Outlander and A Modern Man by Alize Emme

“What is her power over you?” Randall chides Jamie during his psychological torture. As manly as Jamie likens to be, he long ago surrendered himself to Claire’s power over him. In his deteriorated state, only a woman can heal this broken man. While Jamie’s brokenness is wholly justifiable, his extremist way of thinking shows his ideas of masculinity will need to continue to evolve if he wants to fully regain his soul.

Mad Max: Fury Road Allows Audiences to Both Enjoy and Problematize Hypermasculinity by Elizabeth King

As the evil dictator of the territory he occupies in a post-apocalyptic world, he demands more and more gasoline (which is in rare supply), while withholding water from his starved and sickly citizens. He also has a collection of women that he imprisons and uses for breeding purposes. In this single character we see some of the worst aspects of rampant hyper-masculinity condensed into one truly horrifying man.

Masculinity and the Queer Male: There’s Nowt So Queer as Folk by Rowan Ellis

Yet this very concept of shaming queer men for their sexuality while society is praising straight men for their sexual conquests as a key element of “successful” masculinity demonstrates the way homophobia intersects with a devaluing of the feminine.

Strong in the Real Way: Steven Universe and the Shape of Masculinity to Come by Ashley Gallagher

Steven, the title character, isn’t the troublemaking, reckless, pain-in-the-butt Boy-with-a-capital-B I feared I’d have to watch around to get to the powerful women and loving queer folk I really wanted to see. He’s unreserved, adventurous, and confident – all good traits that are fairly typical for boy leads in kids’ shows – but he is also affectionate, selfless, very prone to crying, and just plain effin’ adorable.

The Three Questions That Divide Breaking Bad Fans and What They Tell Us About Masculinity by Katherine Murray

Breaking Bad is one of those well-written, well-acted shows that somehow inspires people to scream at each other in CAPSLOCK. The debate about Walter White and his wife and their drug-trade boils down to your answers to three deceptively simple questions that act as a rorschach test on masculinity in American culture.

The Conflicting Masculinities of Frank and Claire in House of Cards by Tilly Grove

It is this point at which things significantly begin to shift in Frank and Claire’s relationship. This entire situation, which occurred in a succession of embarrassments for Frank, clearly served as a challenge to his dominance and an infringement on his masculinity, especially coming from his wife. For Claire, meanwhile, it is evident that while Frank is fighting desperately to enforce his masculinity and remain in power, she has lost all of hers.

The Blind (Drunk) Leading the Blind (Drunk): Masculinities and Friendship in Edgar Wright’s Three Flavours Cornetto Trilogy by Tessa Racked

Two distinct masculinities pull the Trilogy’s heroes in different directions. Given Wright’s frequent use of pop culture references, I’ve opted to borrow Dungeons and Dragons’ terminology and describe these extremes as lawful and chaotic. Lawful masculinity is characterized by competency and order; it is the hallmark of the responsible (but rigid) adult. Chaotic masculinity is characterized by hedonism and anti-authoritarianism, usually embodied in the series by characters in a state of adolescence (whether age-appropriate or not).

A Fragile Masculinity: Genderswapping Male Characters by Alyssa Franke

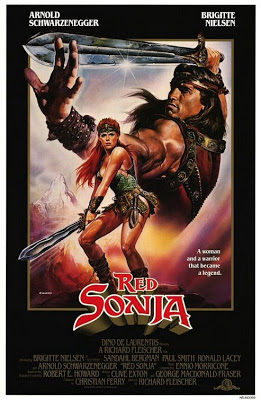

Part of this belief comes from the assumption that casting women in these roles is always an attempt to tone down the masculine-coded characteristics associated with these characters. Vaguely omnipotent feminist forces are conspiring to emasculate hyper-masculine characters by recasting them as women, so the argument goes.

I Think We Need a Bigger Metaphor: Men and Masculinity in Jaws by Julia Patt

The life Brody has lived is utterly different, if not entirely sheltered. What dangers or dilemmas he’s faced in his life simply haven’t left the kind of marks Hooper and Quint bear. And their lack prevents him from engaging in any stereotypical masculine posturing. He is, by that criteria anyway, untested.

Female Masculinity and Gender Neutrality in Dexter by Cameron Airen

Knowing that his son had and would continue to kill, Harry taught him to follow a strict code that only allowed Dexter to kill “bad” people. Instead of being chaotic, spontaneous, and killing out of pure rage, Dexter developed a more methodical approach. He is a neat monster who creates a pristine kill room with everything clean, tidy and in its place. All of this could be seen as a more feminine kind of control.

The Complex Masculinity of Outlander’s Jamie Fraser by Carly Lane

It’s a surprising twist on the trope. Jamie is undoubtedly a force of man to be reckoned with, though the fact that he is a virgin and thus relatively inexperienced in terms of sex when he encounters Claire – the older, more experienced woman – attributes some unexpected “feminine” qualities to his character.

Mad Men: Masculinity and the Don Draper Image by Caroline Madden

Upon viewing the series after knowing the show’s finale, we see that the Don Draper arc reflects a small change in gender perspectives during that era. The Don of Season 1 would never act as the Don in the Season 7 finale. We see that Mad Men was all about shattering the hyper-masculine Don Draper mythos that he built and trapped himself within.

How Avatar: The Last Airbender Demonstrates a More Inclusive Masculinity by Aaron Radney

All of them, even those that have more traditional male expressions than the others, end up rejecting more toxic expressions of masculinity.

Misogyny Demons and Wesley’s Tortured Masculinity in Joss Whedon’s Angel by Stephanie Brown

Not only does the characterization of this violent misogyny as “primordial” imply that violence toward women is the natural state of men, it also implies that gender itself is an essential and natural state of being. Men are men and women are women. In a universe that generally operates in gray areas, such a distinction is uncharacteristically black and white.

