This guest post by Erin Blackwell appears as part of our theme week on Bad Mothers.

L’affaire Le Roux, or more vulgarly, the Leroux Affair, is a real court case involving a young heiress on the French Riviera, whose body never turned up, whose inheritance was absorbed by her lawyer-lover who didn’t love her, whose mother ran a sumptuous casino the Mafia plucked from her grasp with the aid of said lawyer-lover, a case that is still working its way through the courts today, 38 years after the young heiress vanished. Whatever else this affair might signify, say, to legal minds and the involved parties, it has served to inspire a movie that is very fabulous for the first 90 minutes of its 116 total run time.

In the Name of My Daughter premiered at Cannes 2014 out of competition, one month after Maurice Angelet was convicted for the second time to 20 years in prison. That same day, he launched another appeal. Frankly, I can’t keep up with this case, which keeps insinuating itself into my thoughts about the film, which is now in certain U.S. cities still able to sustain an art house. In the Name of My Daughter, directed by André Techiné, is an intimate melodrama wrought from sensational facts, starring Catherine Deneuve as a platinum blonde grande dame and Adèle Haenel as her wide-eyed and wild-hearted daughter. These two characters’ inability to see each other as anything other than personal property emerges as the compelling dramatic engine of unfolding events involving far more sinister agents, who eventually exploit the fissure in the mother-daughter bond.

Money changes everything? Money ruins everything. Especially in families. Especially when one generation does all the work and the next does all the spending. It is, of course, in the nature of a child to receive love, shelter, warmth, food, care, education, advice, protection, but in the presence of wealth, children sometimes prefer to take the money and elude the smothering, or the well-upholstered neglect or abuse. This syndrome is the crux of In the Name, when the daughter demands her small fortune in shares left by her dead dad, the immediate sale of which would compromise her mother’s ability to stay in business.

The father’s name is never spoken, nor his memory invoked. No incidental photos on a gilt rococo side table in the centuries-old Le Roux villa on the hill overlooking the drop-dead view of the Bay of Angels. And yet he reaches beyond the grave to separate the mother from the daughter by establishing the latter’s legal right to her fair share in the family business. This is the stuff of melodrama, and the French invented that genre after the Revolution to cover the sordid money-based family squabbles of the bourgeoisie. There’s no melodrama without a money angle, ever a reliable motive for murder.

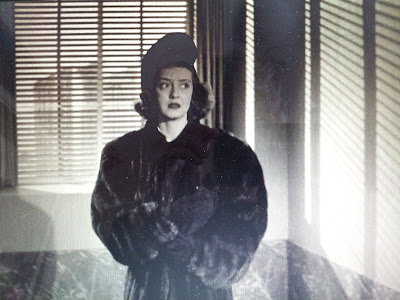

Deneuve isn’t just Mom, or Maman, she’s the chic proprietress of one of the classiest casinos in Nice, le Palais de la Méditerrannée. All tarted up with heavy eyeliner and lipstick, platinum hair in a French twist, wearing clothes Imelda Marcos would fancy that look like shot-silk Chanel suits on acid, Deneuve is a vision of old, stolid, corrupt, bourgeois, money-grubbing glamour as it can only exist on the Côte d’Azur (Azure Coast), where the sun smiles on the blue Mediterranean, palm trees dance in the breeze, and the Mafia and other lesser-known brands of evil are eager to get in on the game. Not unlike Southern California, birthplace of Noir.

When we look at Deneuve’s face, we’re still looking for the young or younger face. That’s how it is with people we’ve “known” for years, and loved. The mother still sees the child, even as she must deal with the young woman. The daughter still yearns for the mother’s affection and attention, which she used to wallow in, or fail miserably to attract. The mother would like to move past dutiful child-rearing to a relationship in which she, too, is a person to be cherished and supported. So, fighting for the life of her casino and its 350 loyal employees, against an interloping crime syndicate, she asks her daughter to be patient.

Haenel as Agnès gives a performance impossible to imagine in a Hollywood film. She goes for broke. She tests the limits of her own vulnerability and our ability to watch her spiral out-of-control like a weepy drunk at a party. She bares all, as the tabloids like to say, which is why we love tabloids. Being French, what she bares is the soul of a Romantic, an open heart, a trusting nature, and a bottomless pit of emotional chaos. Her mother doesn’t mind her being a bit of a mess, and that’s a catastrophe for the child, should she ever fall prey to a cynic, a non-believer in romance, a soulless opportunist, someone in it for the money. Oops. I gave away the plot.

Haenel dances an African solo sans bra, swims, smokes, and stares with an abandon utterly opposite to the mother’s rigorous, staid, encrusted rituals. And yet, Deneuve’s eyes reveal the sophisticated depth of emotion those in the know count on the French for. Beneath their façades, their aspirations aren’t dissimilar, but Mom, like Mildred Pierce, does have a business to run, and Agnès, like Vita, doesn’t give a shit.

