed, spending her days in a mental health institution for criminals. Neither looks much like a heroine of the patriarchy; neither returns to the strictures of society.

Not so Needy anymore

And both are marked in more significant ways. Brigitte deliberately infects herself to gain Ginger’s cooperation. Jennifer scratches Needy as they struggle, thus communicating some of her demonic powers to her friend, a fact Needy reveals at the end of the film as she levitates out of solitary confinement and escapes. Although Ginger Snaps 2: Unleashed show us more of Brigitte’s fate—which also involves institutionalization—it’s unclear at the end of the first movie what the outcome of her infection will be. Jennifer’s Body gives us rather more, because Needy has one thing on her mind: revenge. The closing credits of the film reveal the gruesome deaths of Low Shoulder, and security footage shows Needy strolling towards their hotel room, her intent unmistakable.

Brigitte and Needy’s reactions remind us what we might forget over the course of these films: both Ginger and Jennifer are victims. They did not intentionally become what they are. But their survival makes them strong, even as it changes them in other more horrific ways. Those changes and that power are, the films seem to suggest, communicable. And despite their destruction, something of what they’ve gained persists in the women who love them and survive. Although the immediate threat may have passed, the possibility for further violence lingers.

Julia Patt is a writer from Maryland. She also edits 7×20, a journal of twitter literature, and is a regular contributor to VProud.tv and tatestreet.org. Follow her on twitter: https://twitter.com/chidorme