Tough Guise 2: Disrupting Violent Masculinity One Documentary at a Time by Colleen Clemens

Narrator Jackson Katz uses visuals and film clips to argue that such a view of masculinity is creating a crisis in young boys as they grow up being made to feel that violence=agency and that rape is just fine because you should get what you want—and if the answer is “no,” then you just take it.

Off the Fury Road and Without a Map: Masculine Portrayal in the New Mad Max by Zev Chevat

Wrapped in a hypermasculine Trojan Horse of violence and war custom is a heady lesson about the dangers of ceding to those expectations, and about the road away from them and toward something like redemption. Here is a film where women are shown to be men’s combative equals. Even more so, it is a film where the only way the men can escape their own oppression is to join up with, and occasionally defer to, these women.

Negotiated Identities and Gray Oppositions in Ridley’s American Crime by Sean Weaver

With that said, even the traditional gender binary is flipped on its head—the women of the show uphold the patriarchal system that controls them, while the men are often portrayed as effeminate and oppressed by the same system that is supposed to give them power. Yes. Take a second while you process that.

Masculinity in Game of Thrones: More Than Fairytale Tropes by Jess Sanders

Boys are judged on their ability to swing a sword or work a trade, criticised for showing weakness, and taught to grow up hard and cold. Doesn’t sound unfamiliar, does it? Masculinity is praised in Westerosi society, as it is in our own.

Bigelow’s Boys: Martial Masculinity in The Hurt Locker by Rachael Johnson

The movie also, however, offers ideological and anthropological readings of masculinity which are, arguably, a little more complicated. Bigelow appears to have a deep interest in, and respect for, martial masculinity.

Moving Away From the Anti-Hero: What It Means to Be a Man in Better Call Saul by Becky Kukla

Slippin’ Jimmy was to James McGill what Heisenberg was to Walter White–a hyper-masculine alter-ego. OK, Slippin’ Jimmy was only conning a few business men out of their Rolexes, but essentially both men created an alternative, more masculine version of themselves in order to survive and gain success.

The Loneliest Planet and the Fracturing of Masculinity by Cal Cleary

Alex is, in many ways, the ideal of the modern man: Handsome, athletic, intelligent, well-traveled, well-off financially but still environmentally sensitive, and with a romantic partner he treats as an equal. Because of this, he has no trouble shrugging off the gendered stereotypes expected of his relationship in the first half of the film. But as soon as he is given reason to doubt his own traditionally defined masculinity, it all falls apart.

Entourage: Masculinity and Male Privilege in Hollywood by Rachel Wortherly

Turtle reminds Vince that “the movie is called Aquaman, not Aquagirl.” This line is indicative of the “boys club” that continues to thrive in Hollywood. An actress’s livelihood in the industry is dependent on her co-star.

The Courage to Cry: Men and Boys’ Emotions in Naruto by Jackson Adler

However, when boys are told that “boys don’t cry” and that men should “man up,” their emotions are not respected, and they often internalize this stigma, sometimes with devastating consequences. Of course, simply crying won’t cure a condition as severe as PTSD, but men being shown that they are not “weak” for experiencing emotions and needing help will undoubtedly aid in the road to recovery.

Man Up: How VEEP Emphasizes the Value of Masculinity in Politics by Shannon Miller

Because he doesn’t display the same aggressive temperament (he’s actually rather sweet and nurturing) nor does he have a similar function as the rest of the group, his value is regularly questioned and his masculinity is nearly erased. Walsh broaches this issue in the second episode of the series, “Frozen Yoghurt,” when Egan flippantly claims that the famous bag is full of lip balm: “Everything you say to me is emasculating.” And it’s true!

Mr. Robot and the Trouble with the White Knight by Shay Revolver

This is another one of the problems that I have with White Knight syndrome. The types prone to exhibiting this behavior tend to have a lower opinion of women that than their outwardly sexist counterparts. White Knights take up the causes of the women in their lives and speak out for them, but it is usually done in a manner that seems to suggest they think that these women are incapable of speaking up for themselves.

Let’s Hear It for the Boy! Masculinity and the Monomyth by Morgan Faust

As the monomyth evolves, the question is: will it evolve to include the “everywoman” hero archetype, or will the nature of myth itself change to embrace not just the messaging of individualization, but the representation of unique stories for unique people?

looks at the 2008 election through a feminist lens and, (no surprise), focuses most on primary candidate Hillary Clinton, and later Sarah Palin. The book is, however, much more than just an analysis of the sexism these two women endured. Big Girls Don’t Cry looks at the ways in which the media itself was forced to adapt, particularly to Clinton’s historic run at the presidency. This book is an excellent, smartly written look back at gender politics in 2008. For me, it reopened wounds and ignited anger I felt during the election cycle, when I heard, time and again, painful misogynist commentary coming from our so-called liberal media. However, the book provides a kind of catharsis: if we can look back through Traister’s clear eye, maybe we — individuals and the collective — will change.

looks at the 2008 election through a feminist lens and, (no surprise), focuses most on primary candidate Hillary Clinton, and later Sarah Palin. The book is, however, much more than just an analysis of the sexism these two women endured. Big Girls Don’t Cry looks at the ways in which the media itself was forced to adapt, particularly to Clinton’s historic run at the presidency. This book is an excellent, smartly written look back at gender politics in 2008. For me, it reopened wounds and ignited anger I felt during the election cycle, when I heard, time and again, painful misogynist commentary coming from our so-called liberal media. However, the book provides a kind of catharsis: if we can look back through Traister’s clear eye, maybe we — individuals and the collective — will change.