The original French title, L’homme qu’on aimait trop, or The Man We Loved Too Much, is a saucy wink towards real-life sleazy lawyer Maurice Agnelet, the third angle in the triangle. Agnelet is played by Guillaume Canet as your typical sociopathic control freak, who sucks up to Madame Le Roux because she is his only paying client, she pays well, and he figures he can parlay the widow’s quasi-maternal fondness for him into the professional jackpot of his dreams: a real job paying a real salary, affording him real power over his life and allowing him unlimited motorcycles, women, and prestige among those very fussy, old-money types who haunt the casino.

The American title, In the Name of My Daughter, refers to the fact that real-life Renée Le Roux dedicated her later years to proving Angelet guilty of her daughter’s murder. Without a body, that’s tricky. And one of his girlfriends gave him an alibi, so he served a year in prison and was released. Years later, that girlfriend changed her mind, said she’d lied, he wasn’t with her in Geneva when Agnès, after a well-documented suicide attempt, disappeared. Agnelet was tried again in 2006 and acquitted. In 2007, he was condemned to 20 years. In 2013, the European Court intervened to overturn the verdict and set him free. Last year, his own son testified against him, he was again given 20 years, a verdict he immediately appealed, a month before the film premiered at Cannes. You can see why Techiné had trouble closing his narrative. Too bad I wasn’t there to persuade him his rendering of the triangle is more compelling as a psychological mystery than any mere legal wrangling.

The American title, In the Name of my Daughter, suggests U.S. distributors hope to sell this mother-daughter-lawyer triangle as “a woman’s picture,” even though that’s a hard sell in this hard country. Variety‘s manly reviewer complained the audience is denied the spectacle of grande dame Renée Le Roux being whacked on the head by a thug, having to settle instead for Deneuve’s restrained account at a swanky press conference in her casino. Why go to the movies, thinks the red-blooded American male, if I can’t see a woman being attacked? All I can say is, thank God for the French.

The first 90 minutes make a splendid neo-noir built on a classic triangle, like something out of Liaisons Dangereuses. The mother and the lawyer both have hard heads, the daughter is the weak link. When the lawyer tries to push Maman around, she shoves him back in his place. Suddenly the daughter’s unresolved Electra complex, her past-due-date adolescent rebellion, makes her vulnerable to the lawyer’s machinations. The intrigue is spellbinding. Then Agnès disappears. No more triangle. Instead of ending the film here, director André Téchiné wanders into the vagaries of a complex legal battle and the camp value of facial prosthetics and wigs. Bad idea.

In the Name of My Daughter, a terrible title, is based on Renée Le Roux’s memoir, A Woman Against the Mafia, about how her fight to stay in business resulted in the death of her daughter. Techiné, who co-wrote the script, makes not the Mafia, but the daughter’s tragic flaw the heart of the movie. Adèle Haenel plays Agnès as a slapdash, brooding, needy, watery-green-eyed tomboy-siren whose bourgeois bubble has ill-equipped her to deal with an arriviste rat like Agnelet. We watch her swim, like Alice swims in her own tears, while Maurice bides his time on the sand, and never was there a more astute rendering of the battle of the genders, or the Romantic vs. the Mercenary, or the spoiled hippie child vs. the sociopath.

Adèle Haenel’s Agnès reminded me of François Truffaut’s Adèle H., incarnated by Isabel Adjani as a woman shamelessly in love, who similarly loses first her self-respect and then her reason. That 1975 film, also based on real life, came two years before Agnès vanished in 1977. It’s entirely possible the real Agnès Le Roux watched Adèle H. and recognized that doomed Romantic story as her own. Bizarre, bizarre, that an actress named Adèle H. should incarnate Agnès Le Roux.

The fabled Côte d’Azur is a different country from the rest of France, a stone’s throw from Monaco, where the high-rollers have their empty apartments, and a short hop by motorbike to a Swiss bank, as the film splendidly demonstrates. It’s a real place and this was a real news story before it became a film. Apart from suffering narrative decline at minute 91, Techiné’s film is a riveting portrait of an homme fatal, a creature we don’t see enough of onscreen. Deneuve’s beauty isn’t right for the character, and it’s a distraction, but a fascinating one so who cares, and it does work to establish the daughter’s hatred of the mother, who is visibly everything she is not. I was regretting the fillers in her cheeks and rooting for her muscles’ ability to still deliver recognizable human expressions. The muscles do pretty well. The eyes are where it’s happening, however. Lively and liquid, Deneuve’s orbs register the pains of a heart that has gambled on a daughter and lost.

Erin Blackwell is a consulting astrologer who was raised to regard movies as a form of worship. She blogs at venus11house.